1. Definition of the problem, research questions, and methodology

Aleppo, one of the oldest continuously inhabited cities in the Levant and Syria’s second-largest metropolis, has long stood as a cultural and architectural landmark. Since 2012, however, it has faced catastrophic destruction due to the Syrian Civil War. The eastern districts, home to many informal settlements, have suffered disproportionately. These neighborhoods are more than just physical spaces, they are repositories of collective memory, social cohesion, and lived identity.

Unlike the western, state-planned districts of Aleppo, these informal areas grew organically through community initiative, shaped by rural traditions and bottom-up spatial practices (Al Hamoud, 2022). Narrow alleys, dense courtyards, and intimate public spaces characterize their form and reflect the everyday lives of their residents. Built through need rather than imposed planning, these settlements embody a distinct architectural and cultural identity.

This article argues for the preservation not only of the physical fabric of Aleppo’s informal settlements, but also of their intangible cultural heritage. In particular, their social structures and collective memory. A research question guides this inquiry: how can post-conflict reconstruction honor the identity defining features and cherished memories of these neighborhoods, while addressing their vulnerabilities?

Reconstruction projects too often treat war-torn areas as “blank slates,” a pattern observed in numerous contexts worldwide (Al Hamoud, 2022). As demonstrated in Beirut and Sarajevo, the imposition of imported urban models has frequently disrupted cultural continuity and alienated local communities (Vale, 2005). In Lübeck, rigid geometric zoning schemes failed when applied to organically developed districts (Caja, 2021). Similarly, Chukwuemeka (2022), in his study of Onitsha markets in Nigeria, warns of the social fragmentation caused by spatial designs disconnected from local practices, which led to weakened community ties and reduced cooperation among traders. Therefore, this research, advocates for a participatory and culturally grounded approach to rebuilding Aleppo’s informal settlements. Rather than relying on standardized models, the article emphasizes the value of incremental reconstruction guided by the principle of “building the new from the old.” This reflects what Borràs (2024) observes in the Portuguese context, where the reuse of existing structures bridges historical continuity and new design. By recognizing residents as co-creators of their spaces, and drawing upon vernacular knowledge, we can develop more meaningful and context-sensitive urban futures.

The first section of the article examines the history and development of Aleppo’s informal settlements before the conflict, illustrating how collective memory shaped the identity of these communities. The second section focuses on architectural design for socially inclusive reconstruction. By using architectural design as a research method, experimental designs are proposed and assessed to ensure that the rebuilt settlements retain their original essence.

In conclusion, this study underscores the potential of informal settlements especially their collective memory, to inspire innovative, sustainable, and locally grounded housing models. This research contributes to the literature on Aleppo’s reconstruction, offering adaptable approaches for crisis-affected regions and highlighting the importance of memory in sustaining community identity and guiding future development.

2. Analysis

With a population of around 2.3 million, Aleppo has long played a central role in Syria’s social and economic landscape. Today, the city bears deep scars from the conflict that began in 2012 especially in its eastern districts, where informal settlements were concentrated and heavily targeted because they were strongholds of the revolution against the former regime. According to the Norwegian Refugee Council (2025), nearly 80% of homes in these areas are uninhabitable.

The destruction of these neighborhoods is not simply material; it represents an assault on cultural memory and collective identity. Informal settlements were often targeted intentionally, perceived as revolutionary strongholds. Their erasure was both physical and symbolic, disrupting residents’ sense of belonging and weakening their social fabric. Halbwachs (1992) concept of memory as “a reconstruction of the past using data from the present” frames memory as a dynamic process shaped by individual and collective experiences. Bevan (2004) further argues that violence against buildings constitutes violence against memory and identity, highlighting the importance of safeguarding cultural heritage during reconstruction. Mubarak (2007) emphasizes that home forms the foundation of identity, while Pallasmaa (2023) discusses the psychological trauma of “existential homelessness,” illustrating the deep impact of losing one’s place of memory. Finally, Till (2009) suggests that architecture is always provisional dependent on people, place, and memory which is especially critical in post-conflict contexts.Together, these perspectives emphasize the vital importance of preserving memory and identity in efforts to rebuild and heal communities affected by conflict.

Informal settlements in Aleppo emerged over the past few decades due to the state’s inability to meet housing demand, driven by economic hardship and rapid urban migration. According to Wakely et al. (2009), 22 such areas are officially classified as illegal, covering nearly one-third of the city’s built-up area. These neighborhoods fall into two categories: some, like Sheikh Fares and Jabal Badro, were developed on private farmland and follow a grid-like pattern; others, such as Al-Nairab Camp, emerged on unutilized state-owned land.

As Al Hamoud (2022) explains, property ownership in these areas is insecure and typically unregistered, with land transactions often based on informal agreements. Many plots, originally agricultural, were sold and developed without formal approval, and in most cases, the same individual owns both the land and the house, with minimal tenancy or rental arrangements.

The residents of these informal areas primarily come from low-income backgrounds. Many migrated from rural regions in search of work; others remained because of the strong social bonds found in these close-knit communities (Al Hamoud, 2022). Social life is shaped by traditional structures. Extended families—often spanning three or more generations—commonly live together. Sons typically stay in the family home after marriage, while daughters typically move in with their husbands, joining their husbands’ extended families.

Gender roles are deeply traditional, as Al Hamoud (2022) notes, with men considered household guardians while women, particularly in informal areas, are often excluded from public life and focus on domestic responsibilities. Educational access is limited, especially for girls, with most children attending only the mandatory schooling years, up to age 12. Employment is concentrated in Aleppo’s industrial sector, where many men work as carpenters, tailors, or painters; however, Schellenberg and Gleischmann (2000) note that a significant portion of the population remains unemployed. These socio-economic conditions collectively shape the lived experiences and opportunities of residents in Aleppo’s informal settlements.

Schellenberg and Gleischmann (2000) describe informal settlements as developing in an organic, incremental manner, with most buildings standing two to four stories tall and constructed progressively according to necessity and available resources. Initial dwellings often used mud or brick, while later structures incorporated concrete blocks and cement. However, further expansion was frequently hindered by economic constraints. This pattern of gradual architectural change reveals both the resilience and the limitations experienced by residents.

According to Wakely et al. (2009), the predominant housing model in these areas is the inward-facing courtyard house, ranging from 65 to 200 m², designed to ensure privacy with minimal openings to the street and separate entrances. As Bianca (2001) describes. Roof terraces serve multiple purposes such as laundry, sleeping during summer, and household tasks like drying produce or textile production; for women, terraces provide rare access to open space, fostering a sense of autonomy and belonging. Such design elements highlight the intersection of cultural values and practical needs within these communities.

Al Hamoud (2022) highlights that public life extends into the streets, which serve as vital communal spaces for children’s play, weddings, and mourning ceremonies. The pedestrian-oriented layout strengthens social interaction, characterized by limited vehicular infrastructure and few planned public spaces. The prominence of communal street life underscores the importance of social cohesion in these densely populated neighborhoods.

A detailed study of these settlements reveals how spatial and social structures are deeply intertwined. Informal neighborhoods reflect what Turner (1976) calls “housing by people” environments shaped through user needs and participation rather than formal planning. Similar to Alqueries vernacular settlements that adapt to environmental and social contexts (Cabrera Fausto et al., 2020) these neighborhoods developed through internal, community-driven logic.

These structures within informal settlements represent a form of “architecture without architects,” where residents design and build according to necessity, tradition, and a sense of identity. The resulting environments simple, adaptive, and deeply embedded in everyday life are increasingly rare in contemporary urban development. Neighborhoods, streets, and homes are not merely functional spaces; they serve as repositories of collective memory. As Ricoeur (2004) observes, memory is a negotiation between history and identity, constantly reshaped through lived experience. In this context, the destruction of such environments represents more than the loss of physical structures it signifies a rupture in collective identity. Architecture, as Assmann (2011) argues, materializes cultural memory. It embeds rituals, values, and continuity into the built environment. Aleppo’s informal settlements with their courtyard houses and layered histories embody this idea, offering a unique and fragile archive of lived culture.

Despite their cultural and social richness, these neighborhoods face serious challenges. High residential density, poor infrastructure, insecure property rights, unstable construction methods, and limited public or green space create complex vulnerabilities. These issues must be addressed, particularly in any future reconstruction efforts.

However, such interventions should not come at the cost of cultural erasure. The value of these settlements lies not just in their physical fabric but in the memory, identity, and resilience they contain. Future planning must strike a balance addressing technical needs while preserving the soul of these communities.

3. Reconstruction Approaches

To address the research question, a specific area (Jabal Badro) within an informal settlement has been selected to explore potential reconstruction strategies. As the analysis demonstrates, informal settlements tend to share common characteristics, making the proposed approach adaptable to various contexts.

Jabal Badro is situated in eastern Aleppo, close to both the city center and an industrial zone. Originally an agricultural area, it was informally settled from around 1980. Prior to the war, the population was approximately 38,000 residents (Wakely et al., 2009), but conflict and displacement have significantly reduced this number.

For the reconstruction of this war-affected settlement, two potential approaches are considered:

4. First Approach

Over the years, Aleppo has relied on standardized housing models for informal settlements. In the past, the city’s municipality implemented these models as a cost-effective and efficient solution, and future reconstruction efforts will likely follow the same pattern. If the standardized approach is adopted, the study area can feature Variant 1: four- to five-story single-family homes, Variant 2: grouped residential units, and Variant 3: linear row complexes (Al Hamoud, 2022).

While these standardized models improve infrastructure and living conditions, they often treat the district as a blank slate, prioritizing mass production over cultural preservation. Typically designed as small apartment blocks with simple layouts, including a living room, kitchen, bathroom, and children’s bedrooms, these structures disrupt the original urban fabric. The introduction of new streets and buildings alters the familiar environment, severing ties with the past.

Unlike Aleppo’s informal settlement neighborhoods, where homes expand vertically to accommodate growing families, these rigid designs lack adaptability. Additionally, international urban planning regulations impose constraints on building heights, spacing, and green areas, leading to low-density, single-use residential districts. Although parks and playgrounds may be incorporated, the result is a uniform, bland aesthetic that fails to reflect the character of the original settlement.

This form of reconstruction does more than reshape the neighborhood, it risks erasing its collective memory. War may have destroyed buildings, but these rigid models threaten a greater loss: replacing familiar streets, homes, and social ties with an environment disconnected from its history.

While offering a structured rebuilding strategy, this method comes with significant risks. War destroys structures, but it does not erase memories. Reconstruction that disregards collective identity can permanently sever residents’ emotional connection to their neighborhood. As Hoteit (2015) warns, reconstruction can sometimes be more destructive than war itself, completing its mission by eliminating the unique essence of a place. This concern echoes the arguments of Vale (2005), who emphasizes that post-disaster rebuilding must address symbolic and cultural loss to enable true recovery.

5. Second Approach

Building upon the research framework established earlier, this section translates those theoretical values memory, identity, and participation into architectural design. The goal is to propose a location-specific reconstruction strategy grounded in spatial justice and cultural continuity. Rather than relying on top-down models, this approach supports resident involvement in the rebuilding process through participatory methods. It reflects what Hamdi (2010) describes as placemaking a process in which users actively contribute to shaping their living environment.

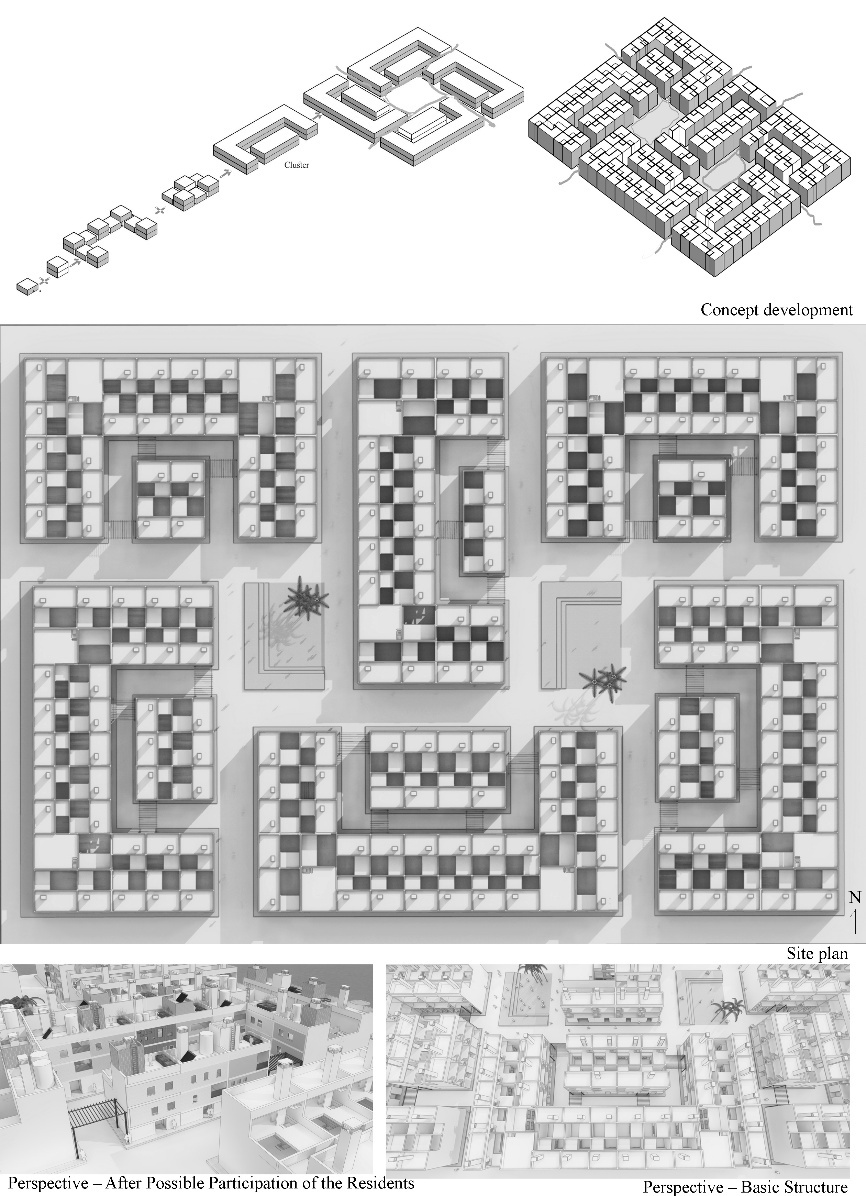

This approach introduces a courtyard house typology combined with the cluster principle as an alternative to conventional models. By applying a specific urban pattern, it creates a dense, well-structured environment. Inspired by the communal and compact living of the traditional courtyard house, this model modernizes and innovatively transforms that design.

Evaluating whether courtyard houses and clustered developments meet contemporary needs while preserving the identity of informal settlements is crucial. This ensures that collective memory and the neighborhood’s original character are reflected in a newly developed form.

As a typology, the Courtyard House model promotes high urban density by enabling expansion on three sides, optimizing land use and reducing façade and insulation costs (Pfeifer & Brauneck, 2008). The flexibility to adjust unit sizes with minimal construction enhances adaptability, while the enclosed nature fosters personalized interior design and minimizes neighbor conflicts. Its inward-facing character creates a tranquil living environment, counterbalancing urban noise (Jan Cremers et al., 2021). This balance between privacy and urban proximity underscores the courtyard house’s enduring relevance in dense city contexts.

The cluster principle, designed for diverse social groups, clusters support community-oriented living through a flexible structure that allows infill development and outward expansion. This adaptability fosters intergenerational living and social cohesion. As Magliacan (2021) notes, negotiating between urban densities and diffuse urbanities is critical to ensure that compact reconstruction models remain socially and spatially livable.

Bürklin and Peterek (2017) describe typological groupings in which clusters integrate various building types freestanding structures, row houses, terraces, courtyards, and block fragments into dynamic spatial compositions. Key spatial concepts, such as connectivity and openness, shape these configurations, often centered around shared spaces like squares or green areas, reinforcing identity and collective memory.

According to Bürklin and Peterek (2017), clusters achieve high urban density while maintaining the character of the existing urban fabric. They also encourage collective building projects, fostering social interaction, shared ownership, and economic benefits through cost-efficient construction.

Cluster housing allows for flexible expansion and self-adaptation, aligning with Dovey’s (2010) argument that such urban forms are not merely functional but are embedded with social and symbolic meaning.

Beyond its theoretical foundation in enhancing social cohesion and preserving identity and collective memory, the cluster principle has proven effective in diverse post-conflict and post-disaster contexts. Notable examples include the reconstruction of Nahr el-Bared Camp in Lebanon (UNRWA, 2010), post-earthquake recovery in Kutch, India (Hunnarshala Foundation, 2008), Chile’s Half a House post-quake project (O’Brien et al., 2020), and incremental housing in Belapur, India (Steinø et al., 2020). These case studies collectively demonstrate how participatory, incremental, and context-sensitive approaches empower communities to plan their environments, resulting in stronger, more cohesive, and locally responsive outcomes. Whether rebuilding in politically constrained refugee settings or upgrading informal settlements, such methods foster dignity, resilience, and cultural continuity. Together, they offer adaptable lessons for sustainable reconstruction in complex environments like post-conflict Aleppo.

By incorporating these principles, this model transforms existing structures into dynamic, adaptable urban environments. More than just housing, it reconnects residents with their collective memory and identity, preserving the neighborhood’s essence while embracing modern needs. Integrating these principles into my own work strengthens my commitment to co-creation, socio-political awareness, and culturally grounded design in post-crisis environments.

6. Urban Design

Unlike the rigid, self-contained housing patterns typical of West Aleppo, this design introduces a more flexible, cluster-based urban structure. The area is reorganized using a “carpet pattern” that weaves together new streets, public spaces, and residential clusters. Land is subdivided into parcels of varying sizes, following a clear classification system to support equitable post-war distribution and lay the groundwork for a future ownership model. The city administration divides the rebuilt area into two sections: one part provides replacement housing for former residents, while the other is sold or rented out.

Drawing inspiration from citizen-led efforts like the Nahr al-Bared reconstruction project (UNRWA, 2010), the plan emphasizes community involvement to ensure fair allocation of property and the restoration of ownership to indigenous residents. Papa and Petërçi (2021) similarly demonstrate how participatory design processes, even through the reuse of recovered materials, can empower communities to actively shape reconstruction. This flexible framework accommodates diverse building typologies, enhancing housing capacity and enabling more efficient land use. The organization operates across three spatial levels:

At the smallest scale, individual plots are grouped into twelve open-layout units, often arranged around a shared central space. These twelve groups are then combined into six larger clusters. While the development is dense and compact, it is counterbalanced by generous and diverse open spaces, all interconnected through a network of neighborhood pathways.

A variety of open spaces and communal squares give each section its own identity. Together with the dense built environment, they create dynamic spatial sequences that blend narrow and wide spaces, shaping a modern and vibrant character.

In traditional housing models of West Aleppo, stairwells function solely as access points. This design approach, however, significantly expands their role. Instead of leading through dark corridors or undefined entrance zones, access to each residential unit is integrated with communal outdoor spaces and garden areas. (Cremer et al., 2019) This eliminates unused buffer green spaces and transforms shared outdoor areas into high-quality living environments.

To ensure comfort even in high temperatures, communal spaces are irregularly shaded with pergola structures. These shaded areas create a pleasant atmosphere and encourage social interaction. Public spaces, in particular, serve as inviting gathering points, playing a crucial role in rebuilding social cohesion after the war. They help restore trust among residents, facilitate conflict resolution, and preserve the community’s collective memory.

This design approach addresses the shortcomings of previous models by improving accessibility, allowing emergency vehicle entry an essential feature often absent in earlier informal layouts. At the same time, it preserves traffic-calmed environments that prioritize pedestrians and cyclists. Parking is placed at the periphery or in designated structures, reducing the visual and spatial dominance of vehicles within residential areas.

7. House design

The plot, as the smallest unit, is fully built over with a house and courtyard, forming an integrated spatial structure. To ensure the functionality of this concept, several design parameters must be considered. The building height is determined by the width of the street, while the entrance area is shielded by a semi-private forecourt to prevent direct views from the street. The courtyard plays a central role not only as a source of light, warmth, and ventilation but also as a social hub that preserves the collective memory of traditional dwelling forms.

According to Hantouch (2009) and Sibley et al. (2004), the optimal orientation of a courtyard follows an east-west axis, with its longer sides extending north or south. This configuration maximizes solar exposure in winter while minimizing heat gain in summer. The courtyard should occupy at least one-sixth of the total built area, with a maximum courtyard-to-living space ratio of 2.5:3. Additionally, the northern façade must be carefully designed to prevent obstructing sunlight for neighboring buildings while also shielding the street from excessive solar exposure.

Beyond its spatial and climatic functions, the courtyard actively contributes to microclimate regulation by enabling natural air circulation through convection. The upper floors should incorporate moderate window openings to facilitate cross-ventilation. These openings allow air currents to flow through the building, enhancing ventilation within the courtyard without compromising the enclosed façade concept. The rooftop terrace, much like the courtyard, serves as both a thermally beneficial space and a social-functional area. It can be used for household activities such as drying food or storing water and oil tanks, while also holding deep cultural significance as a private space for women. As a result, five variants with different residential sizes have been developed based on insights gleaned from the design parameters.

Variant 01 (Angle house) was dismissed due to its unfavorable courtyard orientation. Variant 02 (optimized Angle house) proved to be the most effective solution, offering an optimal courtyard orientation, generous living spaces, high privacy, and reduced noise transmission while maintaining standardized yet flexible layouts. Variant 03 (garden house) allows for maximum courtyard usage and good natural lighting but suffers from high noise transmission and potential disturbances from adjacent buildings. Variant 04 (courtyard access) integrates direct entry into the living space through the courtyard but is impractical in winter and significantly reduces available living space. Variant 05 (U-shaped house) provides effective courtyard orientation and strong noise protection but limits flexibility in stair and bathroom placement.

After weighing all advantages and disadvantages, Variant 02 is recommended, as it offers the best combination of functional courtyard orientation, privacy, living quality, and spatial adaptability. More than just an optimized architectural solution, this concept reinforces identity in residential design while safeguarding the collective memory of communal urban living.

The proposed housing model departs from conventional cluster housing concepts commonly found in European contexts. In Europe, a cluster apartment typically integrates multiple private living units, each containing at least a small bathroom and, in some cases, a private kitchenette. These units are then complemented by shared living, dining, and kitchen areas, fostering communal interaction among individuals from different age groups and family backgrounds. (Prytula et al., 2020).

In the study area, this concept is reinterpreted and adapted to align with local socio-cultural dynamics, ensuring that the design not only responds to spatial efficiency but also preserves the identity of its residents and strengthens their collective memory. The following design strategies are implemented to achieve this balance:

Given the conservative social fabric of the site, where privacy is a primary concern, the cluster is composed of several independent, inward-oriented residential units that are spatially defined and shielded from their surroundings. This approach ensures a sense of enclosure and exclusivity while maintaining the fundamental benefits of clustered living.

These private living units are interconnected through a semi-public communal space, offering a transitional zone between private and shared domains. Residents have the autonomy to determine the degree of engagement with the shared space whether as a social node for interaction and gathering or as a secondary space that remains selectively activated.

The proposed model acknowledges that cluster living encompasses more than just single-family households. It is structured around multi-family housing typologies designed to accommodate a variety of household compositions.

As the spatial requirements of families within multi-family dwellings may vary, the design framework incorporates a flexible and adaptive structure. Various housing sizes and typologies can be combined, allowing for multi-generational living or cohabitation of unrelated families while preserving spatial integrity and autonomy.

To illustrate the adaptability and scalability of this approach, the following section presents various typological configurations. These iterations explore how distinct residential units can be strategically stacked and interwoven within a compact yet dynamic architectural form, ensuring both functional efficiency and the preservation of cultural identity (Koolhaas, 1995; Till & Schneider, 2008).

Variant 1: Designed for large multi-generational families, this typology allows different family units (e.g., parents, children, grandchildren) to reside across multiple floors. One unit can occupy the ground floor, while another remains independent on the upper level. Alternatively, the ground floor can function as a communal living, dining, and kitchen space for the entire family, with the upper level dedicated to private sleeping areas.

Variant 2: A hybrid courtyard house with up to two floors on the ground level, paired with a separate apartment featuring a rooftop terrace above. Both units can function as either owner-occupied or rental apartments.

Variant 3: A combination of a single-story courtyard house on the ground floor and a maisonette apartment with a rooftop terrace on the upper levels, offering a balance between privacy and shared outdoor spaces.

Variant 4: A mix of three independent residential units. The ground floor is designed as a courtyard house, while the upper floors consist of separate apartments, each with its own defined spatial hierarchy.

These four variants highlight the flexibility, efficiency, and adaptability of the proposed housing model. To ensure its successful implementation, the project follows a structured yet participatory development approach aligning with Hamdi’s (2010) concept of “incremental housing” that evolves organically with its residents.

The structural core of the house (load-bearing elements, roof, and access core with an internal staircase) is standardized and constructed by the municipal authority to establish a cohesive urban fabric. Future residents are given the opportunity to construct external walls, install windows, and configure the internal layout according to their specific needs and preferences. This approach resonates with Piqueras and Cabrera (2024), who trace the evolution of prefabricated housing as a strategy for flexible, incremental, and socially adaptable building. This allows them to embed their personal identity into their living spaces.

This approach offers several key advantages. First, it ensures compliance with essential safety standards in house construction, both in terms of structural integrity and execution. Second, it is more cost-effective for future residents, as they are relieved of the financial burden of building the basic structure. This cost efficiency also helps prevent potential conflicts between residents and municipal authorities, discourages illegal construction, regulates building density and living space, and curbs speculation on private property.

Each residential unit benefits from direct and separate access from the street, a feature that enhances user acceptance and fosters a sense of individuality, making each apartment feel like a distinct and independent home. Furthermore, the spatial system of the buildings is carefully integrated with surrounding open or green spaces to create a rich and livable environment. Each apartment is equipped with a generously sized private outdoor area shielded from street view. Ground-floor residents enjoy a close connection to nature, while those in mid-rise levels have access to hanging terraces oriented in different directions to preserve privacy and avoid overlooking neighboring outdoor spaces.

Now the question arises: why is it worth investing in the proposed model? To highlight the advantages of this solution compared to the old model, it is useful to compare it with the previous housing model in the design area. This shows how the new model combines traditional building elements with innovative ideas and which additional improvements make it particularly suitable.

As Lynch (1960) emphasized, urban form plays a crucial role in shaping people’s emotional connection to place, which makes the retention of traditional spatial characteristics essential in post-war reconstruction. Therefore, the closely built houses with narrow alleys and pathways in the new model reflect the historic urban fabric of pre-war Aleppo. By incorporating these elements, the new settlement preserves a tangible link to its past while simultaneously embracing a renewed, modern identity.

Furthermore, traditionally, multiple generations or extended family members often lived along the same street. The proposed model reintroduces this form of social organization through shared residential clusters. While the concept remains rooted in traditional patterns, it is adapted to contemporary needs and lifestyles. In doing so, this model supports intergenerational living and community resilience elements identified by Dovey (2010) as critical to socially sustainable urbanism. Additionally, it mirrors efforts such as the revaluation of the traditional barraca in Valencia, Spain, where vernacular housing forms were modernized without erasing their cultural significance (Marcel·lí Rosaleny Gamón, 2021).

Moreover, as Koolhaas et al. (2018) observe, architectural elements such as courtyards and terraces serve purposes beyond spatial organization: they shape daily life and reinforce identity, especially in post-crisis contexts. In this approach, key features of traditional homes like internal courtyards and rooftop terraces are preserved but reinterpreted in a more structured and cost-effective manner. This integration of heritage values with contemporary architectural principles enhances livability while maintaining cultural continuity. Courtyard designs, long valued for their climatic responsiveness and social functionality (Sibley et al., 2004), continue to offer significant benefits, particularly in dense, low-income environments.

Finally, the proposed model allows for flexible spatial subdivision and adaptable family arrangements. This aligns with Karle’s (2021) vision of responsive housing systems that respect existing typologies while enabling densification and modernization. Moreover, this adaptive design logic echoes the “open building” approach discussed by Habraken (1999), which promotes long-term usability, local customization, and social resilience.

8. Conclusion

This research emphasizes the central role of collective memory in the restoration of Aleppo’s informal neighborhoods. It argues that post-conflict reconstruction must go beyond rebuilding infrastructure to also preserve identity, cultural heritage, and community continuity. Rather than relying on generic housing models, the article proposes a hybrid approach that integrates traditional architectural forms with innovative, context-sensitive urban solutions.

The proposed model advocates for socially inclusive, community-driven design empowering residents not only to reclaim their homes but also to recover their cultural identities. Participatory in nature, this approach builds on the perspectives of Halbwachs, Bevan, Till, and others discussed earlier, ensuring its social and cultural foundations remain firmly grounded in established theoretical frameworks.

In post-war Aleppo, architectural interventions must therefore transcend the technical and spatial; they must fulfill ethical responsibilities to mend, preserve, and reinterpret the cultural narratives embedded in the built environment. Rebuilding, in this sense, is not merely about home-making it is about re-weaving the social and symbolic fabric of the city.