A ‘lede’: As part of a recent competition I participated in, I explored the condition of forced eviction from a site, where only minimal traces remain. The condition led me to investigate the spatial and temporal capacity of traces as sites of memory — not only as material witnesses that recollect past events or recall absent subjects but also as storytellers that facilitate repair and reconstruction.

The competition was to design a school for Palestinian children in Khan al-Ahmar, located to the east of Jerusalem — within the ‘Area C Zone’ in the West Bank.[1] The site has a particular condition as Palestinians there are under the constant threat of being forcibly evicted from the site. In response, the competition brief asked the participants to “design a mobile school constructed from lightweight materials [that] can be easily relocated in case of demolition threats, ensuring uninterrupted education for Palestinian children.” (Schools for Palestine, 2024)

The brief evoked a series of questions about what form of architecture an educational environment would take under the constant threat of demolition — leaving a minimal trace or remain behind. And as such, what relationships might emerge from these traces and residues, whether material or immaterial, as sites of memory? My design proposal, in response to the competition brief, utilizes the school as a testbed to explore the site’s ground conditions and force field while giving material form to its broader set of relationships — particularly to what a learning environment becomes under conditions of precarity.

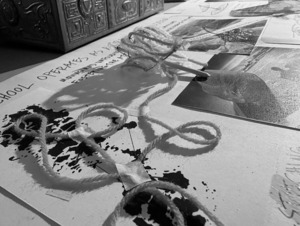

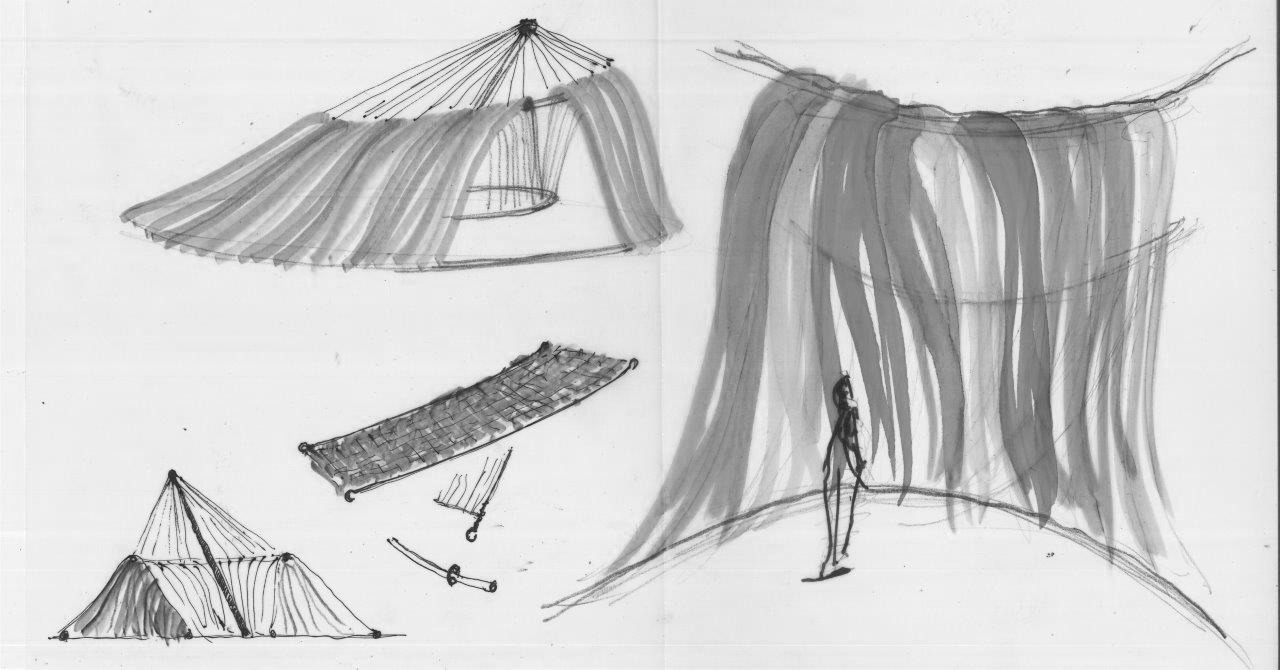

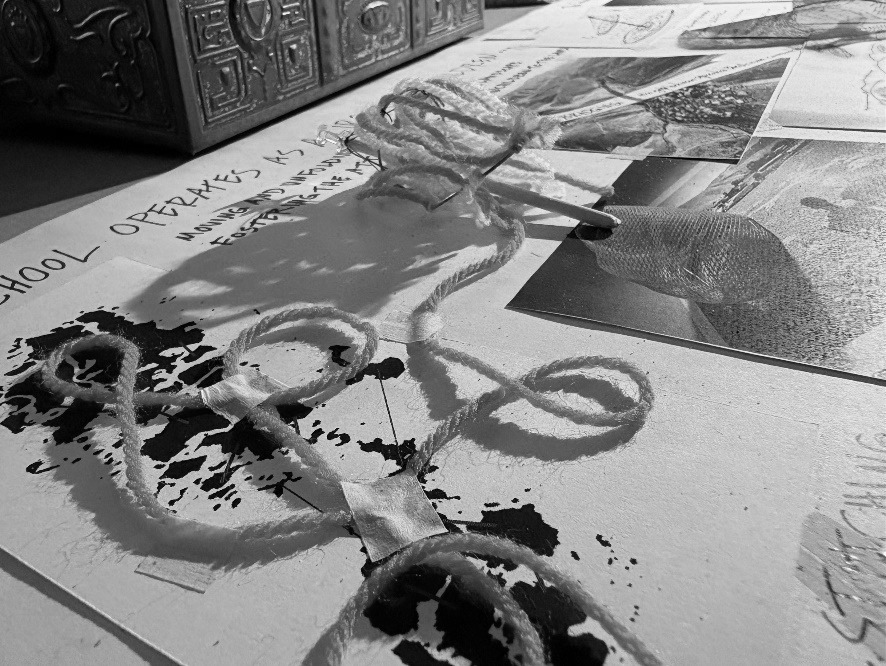

As a thought experiment, the school is envisioned as a circus tent for children. A cloth-like envelope, made of fabric strips woven by the schoolchildren, is proposed as a canvas upon which they can project their memories and hopes. In this sense, the school is not only about its physical entity, but also about being a “situation” to be experimented with — an event, a network of emotions, energies, and social relations. And in the case of the competition’s site and its precarious condition, the ambition is to think of the school as an experiment to test the limits of freedom through the questions of mobility, traces and memory.

In my competition entry, the school is envisioned as a field of bodies, objects, and energies (as sketched in Figure 1), centered around a malleable circus tent — not only to weave children’s hopes for a liberated future, but also to bridge stories and memories across generations, geographies, and cultures. Proposing the school as a circus for children carries another meaning as well: it relates to the movement of evicted children to other places, and equally the transportation of objects and fragments from the site with them. As part of my competition entry board, a key aspect of my proposal, as I stated, is the perception of the school as a ‘collective’: “the school’s body is, in fact, the collective body of children. It moves with them, is mobilized by them, and, in turn, mobilizes their bodies and shapes their dreams.” As depicted in Figures 1 and 2, this reciprocal relationship is materialized through the imagining of the school as “a fragment of Khan al-Ahmar ground, holding and fostering the community’s social relations. The school inhabits the land, gathering people, stories, and memories. Traveling with the children as they carry a fragment of the ground with them.” And, as such, social relations and attachment to the land are maintained and fostered by the very materiality of the fabric tent, despite its fragility and ephemerality.

At the architectural level (Figure 3), the proposed school is built and mobilized through its modularity: the textile pieces are produced by children using their chairs as looms, and when relocation is necessary, the school’s components are packed and carried by the children themselves. In this sense, children carry the school-as-circus wherever they go. The site itself is also carried with them, as sand and earth grains become embedded in the fabric’s threads. The fabric parts — and the boxes in which they are packed — act, in turn, as a material index of the sites they have moved from.

The proposed school, therefore, not only re-stitches the fragmented Palestinian landscape and communities through its movement — openly producing and transmitting knowledge wherever it lands — but also fosters the attachment of Palestinian children to the land from which they have been evicted. That attachment is manifested in a material form, whether that is through the material traces and remains left on the evicted site, or through the sample material remnants and fragments (of the school and the site) carried and transported by children, or ultimately the use of found traces and remnants for reconstruction upon return to the evicted site.

This condition of forced eviction from land, leaving marks and traces on its surface as material witnesses of previous inhabitation is what motivated me to write this essay in relation to memory. To do so, let us begin with the following questions as a point of departure for the essay, aiming to later explore what it means to approach material traces as architecture, particularly when they are linked to a traumatic memory: What role does memory play in this particular condition? And what is the capacity of traces and remnants, as sites of memory, to establish relationships — including those between the interiority of the dispossessed subject and the evicted site, and between the traces and the reader?

There are different meanings of memory in architecture and urban planning. Exploring the available literature materials reveals how scholars use the term to address different topics and experiences. Some associate it with cultural heritage, where memory is seen as a carrier of, mostly positive, accounts of past events linked to architectural and urban fabrics — this perspective frequently leads to the conservation of memorial artifacts, whether in the form of cultural objects displayed in museums, memorial edifices and monuments staged in cities, or preserved archaeological sites. There are those who engage with the memory of the city or a ritual from a phenomenological perspective, examining the relationship between the citizen subject and the city fabric, including forms of attachment to place and its architectural elements over time. But there are also those who link memory to a condition of crisis — such as the memory of a place after its destruction by a natural catastrophe or the devastation of urban areas by war — in an attempt to guide urban reconstruction.

Memory, then, is often associated with architecture from a humanistic perspective, tied to a richly positive framework. In this essay, however, I will focus on memory in a more traumatic condition — where things are registered as a memory or witness to something that has been removed by violence or the threat of violence. Specifically, I will deploy memory as an attempt to explore the condition of Khan al-Ahmar as a site and the limits of memory under its circumstances. I will take the school’s competition as an exercise to explore these aspects of memory, and in particular, the material and temporal limits of memory in the case of a site being evicted by violence or the threat of violence. This, in turn, raises the question about the act of recalling and recollecting memory and its meaning, especially in relation to a traumatizing memory unfolding on a site that has borne witness to.

To approach this condition, then, I wonder whether looking at the minimal traces left behind when the site is forcibly evacuated might offer a glimpse of the people and objects that once inhabited it. I would argue that such traces are charged with the traumatic memory of the eviction event, and as such, they have the capacity to be treated as vessels of memory. But what does it mean to look and read traces as architecture? And in turn, what latent capacity lies within these material traces to carry human memories — vessels of stories and cultures held in suspension? And so, how should we approach a trace from the past, or perhaps the future, whether it be material or temporal?

Before delving deeper into the relationship between material traces and human memories, it is important to unpack and examine the meaning of ‘trace.’ Athar al-farasha (The Trace of the Butterfly), a prose poem by Mahmoud Darwish (2008), a Palestinian poet, may help us do so. He writes:

We may notice that the poem above alludes to the meaning of trace. The word has a rich etymological layers that resonate with themes of memory, absence and ephemerality. The English word trace comes from the Old French tracer, meaning to follow, pursue, or draw, which itself derives from the Latin tractus, the past participle of trahere, meaning to draw, drag, or pull (Trace | Etymology of Trace by Etymonline, n.d.). Traces, according to the Oxford English Dictionary, are ‘vestiges or marks remaining and indicating the former presence, existence, or action of something.’ The word also derives from the verb to trace, meaning ‘to discover evidence of the existence or occurrence of; to find traces of’ (Trace, n.1 Meanings, Etymology and More | Oxford English Dictionary, n.d.).

To trace, then, is to mark or leave behind a line or minimal condition — something both present and pointing toward what has passed. Yet the word also carries connotations of what remains — minute, faint marks, imprints, or lingering signs of something no longer fully there. Weaving in Darwish’s poem as a way to think through traces in the context of the competition’s site and its condition of precarity, the trace evokes a delicate, fragile, almost imperceptible imprint — like that of a butterfly. It is a presence that marks itself precisely through its lightness, hinting at fragility, loss, and the persistence of memory.

Framed in this way, and to further unpack the term, traces are closely linked to the notion of a ‘glimpse.’ In his essay, ‘Glimpses: Between Appearance and Disappearance,’ Georges Didi-Huberman (2016) argues that glimpses are “snippets of things or events that appear before my eyes… but on their way to disappearing.” He then adds that he uses the term glimpses when “the thing that appears leaves, before it disappears, something like the trail of a question, memory or desire”[2] (p. 109). In this sense, trace and glimpse share this quality of being on the point of disappearance — capturing the tension between presence and absence, both holding onto something just before it slips away. And by being on that threshold, they gesture toward what was, leaving a faint but persistent imprint that resists erasure and refuses to be forgotten.

When discussing memory in relation to architecture — particularly architectural restoration and heritage — the word ‘ruins’ often comes to mind. It refers to material remains that serve as reminders of the past, offering glimpses into the lives and lifestyles of those who once inhabited the place. However, ruins carry a different connotation than that of a trace — a ruin can be a trace, but a trace is not necessarily a ruin.

Unlike ruins, traces — based on the aforementioned definition — are not only less dominant in the landscape, smaller in scale, a minor detail or mark, but also on the verge of disappearance; that is, they are fragile and subtle, facing the threat of destruction and erasure. For example, the remains of peasant houses, wells, sanasel (stone terraces), olive trees and cactus are among the traces of over 500 Palestinian villages destroyed in 1948 during al-Nakba (the Palestinian Catastrophe). These traces have been systematically subjected to destruction and erasure pushing them to the brink of disappearance. This process has almost eradicated and obscured the place’s identity and, in turn, its memory.

In this sense, we may also associate traces with a condition of precarity, in contrast to ruins, which are often stable and sometimes staged as monuments or displayed as artifacts in museums. This condition, much like that of the competition site, echoes a broader condition within the Palestinian landscape in the present time. Thus, things, as traces, acquire intensified meaning and memory despite their minute presence because of this. In other words, and in the case of Khan al-Ahmar, the eloquence of fragility born from dispossession — if Palestinian children are forcibly evicted — would amplify the meaning of traces that insist on being remembered. In a way, the fragile traces of life, memory, and culture linger on the edge of disappearance, yet endure. It is precisely because traces are fragile and easily destroyed that possess a particular strength as they are often overlooked or unseen by those who fail to notice or recognize small remains, which, paradoxically, enables their endurance.

That being said, we then may notice a shift from the positivist humanistic approach to memory in relation to material remains; that is, the relationship between the remain and memory has inverted due to the political circumstances. Whereas the remain was once associated with ‘ruins’ — visible, monumental, and settled — it is in the Palestinian condition that is marginal, fragile, and on the verge of disappearance; a trace. This is not to undermine the role of ruins as strong evidence for people’s claims of place — claims of land ownership and possession are often built upon ruins.

Now, recognizing the fragility of traces raises the question of how they should be approached. Returning to Darwish’s poem reveals another aspect of traces: they are imperceptible or, to use Darwish’s words, they “cannot be seen” when speaking of the trace of a butterfly. Imperceptible — or not perceived by the senses — not only due to their minute scale, but because they require a particular way of looking and reading: paying close attention to marginal things and minor details, coupled with sensibility and carefulness, so that the eyes and senses can detect and engage with them.

This materially sensitive approach — an active reading of small things at the edge to recall memories and stories — may remind us of one meaning of tracing: “to track down, follow the trail, scent, or footsteps of” (Trace | Etymology of Trace by Etymonline, n.d.). To follow or pursue an absent thing through a trace that indicates its presence, this act of tracking down a mark or sign left by the passage of something, again, requires a particular skill and knowledge, accompanied by a sensitive and careful attention to minor details.

In doing so, we might take on the role of a detective, following the minimal material evidence left at the site — what is often referred to as ‘forensics.’ In his essay ‘Clues: Roots of an Evidential Paradigm,’ Carlo Ginzburg (2013) investigates this approach by drawing a parallel between the methods of Sherlock Holmes (discovering clues by means of footprints, cigarette ashes, and the like), Sigmund Freud (attentively observing symptoms in great detail to diagnose diseases, or reveal hidden individual characteristics) and the artist Giovanni Morelli, whom he credits with the invention of what he calls the “Morellian Method” — a methodology originally used to distinguish original paintings from copies.

“In each case,” Ginsburg (2013) argues, “infinitesimal traces permit the comprehension of a deeper, otherwise unattainable reality: traces - more precisely, symptoms (in the case of Freud), clues (in the case of Sherlock Holmes), pictorial marks (in the case of Morelli)” (p. 101). Ginsburg even goes further to trace the root of this method, assign it to humans as hunters for thousands of years, accumulating knowledge and learning how to “reconstruct the shapes and movements of his invisible prey from tracks on the ground, broken branches, excrement, tufts of hair, entangled feathers, stagnating odors. He learned to sniff out, record, interpret, and classify such infinitesimal traces as trails of spittle.” This rich vessel of knowledge, Ginzburg states, “has been passed down by hunters over the generations” to shape modern forms of interpretation and reading that pay attention to small details and clues (p. 102).

But what does deploying the “Morellian Method” to approach the minimal traces left on a vacated site, particularly in the context of the competition’s site and its condition of precarity, entail? Although the evicted site may appear empty at first glance, insights and visions begin to emerge when attention is paid to the smallest details on-site. And so, when encountering the traces, they give a sense of proximity to those children who left them despite the distance. Walter Benjamin (1982), in ‘The Arcades Project,’ distinguishes between trace and ‘aura’ by stating:

Trace and aura. The trace is appearance of a nearness, however far removed the thing that left it behind may be. The aura is appearance of a distance, however close the thing that calls it forth. In the trace, we gain possession of the thing; in the aura, it takes possession of us. (p. 447)

To trace, therefore, is also to recollect: to call forth a past event or a distant thing. And with the ‘nearness’ that traces bring upon encounter, there is also a proximity to the evicted subject — and, in turn, the traumatic experience of dispossession and forced removal from site. The immediate contact with the traces evokes the shock of immediacy as an affect on our subjectivities as viewers or readers, perhaps even conjuring the haunting presence of children’s shadow apparitions — and the uncanny affect that accompanies it.

Equally, when subjects are evicted from a site, they often carry material objects with them — either a fragment from the site itself, like soil, or personal belongings — to a new place. Based on Benjamin’s perspective, these carried objects have an auratic relationship with the original site, as if the aura and sacredness of the site are carried with the evicted subjects. In a sense, while traces left behind on-site create a sense of closeness regardless of the distance of the subject who left them, auratic objects appear distant regardless of their proximity. Despite the distance, these memory objects act as witnesses to what is lost, carried to a new place and continuing to endure through their own material endurance. Therefore, proposing the school as a mobile circus tent in my competition entry carries a double meaning: while the evicted schoolchildren leave traces on the site, they also carry and transport fragments and objects from the site itself with them, as if carrying the ground with them and maintaining a connection to the original site.

To think through the tent structure in general — and a circus tent in particular — as fragile and ephemeral is to consider its aesthetics in relation to its context and political circumstances. Although the tent’s transient presence suggests mobility, it also reveals the absurdity of the situation; that is, my proposal of a mobile school-as-circus acts as a satirical gesture precisely by adhering to the laws and rules of the environment. In doing so, it has the potential to draw attention and direct the eye toward the Palestinian communities in the area, who face continuous threats of expulsion.

As such, establishing this ‘aesthetic fragility’ in response to the site’s conditions and ethical imperatives — through the medium of a competition in this case — renders the proposed fragile tent a ‘political act’ in itself, as argued by Giovanni Garzón and Sandra Panzza (2023). Alternatively, the tent can be interpreted as a ‘temporal-based phenomenon’ situated in the world as a ‘contingency’ — not a singular, stable, isolated, or autonomous object, but rather one defined “through its engagement with everyday dynamics and the real world,” as Stefano Romano and Valerio Perna argue (2022).

Speaking of shadows and the ghostly presence of children — if the forcible eviction indeed took place, marking a moment of crisis unfolding, experienced, and materialized — what does it mean to encounter the invisible in this case? What forms of relationship does the dispossessed subject maintain with the vacated site and the minimal traces left behind?

When a subject is forcibly removed from a place through violence, where almost everything must go, a minute remnant or residue might be left behind — often in the form of land marks and traces inscribed on the ground’s surface. Therefore, the memories embedded in a vacated site under such traumatic conditions can be retrieved to tell the story of previous inhabitation. In the case of the competition site, the schoolchildren would likely have left traces of their play — so minimal and subtle that they are almost ‘imperceptible.’ A relationship is then established between the absent actant — a child who is no longer physically present on-site — and the material trace they leave behind. As such, the evicted child is neither fully present nor entirely gone; instead, their minute presence — through the fragile traces left on-site — can be re-called and remembered through active reading, which in turn fosters their relationship with the place.

In this way, traces are indexical: they have a strong connection to the evicted children despite the distance. The ‘doubleness’ of these material traces not only helps to reconstruct a memory or narrative of the children’s past presence but, at the same time, takes us on a journey to an imaginary site that resides between the evicted site and wherever the evicted children are located. Traces, in this sense, orient our attention to the condition of precarity under which those children are living, but more importantly, they leave an affect on the reader’s subjectivity while trying to decipher them, potentially evoking an action driven by a moral imperative. In relation to this, Jasper Johns (as cited in Ginzburg, 2013) states: “An object which speaks of the loss, of the destruction, of the disappearance of objects. It does not speak of itself. It speaks of others. Will it also include them?” (p. 96)

The dispossessed children, in this sense, claim ownership of the land, despite the distance, through the material traces entangled with them, acknowledging the memory of place and the history of dispossession that it bore witness to. Children may no longer be physically present on-site, but the story of their absence is mediated through traces of past encounters — likely violent ones. Their ghostly presence may hint at the injustice that took place, with the traces serving as material evidence — witnesses to a historical rupture. A call for justice lingers through the traces and the shadows of children attached to them, demanding redress until their rights are restored.

Though marked by its own particular condition, the competition site is also connected to other sites of oppression and violence across the globe, especially when considering the haunting scar of violence and the traumatic affects it leaves behind when the site is forcibly evicted (Figure 5). Examples of other contexts of forced eviction or spatial dispossession include the Rohingya camps and the expulsion of over 700,000 Rohingya Muslims to Bangladesh, where homes were destroyed and land seized — severely affecting communities and their ties to the land from which they were displaced. Similar patterns are seen in the demolished townships under South Africa’s apartheid regime, including the forced removals that began in 1966 in District Six, which was declared a “whites-only” area under the Group Areas Act. Over 60,000 residents, mostly Black and Coloured South Africans, were forcibly removed and their homes bulldozed.

So far, we have explored the capacity of traces, charged with memories and experiences, to hint at something beyond their materiality. Paying close attention to traces, therefore, is to re-call a past event, a distant site, or even an absent subject. In doing so, I cannot help but wonder: Who recalls a memory? Who is the intended audience? And to what purpose?

A reader of traces may “decipher” their meanings and relationships with other agents and things upon encounter. Equally, this process facilitates the re-construction of a narrative, or a sequence of events that took place, excavating the memory that the traces signify. This quality of traces may remind us of storytelling and its power to construct a narrative — utilizing the inherited skills and knowledge to do so, as Ginzburg (2013) argues, from the old hunter who “would have been the first “to tell a story” because he alone was able to read, in the silent, nearly imperceptible tracks left by his prey, a coherent sequence of events.” (p. 103)

And so, if we attentively look at the fragile traces and marks inscribed on a vacated site and its ground’s surfaces, we can sense them vibrating with the lingering charge of memories that may have been long forgotten. If we listen closely to the ghostly whispers and shadowy apparitions that inhabit the site, we might hear resonant sounds and voices striving to share their untold stories. If we gently touch a delicate remnant left on site, we might uncover and unfold its material layers, drawing distant fragments together into a whole.

A return to a lost memory is, therefore, a return to a lost childhood, hidden in the shadows. It is a child at play, where traces of the past and future converge with the present, and the imaginary merges with reality, awaiting rediscovery.

Acknowledgement

I am grateful to my supervisors Professor Mark Dorrian and Dr. Ana Bonet Miró for the fruitful discussions during my PhD journey at the University of Edinburgh. This essay would not have been possible without their invaluable input.

In particular, Khan al-Ahmar is located at a strategic site along the “E1 corridor,” which not only divides the landscape and separates Palestinian communities from one another, but also splits the West Bank into northern and southern sections. Hence, Israeli control over this corridor disrupts the geographic contiguity of the West Bank while obstructing Palestinian movement. As Adam Tanaka (2014) argues in his exploration of the relationship between the car and the spatialization of social inequality in São Paulo, Brazil, “transport modes play a central role in mediating and reproducing broader societal power relations” —complicating the often-perceived notion of the car and its associated infrastructures as “apolitical technologies,” especially in the context of urban segregation. (p.19)

I owe the idea of looking at something on the verge of disappearance in terms of glimpses to Dr. Ella Chmielewska (conversation, 2022).