1. The Mantua-Peschiera railway

The idea to construct a railway line between the city of Mantova and Peschiera del Garda in the Pianura Padana area was promoted by local initiatives shortly after the unification of Italy in 1861. In 1879, local engineer Giuseppe Benati led the effort with a general proposal, starting a long and debated history of financial proposals and requests for funding from the central government. The main parties involved were represented by Municipalities and Provinces affected by the railway’s route, which saw in the new infrastructure the possibility of new opportunities for developing the local economies of the Valle del Mincio (Mincio’s valley). While the local public offices advanced the discussion at the Ministry of Transport, on the other hand, public opinion asked for its realisation through the press, as testified by several articles in the local newspapers of the time.

The development of the project proposal was a lengthy process, with discussions starting in 1890. By 1905, the project Progetto di Massima per la Ferrovia Economica a scartamento ordinario Mantova-Peschiera was formally designed, driven by the aspirations of the Consorzio per la Ferrovia Mantova-Peschiera (Consortium for the Mantova-Peschiera Railway). The proposed project closely resembled the eventual construction of the line, yet no documentary evidence survives today aside from historical photographs and cadastral records. The surviving documents, including the only remaining graphical depiction, serve as a textual reference, pinpointing locations, waterways, and roadways by their original names—vital for orientation and understanding the places at that time.

In the wake of establishing the Società Anonima Ferrovia Mantova-Peschiera (Mantova-Peschiera Railway Company) in 1913, the group secured a concession from the Italian Ministry of Transport to construct and operate the railway. This agreement included a guarantee of a per-kilometer subsidy over a fifty-year period. However, the project faced setbacks, including difficulty securing funds and the outbreak of the First World War, delaying construction until 1921.

Following successive extensions, the line was completed only at the end of the 1920s and then entrusted in sub-concession to the Società Anonime Elettrovie Romagnole in 1932 with a modification of the concession pacts by the state in 1934, the year in which the line was inaugurated and activated using locomotive with steam propulsion. The activation had to wait until 1934 due to the discussion regarding the authorisation for circulation on the Mantova Sant’Antonio section owned by FS (Ferrovie dello Stato).

2. From Theory to Tracks: Stanislao Fadda’s Railway Manuals and Their Impact on the Mantova-Peschiera Branch Lines

Thanks to the concession regulations of 1879[1], not only was the Mantova-Peschiera railway constructed, but many other ferrovie secondarie (branch lines) were also developed, following processes similar to the one just described (Briano, 1977).

Almost all initiatives for constructing branch lines had local communities as their initial promoters, represented by public interest such as Municipalities and Provinces. Indeed, the legislation’s goal was to promote new lines to complete the railway network of the Italian Kingdom, proposing economical construction and operation systems for all those railways that did not have the characteristics of main lines.

While the diffusion of secondary, or more precisely, »economic« railway (branch lines) networks were spreading, on the other hand, engineering was the reference discipline for their construction. The practice was also related to the numerous railway manuals, authentic practical guides for constructing and formulating projects and related works (Purcar, 2007). This practice, common to all railway constructions and especially, as Maggi suggests (2003), for the realisation of branch lines, often referred to a series of 19th-century publications that owed much to the French contributions of the second half of the 19th century[2], to which Italy only at the turn of the two centuries managed to contribute, also becoming a technological reference, thanks mainly to the experiences gained from the construction of the Gotthard and Frejus tunnels or other ventures linked to the very rugged morphology of the Italian territories, which forced engineers to continuous experimentation (Bigatti & Canella, 2014).

One of the most exhaustive texts regarding railways is the multi-volume collection by engineer Stanislao Fadda titled Costruzione ed Esercizio delle strade Ferrate e delle Tramvie (Construction and Operation of Railways and Tramways), started in 1887 and continued until 1912, published in Turin by the Unione Tipografico Editrice (UTET). The unstudied work presents itself as a true railway encyclopedia consisting of innumerable chapters written by a dense group of experts, 8,000 pages of text with 10,000 figures and more than 900 plates (lithographs) and an album composed of 100 tables. Ing. Fadda’s work, like the manuals in general, strongly emphasises how each element contributes to the definition of the railway itself, a unitary system and architecture in which the absence of one of its elements prevents the correct functioning of the whole. Among the numerous volumes published with Fadda as leading editor, we find the one titled Ferrovie Secondarie ed Economiche (Secondary and Economic Railways), signed by Eng. Luigi Polese. Here, regulations, reference techniques, and some best practices for designing secondary railways are collected and probably taken as a reference for creating many branch lines of the national secondary network.

The manual aimed to guide the practice of engineers in applying the industrial conception, typical of the second half of the 19th century, imposing the consideration of railway initiatives among the industrial initiatives to achieve maximum profit with the minimum expense. At the same time, the promotion of the development of such enterprises was also due to the importance of railway networks in post-unification Italy, presenting the train as “the most powerful means of communication and transport known” (Polese, 1899, p. 5). Engineers were required to engage with a more entrepreneurial dimension, a necessity that the railways became carriers of. Alongside the drafting of the technical project, they, therefore, found themselves needing to take into account economic issues, that is, on the one hand, the expenses to be faced in their various articulations, which had to include everything from the costs required for facilities to reimbursements for expropriations to landowners, and on the other, the profits that could reasonably be expected from the initiative. The choice of one route over another, as well as the option for an alternative technological solution, weighed on the costs of the line and, in the long term, guided and influenced its design.

Within this logic, perhaps it is the branch lines, such as the Mantova-Peschiera, called »economic«, that best embody this industrial ideal since they were “intended to serve less significant centres in terms of population and production, must shed the characteristic imprint of the major lines, and consequently, an economy in operating expenses must necessarily be imposed given the very limited traffic and the modest benefits that can be expected from their operation” (Polese, 1899, p. 2).

Their economic nature promotes their development, especially in the more inland areas of the peninsula, convincing everyone “of the necessity and convenience of adopting them where the peculiar conditions of the localities impose them, as they perfectly meet the true and real needs of the small industrial and commercial centres”, also emphasising the “public service character” (Polese, 1899, p. 4) that these railways had.

The name Ferrovie Secondarie (branch lines) pertains to a classification of railways we find already at the end of the 19th century, inspired by foreign manuals that Polese recalls in his publication (1899). Based on this distinction, the railways were therefore identifiable as:

Primarie (Main Lines): «those that are necessary so that no part of the State’s territory is placed outside the greater radius of action of a railway» (Polese, 1899, p. 8)

Secondarie (Branch-railways): «those that, branching off from a main line, connect the greater radius to the lesser, and bring, under the direct action of a primary line, the countries that only felt the indirect action» (Polese, 1899, p. 8).

Locali (Short Traffic Railways): «those that, detaching from a primary or a secondary line, facilitate transport only within the smaller circle of the line from which they branch off» (Polese, 1899, p. 8).

3.»Opere d’Arte«: Living Spaces

In the volume written by Engineer Polese for the series edited by Engineer Fadda, it is interesting to note how railway facilities are referred to as Opere d’Arte (Piece of Art) (Polese, 1899, p. 13). From a technical point of view, the track and all its components are part of the infrastruttura (infrastructure) as they are necessary for the roadbed. At the same time, everything related to the operation of the line is indicated as soprastruttura (railway facilities), and it is presumed that it may change over time (Polese, 1899, p. 94). The economic nature of the branch lines, as repeatedly mentioned, requires excellent optimisation of the railway service and involves elements of the railway facilities to offer an economy in which the expenses of realisation and management are reduced to a minimum. However, the term Opere d’Arte clarifies that these elements should also be considered differently from those pertaining to the infrastructure, perhaps because they are tied to aspects not exclusively technical that involve other functions, such as that of private and public places.

Nerve centres of such facilities were the stations, with their small freight yards, often reduced to simple loading and unloading platforms, if not to a single track, from which goods could be unloaded and loaded onto ox-drawn carts. In addition to stations, along the route, there were small stops serving hamlets scattered in the countryside and crossing keeper’s houses for the control of intersections with vehicular roads and fundamental to ensure the maintenance of the line (Fadda, 1889–1912, p. 1).

Geometric chronotopes that leave a footprint in the place and enable us to identify “the time of nature and the time of human biology” (García Nofuentes & Martinez Ramos e Iruela, 2022, p. 2). Such architectures propose a recognisable order, “offering a precise explanation of the differences between the circumstantial factors of its creation and its essential issues.” (García Nofuentes & Martinez Ramos e Iruela, 2022, p. 3).

The line was populated not only by Opere d’Arte but by those who inhabited them. Cassola well describes many lives tied to work in his book “Ferrovia Locale” (Local Railway), where the multiple stories of the protagonists share the railway as a place of living, work, and everyday life (Cassola, 1968). The characters of specific architectures, because this is what it is about, although standardised as far as all lines pertaining to the Main Lines were concerned, became surprisingly varied regarding the concession railways, thanks to the great freedom the companies had in realising the granted projects. Their economic nature only pertains to exceptional pieces of art. Still, they adopt the same systems of ordinary railways with differences mainly in the simplicity of details “or rather, in the absolute lack of everything that smacks of decorative or monumental things from which the works of art of the secondary railways must be exempt” (Polese, 1899, p. 113).

A scarcity of resources contributes to adopting collective intelligence, “which represents one of the values of vernacular architecture” (Rosaleny-Gamón, 2022, p. 3).

Despite the call for simplicity in architecture, engineers enriched the impeccable functional machine with moderate decorative features often taken from residential building manuals to soften the buildings by combining the function of a public building with that of a residential one (Assirelli, 1992). Indeed, until not many years ago, railway architectures were designed to house entire family units whose members, as Cassola still reminds us, actively participated in the life of the lines. Thus, the station master, the crossing keeper, the labourer, the deputy, and all those who animated those places, often lost in the territories of our Peninsula, became part of the social life of the villages and the countryside, figures as characteristic as the teacher and the priest. Moreover, railway architecture’s»figurative« features were meant to indicate cultural and social significance and emphasise their territorial impact (Colleanza, 2007, p. 9). In line with the established role, the figurative features were increasingly simplified, leading to the signal cabin, one of the smallest elements among railway architectures. A perception of the collective imaginary that perished due to its disappearing but also to the changes in the landscape of the environment (Rosaleny-Gamón, 2022, p. 3).

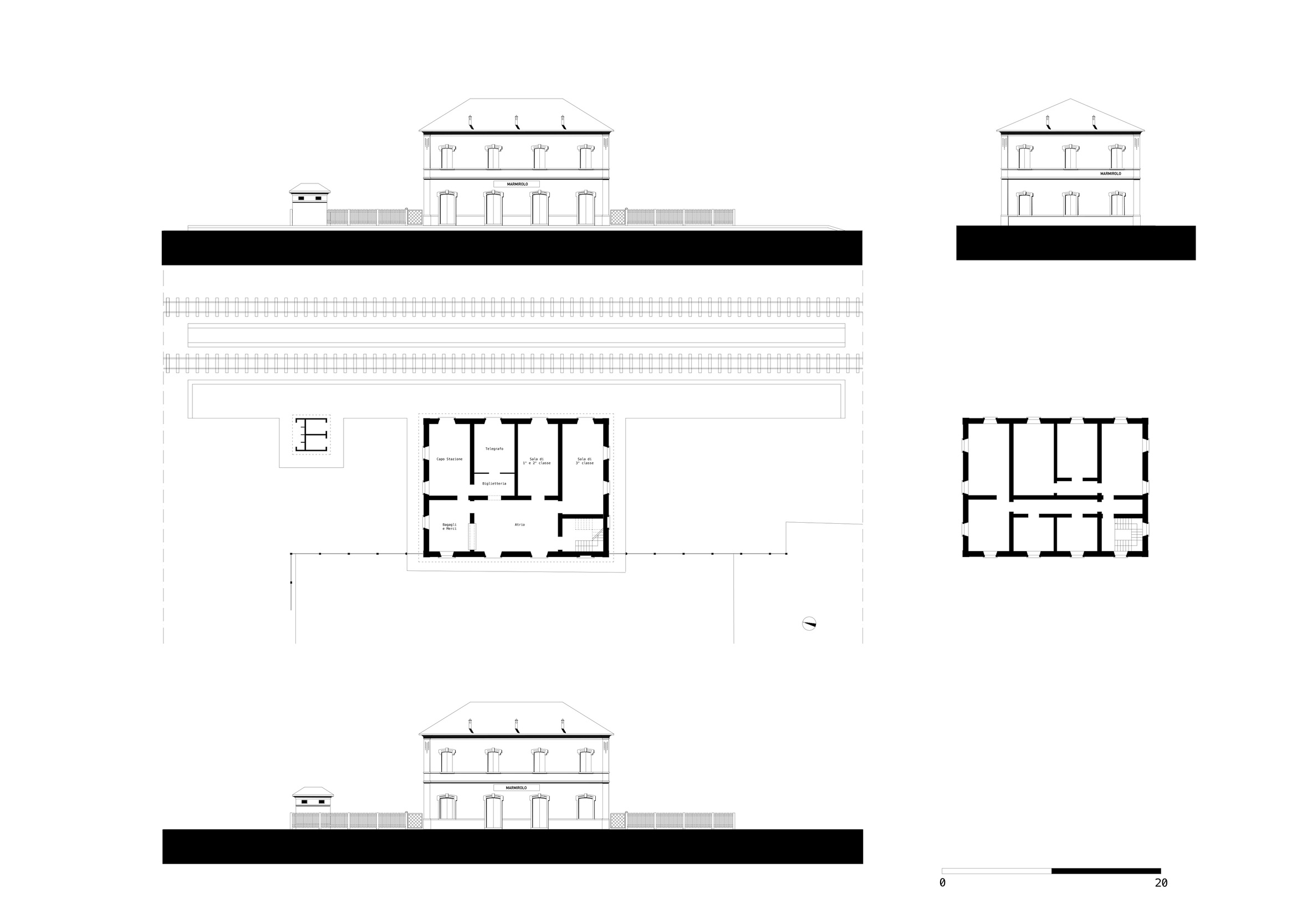

As described in the manuals, the Mantova-Peschiera railway had essential facilities, with five stations and their corresponding goods warehouses in the larger urban centres, one stop with a loading and unloading platform, and two simple stops corresponding to some hamlets, five gatehouses at significant crossings, and a locomotive depot, all distributed at close intervals over a length of 34 km. The signage was absent and replaced by the tireless effort of the railway workers who, in thirty years of work, could guarantee a service, which, already after the Second World War, suffered from a lack of funds for maintenance (Pedrazzini, 2023). This is confirmed by a simple comparison between the first photos of the railway in service preceding the Second World War and those of the 50s and 60s, showing how the Opere d’Arte and their areas of competence were heavily degraded and, in some cases, downgraded in some of their functions as part of the facilities and thus more easily subject to actions of economy and service optimisation.

4. Technical Reports as Gateways

Infrastructure is not only made of technical elements but also places of living. All this is gathered in the text of technical reports attached to preliminary projects, now kept in the archive of the Ministry of Transport, where, in addition to the listing of the technological characteristics of the route and the sizing of the Opere d’Arte there are precise descriptions related to the geography of places and those Paesaggi Umani (Human Landscapes)[3] described in the Touring Club guides or the editions of the magazine Le vie d’Italia from those years (Lonati, 2011). Restitution of an imagined journey that, for those who were passengers, was made up of a double dimension: that within the railway carriage and that related to the framing of the windows open to the landscape and their perception altered by the speed of travel.

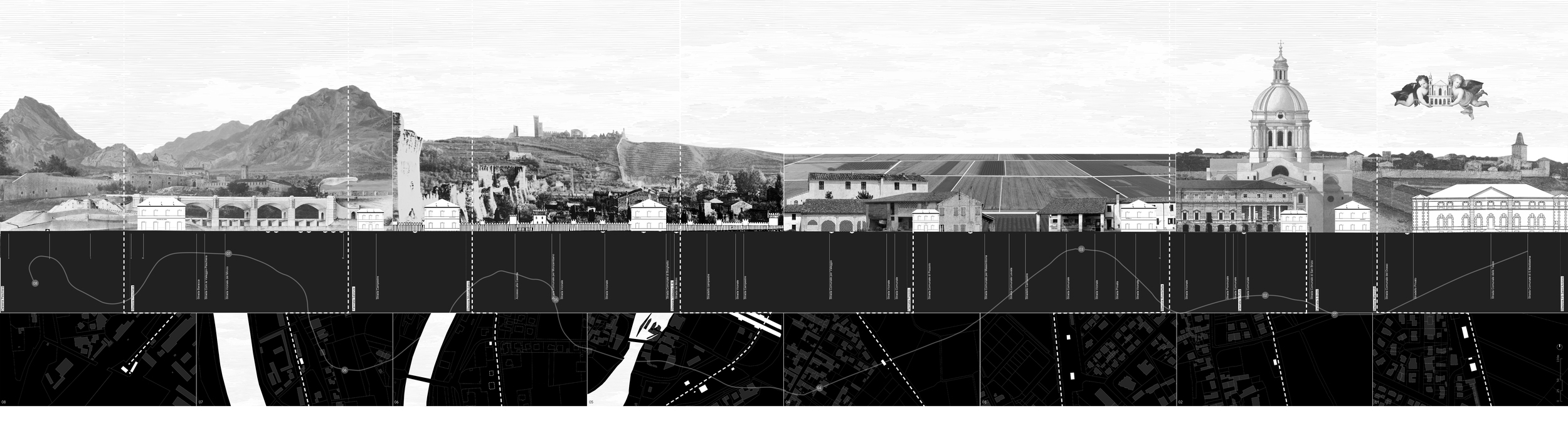

Authors like Schivelbusch (1980) or Marc Desportes (2008) have addressed the perception that these evolutions have had on the spatial framework, starting from the experience of railway travel and a viewpoint that from the train observes all that is interior and the relationship it establishes with the external panoramas: “during train journeys, in fact, a new gaze is forged which we could define as panoramic and whose understanding imposes as a reference the contemporary forms of expression, such as photography or painting” (Desportes, 2008, p. 85).

From the confines of the compartment and the isolation of reading, the landscape that could be seen from the geometric frame of the window is a landscape that can only be observed: “a landscape crossed according to a mechanical shift and not encountered with one’s own movement” (Desportes, 2008, p. 110). The literary landscape of novels, the texts in guides, and the engravings within them offered an invitation to discover the places beyond that quick snippet seen from the window. A series of snapshots of a journey, perhaps like the one collected in the book ‘Viaggio in Italia’ by Luigi Ghirri and Leone (1984).

Using Hugo’s poetic description, the journey can be imagined as “a magnificent motion that must be felt to be appreciated of unheard-of rapidity. The flowers along the railway are no longer flowers but stains or rather stripes of red or white; there are no more points, only lines; the wheat turns into long blonde hair, the alfalfa into long green braids […]; occasionally, a shadow, a shape, a spectre standing, appears and vanishes like a flash beside the door; it is a railway worker who, as is customary, salutes the train” (Gély, 1987, p. 611).

The traveller becomes a spectator who does not partake in the action of the journey. If, on the one hand, the view from the window is characterised by the constant change that seems to shift focus to the distant horizon, on the other hand, the traveller has the opportunity to capture a fleeting detail in sharp clarity.

“To say that nothing can be seen from the window of a compartment has become a commonplace […]. It’s true that an inattentive eye sees only a hedge or a line of telegraph poles. But after training myself for three years, getting into the habit of looking, I have made reports and sketched landscapes […] from the window of a carriage. However, I do not advise describing a foreign country solely from the window of a carriage, because the condition for doing so is simply to know everything beforehand. The autopsy then becomes merely a confirmation of what we already know” (Strindberg, 1889, p. 108).

Following the instructions in the Technical Report for the Project of secondary railways like the Mantova-Peschiera, “it is now possible to rewrite an imaginary of the Mantua-Peschiera journey. A journey characterised not by the mere technical description of the railway but one in which the territory and its various landscapes are introduced: quoting ancient and partly forgotten place names and monumental features of the built environment that have disappeared or transformed profoundly and creating a hypothetical itinerary that, like the imaginary of the railway itself with its layout and its artefacts, is made up of traces, whether they are still recognisable or have completely vanished” (Marcolini, 2021, p. 205).

This is a reading as Marco Belpoliti did for “Pianura” (2021), or the journey by the heteronym of Vittorio Magnago Lampugnani, Vittorio Valori Perduti (Triennale di Milano, 1987), observing places guided by the works of ancient connoisseurs or by historical documents such as maps, plans, paintings, photographs, etc. It is a complex gaze, laden with different experiences and made from an “I observe” suggested by Gregotti (2014), and understood as a subjective view of a geography that, starting from the places listed in the technical report, looks beyond those individual facts to be able to understand the territory beyond the window, and that, where stations or stops are present, offers itself for discovery (Marcolini, 2021).

Engineer Arvedi’s description for the Technical Project Report of the Mantova-Peschiera railway contains a brief but significant description of the Mincio Valley and its river. An image that no longer exists except as profoundly altered, where the river’s blue waters “pass quickly under the arches of the Visconteo Bridge” (Arvedi, 1905), which at that time was still interrupted. The ruin, an ideal subject for a pastoral scene of the late eighteenth century, was home to gardens and meadows where shepherds brought their flocks to graze. Throughout the first half of the twentieth century, it was a favoured subject of some local photographers like Giovetti and Calzolari[4]. Descending the river, the description swiftly mentions the towns brushed by the river and, upon reaching Mantova, describes the city as it was: an island surrounded by waters like the depicted image in the XVIth century fresco by Ignazio Danti in the Vatican Palaces. To support the description, a 1:25000 scale map was created, the outcome of a probable reworking of an old late nineteenth-century IGM - map (Military Geographic Institute), which, cleansed from the analytical excesses of the military technicians, represents what was essential of that territory to highlight the designed line better. A drawn journey, where the two-dimensionality of the map complements the generous technical project report in which some of the built environment was also cited as if to underline their value and importance. The landscapes were multiple and often similar to those described in the surveys of the late nineteenth century, in which, leaving the city of Mantova, “after crossing the lakes on two sides, and the reeds and marshes that still dishonourably surround the city from the others, the lands present themselves with an aspect that is characteristic of all those of the province’s lowlands, both for the conformity of the system and for how they are cultivated with varying diligence” (Magri, 1879). A province always agricultural, as demonstrated by the fairy tales collected by Isaia Visentini at the end of the nineteenth century, which Calvino describes as characterised by a “dominant peasant colouring of the Mantuan narrative folklore” (Calvino, 1970), where well-known heroes of familiar tales are transformed into the inhabitants of those places, where Hercules is a labourer, or the three little pigs become three sisters. Mantuan stories populate the minds of those who live in these places and which the railway has certainly seen built, and that some curious photographer did not fail to immortalise, perhaps struck by that “great” white tongue of broken stones on which until the '50s a passenger convoy pulled by a steam locomotive would pass. Those who would have taken the train for Peschiera would have found the possibility to purchase a first or third-class ticket. Starting from Mantova, the first stretch would have been on the Mantova-Verona tracks, but at Sant’Antonio, it would have left the long Habsburg railway to begin a slow journey, made of many stops where the Mantuan countryside still offered suggestions tied to the nineteenth-century descriptions of some foreign travellers who, having visited the city of Mantova, ventured beyond the lakes, northwards, in search of the ruins of La Favorita or the Bosco Fontana Hunting Lodge (Cf. Schizzerotto, 1981). Along the route, beyond the changing images that could be enjoyed from the window, one would have seen railway workers busy at the stations or in the few signal boxes present. A life not directly known but which we can imagine to be similar to that described by Guido Sostaro in the memories related to the Suzzara-Ferrara railway, where being a railway worker was a privilege compared to those who worked the land (Sostaro, 2009). It is a journey to discover a real country, made of people who have redeemed this territory, and which is sought to be reconstructed starting from the only “exhaustive” document left: the Preliminary Project of Engineer Arvedo Arvedi from 1905 (Arvedi, 1905). Like a literary trace, the document has allowed the identification of a selection of “territorial objects” that are part of the historical fabric of the territory and which Eugenio Turri defines as “indelible data, incorporated into the territorial fabric” (Turri, 2002). The “mental” journey, a condition of a hermeneutic activity, sees the Mantova Peschiera route divided into four parts, where each is introduced by a section of the map corresponding to the concerned stretch, alongside an excerpt from the corresponding Technical Project Report. The documents are then accompanied by a series of zenithal photographs taken in the summer of 2019 with the help of a drone, on which the disappeared route has been redrawn in the form of a dashed line or double continuous line. The images are taken from a height of 70m and provide a snapshot of what remains of the route described by Engineer Arvedi, which has been given a geographical reference in the cartographic productions. Along the routes, it was then chosen to “dwell” on themes taken and deduced from the representation of the early twentieth century as emerging or cited in the project report: the system of suburban villas north of Mantova, the countryside between Marmirolo and Salionze, the Visconteo Bridge of Valeggio, and the complex of Austrian forts around Peschiera. Places described by connoisseurs such as photographers and historians who have produced precious documents made of memories that in the research are evoked in the form of text, capable of returning a subjective reality through architecture and whose documents have been consulted and selected here. Furthermore, a map has been produced to which the Railway Panorama of the Mincio Valley is connected, which, in the form of a collage, creates in elevation the metonymic profile of the identified microgeographies in which the dimension of railway travel returns and which, as defined by Marc Desportes “forges a new gaze that we could define as panoramic and whose understanding imposes as a reference contemporary forms of expression, such as photography, painting, …” (2008, p. 85).

5. Conclusion

This research has unveiled the multifaceted relationship between railways and their surrounding landscapes, emphasising the physical and narrative connections they forge. Through the lens of the Mantova-Peschiera branch line, this study has sought to capture the essence of railway travel and its enduring impact on collective imaginery and identity.

The necessity of a detailed examination of such a minor element of the railway network is underscored by the ambition to envision its regeneration. The underlying thesis of this paper is to explain the architectural significance of these lines further, advocating for their conservation and preserving their Infrastruttura and Soprastruttura with its Opere d’Arte.

The research underscores the economic constraints that have historically shaped their development by recognising the unique character of the Mantova-Peschiera railway and its counterparts. These constraints have necessitated the ingenious use of local resources and afforded specific creativity in designing the elements of the railway infrastructure.

This study has been enriched by the historical and technical insights assembled from archival documents, which simplified the reconstruction of the railway’s history. The contributions of railway manuals, particularly those by Engineer Stanislao Fadda, have been instrumental in this endeavour.

As railways evolve, the passenger’s experience remains unchanged as a spectator of the shifting landscape. This constant is a thread that runs through the narrative of railway travel, from its inception to the age of high-speed trains and beyond, the realm of futuristic concepts like the Hyperloop.

The paper delves into juxtaposing the tangible railway infrastructure with the elusive panoramas glimpsed from train windows, mapping an interlaced journey from Mantova to Peschiera. It is a journey that reconstructs a subjective reality, informed by cultural memory and the relics of the land’s history, where architecture stands as a testament to a shared heritage.

These narratives, inspired by diverse perspectives, contribute to a methodology that narrates places’ physical and lived experiences. In the case of the Mantova-Peschiera, they present the line as a palimpsest, where the territory becomes a text layered with meaning and ripe for interpretation.

In sum, the journey along the Mantova-Peschiera railway is an invitation to rediscover and reimagine the valley’s landscapes. This hermeneutic exploration stitches together historical documents and the enduring marks upon the land. It proposes a re-engagement with these ‘archaeological’ traces, envisioning a future where the historical significance of railways is celebrated and integrated into the contemporary fabric of the territory.

Law No. 5002 (Baccarini) of July 29, 1879, for the construction of new lines to complete the railway network of the Italian Kingdom, proposed the use of economical systems of construction and operation for all those railways that did not have the characteristics of main lines.

The reason for this direct reference to French scientific literature is due to the ability of French engineers not only to create significant railway works but also to write project reports aimed at a series of publications designed to share experiences for a faster technological development of new communication routes

Within “Paesaggi Umani” by Toruing Club, Umberto Bonapace referes to the human landscapes as places “deeply shaped by human work”. Within the volume, a series of images represented the extent of the landscapes and invited to dive into a journey through the Italian territories to admire “the endless range of interventions that humans have made on the environment” (Bonapace, 1977, p. 9). At the same time, the change already underway was denounced, in which “the resurgence of erosive phenomena, the expansion of scrub and forest at the expense of poor crops, the abandonment of the most disadvantaged centers (in the mountains and hills), are plain for all to see” (Bonapace, 1977, p. 10) and that today are the main description of vast areas of Italian territory.

Nowadays, the rich heritage of images these photographers left is stored at the Archivio di Stato archive in Mantua.