1. Introduction

In the 18th and 19th centuries the city of Glasgow grew rich off the profits generated by plantations of tobacco, sugar and cotton cultivated by enslaved people on stolen land. This new wealth resulted in a population boom of workers flooding the ‘second city of the Empire’ to support its burgeoning industries and began to show itself in the city’s architecture. Many merchants, members of the aristocracy, bankers and Lord Provosts (an office equivalent to a Lord Mayor) in Glasgow invested in this lucrative trade and used the returns to build commercial buildings, banks, private mansions and civic buildings and monuments.

More often than not, these buildings are designed in the classical style. Their large number exemplifies the full range of this aesthetic, from Palladian to Italianate to Edwardian Baroque to Greek Revival, and their grand facades tend to be uniformly dotted with columns that are more decorative than structural. Here, as in so many European cities where this style once dominated, the column’s function has arguably been subsumed by its form. It can now be seen as a signifier or shorthand for power, whiteness, patriarchy and wealth.

In this paper I will focus on George Square, Glasgow’s primary ‘civic’ space, originally laid out in 1782, to consider how the column enacts patterns of nostalgia and inequity through the facades of the City Chambers and the Merchants House, and the Walter Scott Monument. Two out of three of these structures were built after the full abolition of slavery in the UK but, I would argue, are still closely linked to Glasgow’s colonial period, emerging as they do at the height of the British Empire which continued to expand, building on this legacy of injustice and extraction of both human labour and natural resources, into the late 19th and early 20th century. As well as looking at these forms of classical architecture I will examine the vegetal origins of the column in order to consider the relationship between colonialism and the climate crisis (IPCC, 2022) in a new light. I argue that by drawing on the column’s origins in plant life, the form can be reimagined as an urgent warning of the need for climate justice in this moment.

The injustices of the climate crisis require us to turn our gaze to the future as well as keeping hold of the past. This Janus-like position reminds us that memory and imagination are closely related. Both functions originate in the hippocampus – in evolutionary terms, you need to draw on past experiences in order to fabricate the images that allow you to predict what might happen next. You have to remember the past in order to imagine the future. In this paper I want to hold these two states together, in order to look forward as well as back, in order to map time as well as space (See also Rego, 2024). This aligns with my primary method of site-writing, which Jane Rendell defines as a ‘critical and ethical spatial practice’, where sites can be ‘remembered, dreamed and imagined’ as well as material and political (Rendell, 2019) as well as Saidiya Hartman’s process of ‘critical fabulation’ (Hartman, 2019). This is folded within a wider methodology of ‘ecological writing’ that allows my research to examine the relations between many different fields and disciplines as well as sites and temporalities.

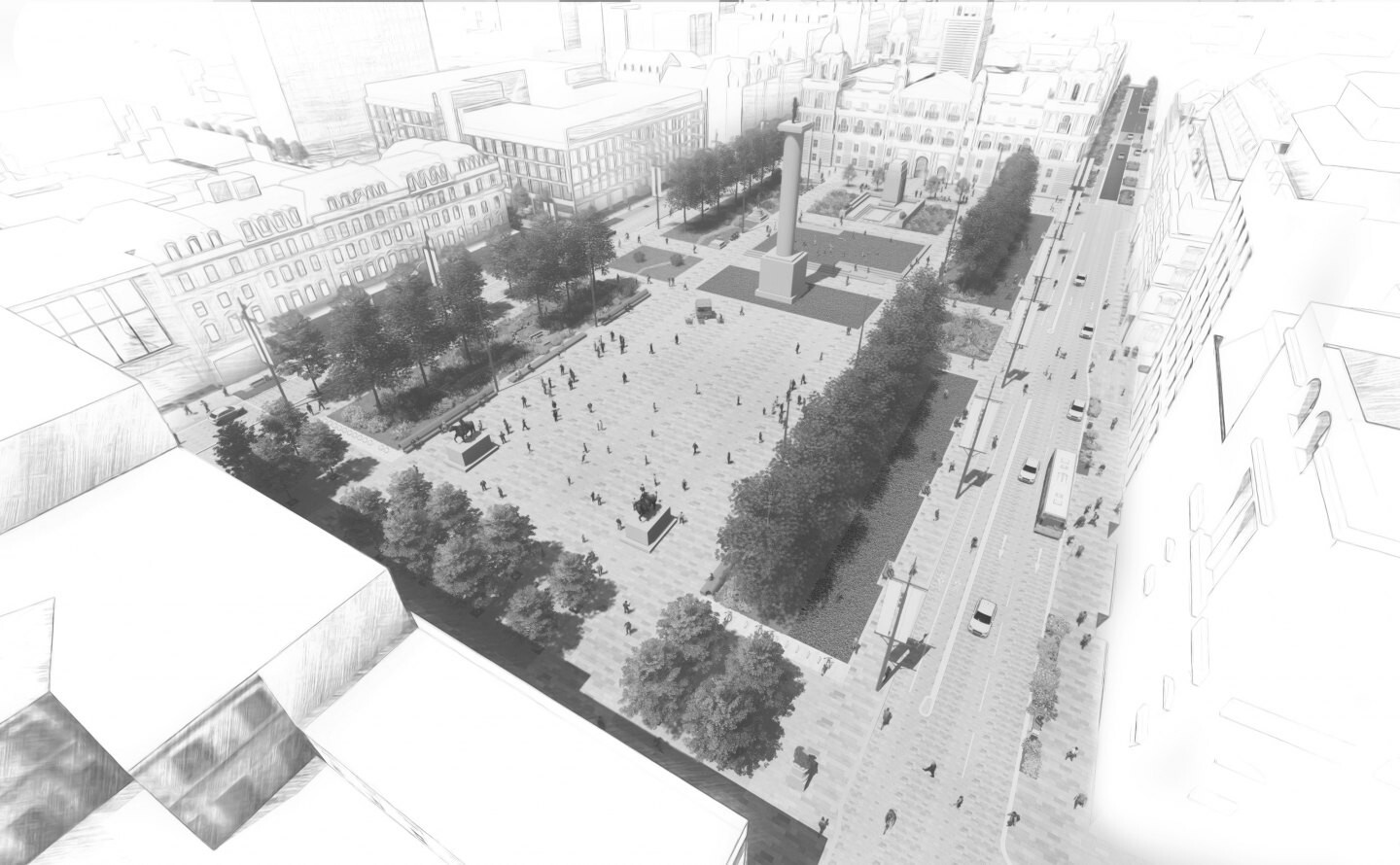

George Square is caught between memory and imagination. Currently being redeveloped as part of Glasgow City Council’s £115 million ‘Avenues’ project – a response to the climate crisis which aims to create ‘Safer Streets, Greener Spaces and Better Connections’ (Overview, n.d.) – and yet still steeped in colonial and imperial histories that are not explicitly declared or memorialised. Spanning the whole of its eastern side is the town hall – known as the City Chambers – completed in 1888, at the height of the British Empire. In the middle of the square is a freestanding column built in 1837 and topped with the figure of Walter Scott, one of the many statues of wealthy white men that adorn the space, and often adopted as a prominent position from which to hang banners or wave flags during the frequent protests that happen here. Lastly, on the western side of the square is the Merchants House, a building that dates to 1874 and testifies to Glasgow’s links to triangular trade with its motto, Toties redeuntes eodem (‘So often returning to the same place’). By briefly describing these three sites I hope to examine how a colonial past can be memorialised through looking forward as well as looking back, and to suggest that the column can become a reminder that the natural world and our part in it is the place we, in the Global North, must learn to return to, if we are to avoid further climate catastrophe.

2. The square as a ‘site of memory’

The close links between memory and imagination can often be problematic. Where there is recollection there is also invention. Memory becomes ‘vulnerable to manipulation and appropriation’ (Nora, 1989, p. 8) and nostalgia creeps in. Crystallised into history, memory remains ‘incomplete’ and yet claims ‘universal authority’ (Nora, 1989, p. 9). In George Square, Glasgow’s colonial past lives on through the pomp and splendour of its architecture. Despite numerous calls for memorialisation since (at least) the Black Lives Matter uprising in 2020, no signs, monuments or museums testify to the city’s role in the trafficking of human beings and the expropriation of land as part of the colonial project. An uninformed visitor to George Square would be forgiven for thinking the city was still proud of this history.

The square can be seen as what Pierre Nora terms a lieu de memoir, a site of memory, fixed in its narration of history, rigid in its order and its need for ‘commemorative vigilance’ (Nora, 1989, p. 12). This vigilance manifests itself in the frequency with which the City Chambers is used as a backdrop for commercial events and promotional photographs (McGillivray et al., 2022, p. 63), cementing the image of Imperial grandeur and exploitation ever further. This translates even to the current plans for redevelopment where ‘Tree position should allow for important vistas to impressive architecture and/or businesses surrounding the Square’ (Overview, n.d.), despite this requirement being rarely mentioned in the public consultation about the new design. This shows that while the city may not profit from the colonies anymore, its reliance on cultural capital from this period remains and its need to ‘buttress’ its identity remains strong (Nora, 1989, p. 12). As well as glorifying an inglorious past the imposing buildings around the square continue to act as signifiers of domination and hegemony on passersby through their height and ornate decoration. The square is described as the ‘city’s living room’ (Overview, n.d.) but there are rarely more people here than birds, rarely spontaneous social gatherings as opposed to commercial events or organised protests.

3. The City Chambers

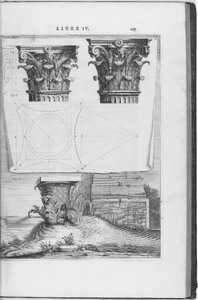

The City Chambers were designed in the classical style by architect William Young. Taking his main inspiration for the facade from Rome, he modelled his second-storey Corinthian columns on those of the Jupiter Stator temple. Here the architecture serves to evoke a false memory of ancient splendour – even the untrained eye immediately associates columns with antiquity. The choice of three arched doorways, modelled on the Arch of Constantine locates us more specifically to Rome, which was, of course, head of its own globe-spanning empire built on chattel and other forms of slavery (though not based on race).

Another clear nod to ancient civilisations and the might of empire lies in the building’s pediment, which was originally supposed to show a representation of Glasgow with the Clyde at her feet, ‘sending her manufactures and arts to all the world’ (Young, 1885, p. 143). However the design changed to mark Queen Victoria’s jubilee in 1887 and became a sculptural group depicting the monarch with representations of England, Scotland, Ireland and Wales on her right while on her other side is a procession of figures representing India, Africa and other colonial subjects. As historian Stephen Mullen has written, ‘The positioning of several figures was intended to symbolise the nature of the relationship between metropole and colony.’ (Mullen, 2022, p. 48) The subjects’ place in the hierarchy is made clear by their positioning on the monarch’s left, and the fact that the men representing India and Africa appear to be physically guided towards the queen – as if alluding to the colonial project’s ‘civilising mission’ (Groten, 2022, p. 114). Above the pediment stand three idealised figures symbolising Truth, Riches and Honour which amplify the composition’s proud message.

The laying of the foundation stone on 6 October 1883 was accompanied by a grand ceremony. A public holiday was declared and 600,000 people poured into the square for the spectacle. Lord Provost John Ure declared that the act marked ‘the commencement of an undertaking which we hope will last as a memorial to many generations of the greatness and prosperity to which Glasgow has attained at this present day.’ (Young, 1885, p. 58). The building was completed six years later and was inaugurated by Queen Victoria herself. Speaking at this event the new provost, James King, hoped that the new town hall would ‘promote with zeal and perseverance the highest and best interests of this great community and of the empire to which it belongs.’ (Groten, 2021). On both occasions we can see that the city’s prosperity and its role in the empire become embedded in the stones of the building, turning it into a giant monument to imperial domination, and a decided act of ‘commemorative vigilance’.

4. The Merchants House

On the opposite side of the square to the City Chambers and occupying its north western corner is the Merchants House, designed by John Burnet and opened in 1874 as Glasgow’s Chamber of Commerce. Its top two storeys, featuring plain columns with swagged ionic capitals were added in 1907–09. The building’s domed tower features a finial of a ship sailing atop a globe to emphasise the reach of Glasgow’s trading power, its prow pointing west. As with the city chambers, there is no signage on the building’s exterior to directly memorialise the role of slavery and colonialism in the attainment of the city’s, and the merchants’, wealth. There is only a plaque inside the building, not usually open to the public, recognising ‘the benevolence of a wide range of individuals’ with the ‘awareness that some of our donors in the 18th and early 19th century profited from slavery.’ An oblique memorial to the human cost of trade, can perhaps be found on the facade in the form of the six male and female caryatids on the ground floor who support three oriel windows, their bodies truncated by large crests depicting merchant ships and the heraldic lion rampant.

The building’s five storeys and the fact that it is part of the same block that once housed the Bank of Scotland and its chambers – an institution equally embroiled in the brutality of transatlantic slavery – mean it is more than capable of matching the facade of the City Chambers in its ability to dominate the civic space and impose its message of grandeur on the passerby. No doubt the merchants’ philanthropy did much good in the city but then, just as now, this kind of activity became the dominant message, overshadowing the origins of the money to fund it.

5. The Walter Scott Monument

Built in 1837, a year before the emancipation of enslaved people in Britain’s colonies, the Walter Scott Memorial Column was the first monument to the Scottish writer to be built and stands as a classical counterpart to the more famous gothic memorial in Edinburgh. The fluted column sits on a square base decorated with lion masks and acts as a giant pedestal for an over lifesize statue of Scott who is wrapped in a plaid and looks down on the square below. The column he stands on dominates the centre of the square acting as a giant sundial and as another clear sign of the city’s alignment with the classical style, whose harmony and symmetry could be seen as a mask for the disorder of the violent colonial project. Scott is one of ten statues of white men in the square; the equestrian statue of Queen Victoria is the only one that depicts a woman. As well as enforcing patriarchal norms, the statues comprise at least three men who had direct links to slavery through their role in parliament, the British army, trafficking and through inherited wealth. While I do not wish to enter the debate about Scott’s opinions on the slave trade here, I think it is worth noting that the celebration of him as an aristocratic white man continues to act as a legacy of the patriarchal colonial project, the great height at which he is positioned enforcing hierarchies of race, gender and class.

6. Sites of imagination

The three sites briefly described above play an important role in George Square’s function as a site of memory. However I want to turn now to their potential as sites of imagination, examining how their message of domination has been subverted with their use in contemporary gatherings in the square and how the form of the column can become a new kind of monument for our uncertain present.

I first became aware of the potential for subversion of the site’s grandeur at a climate strike in 2019 when thousands gathered in Kelvingrove Park in the West End and walked through the city centre to George Square. It was a warm day in late September and upon reaching the endpoint protesters quickly began to fill the sterile green lawns and municipal benches surrounding the Walter Scott column as well as sitting on the tarmac of the square, holding placards that were both rageful and ironic. The sheer number brought together by this cause felt like a dent in the usual power of the statues and the facades around the square to dominate this space.

I was reminded of the power of the crowd to transform space at the first Pro-Palestine demonstration at the beginning of Israel’s latest siege of Gaza. The square was filled once again and this time the Walter Scott monument took centre stage as a group of teenagers scaled the base of the column and began waving Palestinian flags and setting off green and red flares. Unlike the citizens that gathered for the ceremony commemorating the laying of the foundation stone of the City Chambers, who were praised for their good behaviour (Young, 1885, p. 45), this group was unruly and disparate, united by their calls for solidarity in the face of this contemporary form of colonialism.

The square has been filled with pro-Palestine demonstrations many times since then. Here the site of memory allows each gathering to feel like an echo of famous demonstrations such as that of 1908 when hundreds of protestors entered the City Chambers singing ‘The Red Flag’ in protest against unemployment or one of the most famous episodes in the Red Clydeside history, the Battle for George Square in 1919, in which workers demonstrating to reduce the working week from 54 hours to 40 hours, were baton charged by the police. Over the last century the square has also hosted celebrations to mark the end of the second world war; independence rallies; numerous other demonstrations including those in support of Ukraine and disability and trans rights; and even Nelson Mandela who came to accept the freedom of the city in 1993. Of course, the square has also been used as a site of protest and celebration by TERFs, anti-vaxxers and the notorious Rangers FC fans and I do not wish to romanticise all forms of protest but nonetheless these were crowds of ‘ordinary’ people claiming the space as their own.

I want to stay with those acts of protest that used this space to collectively imagine a world that is anti-capitalist, anti-discriminatory, anti-colonial and anti-imperialist. Each of these gatherings, though small compared to similar demonstrations in global capitals, work to wear away some of the memory of grandeur held in the architecture and by extension the larger systems sustained by such monuments. They help to reinscribe, even if only temporarily, the story told by the site. In these moments we are required to think ‘as part and as crowd’ (Glissant, 1997, p. 9), to place ourselves in a larger story. Just as imagination uses the threads of memory to create a picture of something new, many of the protesters – whether for climate, Palestine or Ukraine – recognise the need to acknowledge past injustices in the path to future reparations. The space of protest is apt for envisioning how we can hold memory and imagination at once – often we are coming together to say never again and to demand something better.

7. Column as tree

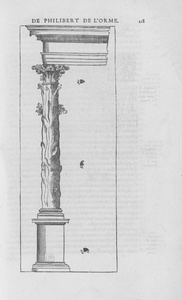

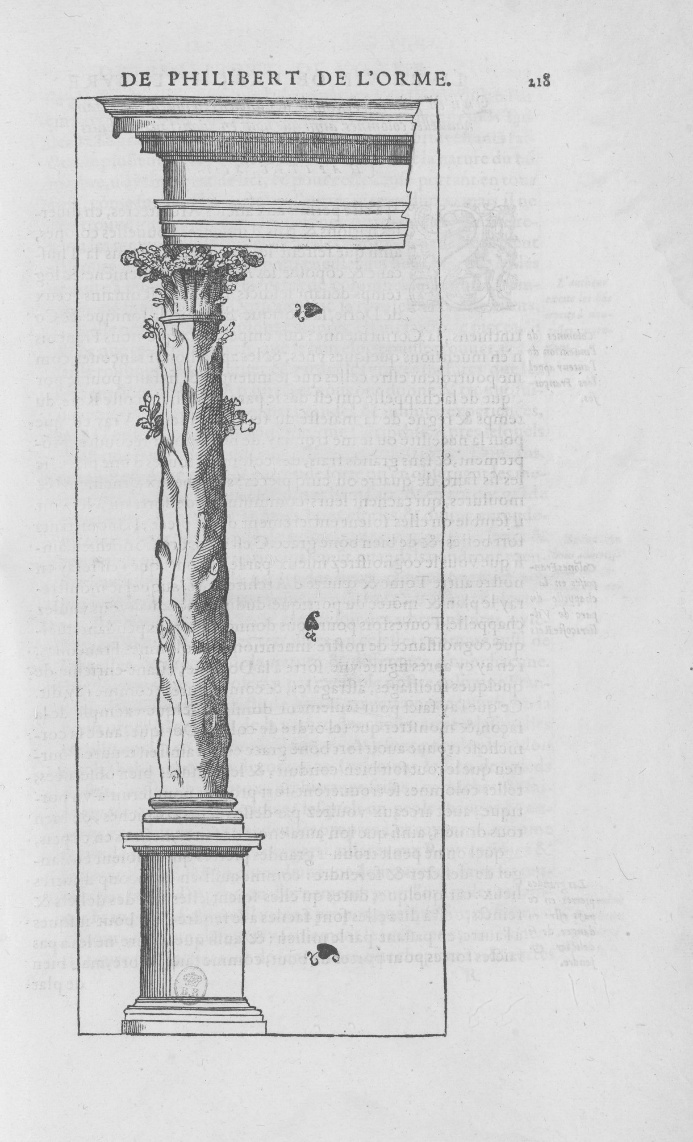

I’d like to turn now to the form of the column, whose origins lie in the trees used to build the first temples. As technology developed, along with the desire to make these more permanent, wooden posts were replaced by stone and yet the vegetal form remained as a schematisation. The first columns were developed by the ancient Egyptians and were directly stylised to look like bundles of reeds. In the Greek and Roman versions, the fillets and flutes of the Doric form recall the fissures of bark; the Corinthian and Composite order are defined by their inclusion of acanthus leaves; and the volutes of the Ionic order, though mostly associated with ram horns may also be linked to Egyptian lotus motifs (Small, 2001). Each column therefore acts as a reminder of the plant life that sustains our existence on this planet. Each column has the potential to be seen as a tree again, no longer singular and sterile but branching out in a network of mutual aid.

Taking the Latin root of the word ‘monument’, monere, meaning to warn or advise, I want to imagine every column in George Square as a marker not just of the past but of what’s to come. As well as recalling the city’s colonial history they could look forward to its ecological future, turning nostalgia and memory into imagination and action. As anthropologist Nicholas Thomas notes, 'colonialism has always been ‘imagined and energised through signs, metaphors and narratives’ (1994, p.2). Now it is time to reimagine and adopt these signs to make evident the links between this period in Scotland’s past and the environmental crisis of which we are only just seeing the beginning.

The men who commissioned these buildings had no trouble looking forward, imagining their city’s legacy to remain untarnished for a century to come. In the Lord Provost John Ure’s speech during the laying of the foundation stone of the City Chambers he said that ‘Its massive walls, its lofty roof, its spaciousness, its beauty will, I trust, be regarded as emblematic of the resolution and courage, the high aspirations, the magnanimity, and the purity which shall more and more become the goal of the citizens’ striving.’ (Young, 1885, p. 60). But more and more it feels like we are stuck looking back, our civic space reinforcing a message of pride rather than encouraging the repair that is needed in both the struggle for social and climate justice. Colonialism lives on in the ongoing threats to Ukraine, Palestine and even Trump’s suggestion of annexing Greenland, but most of all in the ‘imperial mode of living’ (Brand & Wissen, 2021, p. 4) demonstrated by the acts of extraction and exploitation carried out on poorer countries for the benefit of wealthier countries, and the disproportionate effects of the climate crisis affecting the Global South. Perhaps now it is time to call on George Square to become a site of what David C. Harvey calls ‘prospective memory’ – a process he describes as ‘unfolding and ongoing relationship between past, present and future’ (2013 as cited in Storm, 2021, p. 60) – in order to resist inertia.

The natural world is not to be romanticised of course, while trees offer a helpful metaphor for mutual aid, not all ecological relationships are benign. The behaviour of the more than human which is often just as self-serving as our own species and only unconsciously contributing to a balanced ecosystem. The plant I have been thinking most closely with because of its fluted stem, the giant hogweed, is considered to be an ‘invasive’ species and its sap can seriously burn human skin. As Vittoria de Palma writes, nature’s ability to be both life-sustaining and destructive presents us with a paradox, but one that is ‘productive’ (2006) in its ability to introduce complexities that will help us in the struggle for climate justice.

Similarly, it is important to bear in mind the far-right’s appropriation of classical imagery as part of its narrative of white supremacy in Europe. Following Mussolini’s example, neo-fascists are still adopting the symbols and architecture of ancient Rome for its striking imagery – such as the bundle of rods known as the fasces from which the word fascism takes root – and as a way of legitimising their movement (Bond, 2018). At the same time, on his first day in office, President Trump issued a memorandum calling for federal buildings to ‘respect regional, traditional, and classical architectural heritage’ (Pontone, 2025), recalling his 2020 ordinance that federal buildings should be built in the ‘classical’ style. While celebrating the potential of the column to become a symbol for climate justice, I am wary of these connotations and the danger in reproducing this symbol without the critical context needed to undermine its power.

It may seem whimsical or flippant to suggest we reimagine columns as trees but the act of imagining has always been necessary to the colonial project which would not have emerged, as Edward Said reminds us, ‘without important philosophical and imaginative processes at work in the production…acquisition, subordination and settlement of space’ (1989, p.218). Imagination also allows us to conceive of better worlds – it is imagination that allowed George Square to temporarily become George Floyd Square, that allowed thousands of people to flood the streets to demand climate justice. As the Palestinian poet Zaina Alsous writes, the speculative is a language that allows ‘our minds [to] wander toward the what-if and undo the bounds of the colonial structures we have learned and existed under for so long’ (Farah, 2024).

While speculation and imagination sow the seeds of a shift in perspective that is yet to fully take hold, concrete actions are transforming the square already. Housed in the former site of the Bank of Scotland chambers – a building which sits next door to the Merchants House and whose piano nobile windows are framed by Corinthian columns – is Refuweegee, a charity that provides ‘a warm welcome to forcibly displaced people arriving in Glasgow’ (n.d.). Where once columns stood as a ne plus ultra, as gatekeepers for buildings designed for the wealthy and white, their symbolism is undermined in this welcoming space. The view from the Refuweegee prayer room looks out over the whole expanse of George Square towards the city chambers. As the world warms and climate refugees become ever more numerous, spaces like these will be even more necessary. If the most sustainable building is an existing one then, it is fitting that these buildings be repurposed in this reparative way (See Cabrera-i-Fausto & Perna, 2023, for more on durability). Though originally designed to project a message of power and wealth for centuries to come, now they can be reimagined for the other world that is possible, and offer shelter and comfort to those who cannot enjoy the luxury of permanence, those who remain excluded and oppressed by the racist legacies of colonialism.

There are 60 columns on the west facing facade of the City Chambers. There are eight trees in George Square. The new development promises to increase this to 40 and to add sensory planting and rain gardens as well as ornamental shrubs and lawns. This is all welcome news, though judging by the spindly trees and sparse beds installed in other parts of the city that have undergone the ‘Avenues’ makeover, it will be a while before the verdant vision of the artist impressions will be achieved. During a consultation with the public, the majority of the comments were focused on the area’s green spaces with many people ‘keen to see more planting in less formal arrangements, with native species and many more wild and biodiverse elements incorporated.’ (New Practice, 2022, p. 3) According to the consultation, the majority of respondents also ‘did not mind, or actively support, moving existing statues or replacing them with an alternative feature’ (ibid, p.5) such as a water fountain or space for contemporary art.

It is also important to note that 37% of people also suggested that the redevelopment is a waste of money and as a resident of Glasgow it’s easy to see how the funds behind this project could be better spent on social housing, de-privatising the city’s overpriced bus networks and upgrading residential streets, rather than a square mostly used for touristic and commercial purposes (when not a site of protest). Not to mention the fact that in order for these works to take place this public space will be closed to visitors and protestors until late 2026.

We are used to seeing and not seeing the vines, fruits, waves, leaves and lions in the spandrels, cornices and festoons that adorn our historic built environment, we have become inured to columns beyond their ability to act as shorthand for classical ideals. But, as James Baldwin said, ‘The world changes according to the way people see it, and if you alter, even by a millimeter, the way a person looks or people look at reality, then you can change it’ (Romano, 1979). Perhaps imagination can play a role in shifting our consciousness of these signs of wealth and in turn, pave the way for the larger shifts needed to ensure our public spaces become porous and not fixed (Rancière, 2023), to decentre the human and to see the natural world as more than just background and ornament, before further tipping points are reached.