1. A Heterotopy in the city and upon the Rock

''The conclusion is that things, particularly stones, remain silent, yet at the same time they speak. Hence, it may be concluded that these are materialized and eloquent silences."

Histories of Silence (Corbin, 2019, p. 38).

A subtle thread connects Aurelio Galfetti’s restoration work at Castelgrande with one of the most prominent theories in twentieth century “place” philosophy (Casey, 1998). In one of the project’s first international publications (Galfetti, 1986b) – an article dedicated to two of his most recent architectural projects: the restoration of the postal building and that of Castelgrande – the text was preceded by Michel Foucault’s renowned essay Of Other Spaces (Foucault, 1986). It is no coincidence that Pierluigi Nicolin (Nicolin, 1986), editor of the journal, chose to establish this association, as Galfetti’s projects shaped an “other space” – in the Foucauldian sense – where the historical, the natural, and the urban intertwine within a critical and simultaneous space.

In the article, through photographs by Stefania Beretta and Giovanini Chiaramonte, the site is portrayed as a landscape in metamorphosis. In the main image, the plasticity of the fortified walls, the vertical profile of the Bianca and Nera towers, the scaffolding still present in the urban space, and the solitary crane in the Internal Court, all reveal a space in transformation.

This photograph, taken by S. Beretta five years after the project’s inception and reproduced in various publications throughout the progress of the work, is laden with meaning. Just like the perspective of Mathaus Merian in his Helvetia Orientalis (Merian, 1654) or J.M.W. Turner’s sketches during his journey through Bellinzona in the eighteenth century, the image transcends its documentary function (FIG. 1). Its vision positions us before a new dialectical event between the city of Bellinzona and its primary geological feature, the hill of San Michele. The urban space , depicted as a true heterotopia of overlapping times, narrates – as Galfetti himself notes – that the “rock” is simultaneously “a great stone that survived the ice that once filled the valley; a promontory once inhabited, isolated as a fortress in the middle of the valley, which used to be a river and swamp; a defensive structure that once dominated the city.” (Galfetti, 1991, p. 30)

In this sense, memory is employed as a design mechanism capable of transforming our present perception of space (Rego, 2024). This article seeks to structurally examine the design strategies developed by Aurelio Galfetti. The goal is to place them within a broader theoretical framework that allows for their individual analysis and contributes to a deeper reflection on the role of architecture as a mediator between memory, matter, and time.

2. The Semantic Mutation of Place

The articulation of the void as a critical-spatial tool for the historical dimension

“For me, history is the sum of all possible histories – a set of multiple skills and points of view, those of yesterday, today, and tomorrow. The only mistake, in my view, would be to choose one of these histories to the exclusion of all the others.”

The longue durée (Braudel & Wallerstein, 2009, p. 182)

Undoubtedly, the ensemble formed by the hill of San Michele and the Castelgrande fortress constitutes one of those complex and unique places where one can reconnect not only with the longue durée of the past, but also with a contemporary vision of heritage and landscape. Thanks to the architectural poetics of Aurelio Galfetti – who has managed to interpret the chaotic and elusive reality of our time – the fortress stands as a paradigmatic example of contemporary restoration.

Throughout its history, as a reflection of the political, social, and cultural changes in the Canton of Ticino, the Castelgrande fortress has served to signify the evolution of the territory. Its strategic character as the “gateway to the valley” – as described by historians from different periods such as J. Rahn (Rahn, 1894) or W. Meyer (Meyer, 1993) – has been redefined over time, evidencing a long and complex history with multiple phases of occupation, construction, and transformation. As Galfetti points out, the diversity of names it has received – Magnum or Vecchio in the Middle Ages, Castello di Uri or Castello di San Michele in the 19th and 20th centuries – reveals this evolution (Galfetti et al., 2006a, p. 205).

But before properly understanding the contemporary restoration, it is necessary to briefly mention two key episodes that, although opposite in intention, profoundly altered the meaning of Castelgrande.

From the mid-19th century onwards, the fortress underwent a particularly intense phase of transformation. After its use as a prison and subsequent abandonment, its first major transformation occurred around 1850, when it was converted into an arsenal. This new function involved the construction of access for vehicles and buildings with gabled roofs, introducing civilian elements that significantly altered its defensive structure. This new identity of the monument led the Cantonal Government to initiate, in 1953 – on the occasion of the 150th anniversary of the Canton of Ticino – a restoration aimed at recovering the symbolic value of the castle. Entrusted to architect Max Alioth, the project consisted in demolishing the civilian additions and reconstructing historical elements in style, with the objective of “returning the castle to how it had been from 1500 to 1800” (Alioth, 1955, p. 92). However, despite the institutional effort, the operation responded to a historicist logic lacking critical rigor and failed to reintegrate the fortress into urban life, which continued to perceive it as an isolated object.

At the beginning of the 1980s, after a series of attempts to recover the monument, a new phase began under the direction of architect Aurelio Galfetti. Unlike previous approaches, this contemporary restoration started with a clear urban and social objective: integrating the monument into the life of the city (Galfetti et al., 2006b). For this purpose, the Cantonal Heritage Commission proposed restoring the fortress to host a museum dedicated to the history of the city, using the existing buildings without major additions. Furthermore, as a fundamental condition, it was required to improve accessibility to the hill by building an elevator that would directly connect the urban center with the fortress.

In this context, and drawing primarily on the theoretical contributions of Andrea Bruno and Paul Chemetov as well as on the idea of the project as a critical tool for interpreting context, present also in the works of Tita Carloni and Vittorio Gregotti, Galfetti steered the Castelgrande project toward a continuous dialogue between the conservation of the monument and its necessary transformation in response to the needs of contemporary society. This tension between permanence and change, already identified by Victor Horta at the 1931 Athens Conference (Hernández León, 1997), becomes the conceptual axis of his project. Under the motto Conserve = Transform (Galfetti, 1986a), Galfetti does not approach restoration as a formal or stylistic reconstruction, but rather as a process of re-signifying the place. His proposal begins with a deep semantic shift: to transform the fortress into an urban park, into a dialogic space where the multiple memories that have shaped the site over time may converge (Privitera, 2017). As Galfetti himself explains:

‘‘But to transform what? Evidently not the monumental parts, not the volumes, but the voids – what lies between things. That is, the relationship between things. To transform the space once used for defense, for imprisonment and many other such purposes, into a space that welcomes and brings people together: that was, in my opinion, the challenge to face. To transform a place of defense into a place of encounter, into a park: the park of the city of Bellinzona.’’ (Galfetti, 2009, p. 35)

In contrast with previous restoration efforts, which enhanced the value of the monument from an aesthetic perspective, Galfetti’s project relies on the void as the catalyst of the site’s values. While the longue durée serves as a narrative thread to reflect on permanence and to guide the critical restoration of the pre-existing buildings, the critical-spatial reading of the place and the program proposed by the Commission become the project’s foundational tools for transforming its meaning.

Although in practice the project involved the critical restoration of existing structures, it is through the work on the grassy surfaces that this approach is most clearly appreciated (Galfetti, 2016, p. 103). In line with M. Voyatzaki (Voyatzaki, 2016), this operation can be understood as a balance between permanence and adaptability, conceiving architecture as a mutable entity in constant interaction with the social, the urban, and the historical.

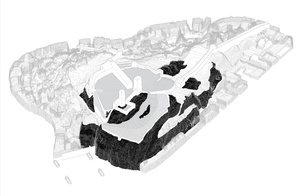

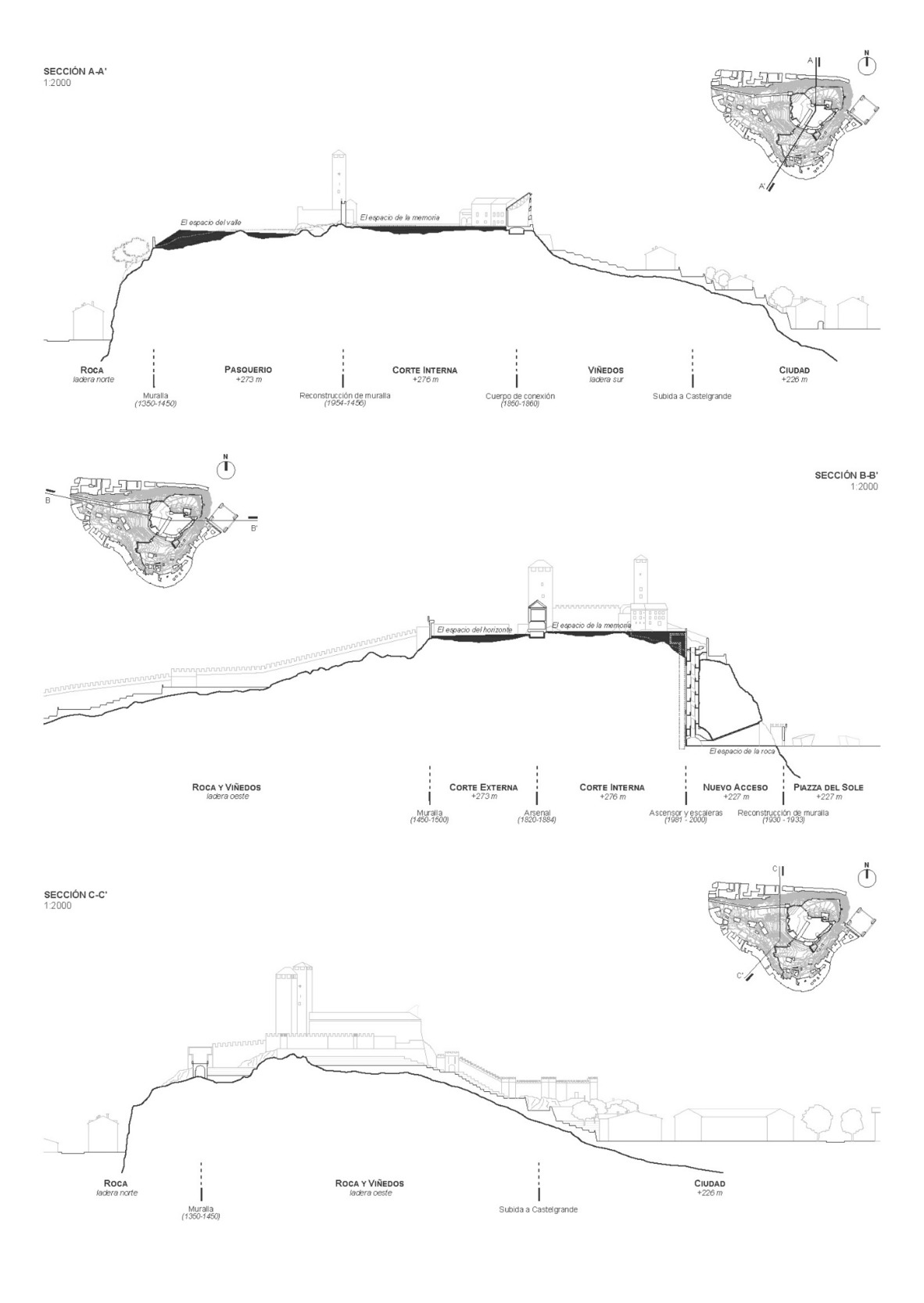

In this sense, the sectional representation becomes the most effective method for openly analyzing this design strategy (FIG. 2). However, it is striking that, despite the relevance of the new topography, it is often ambiguously represented in many publications – depicted either as an undifferentiated black mass or reduced to a mere outer profile. This omission is not inconsequential, as it prevents the recognition of the new topography’s role as an articulating device between the existing architecture, the urban landscape, and the site’s geological structure.

To clarify this relationship, the geological profile of the hill has been incorporated into the architectural sections. This profile, developed by Pier Angelo Donati, has served to document and understand the extensive historical evolution not only of the settlement but also of the territory (Donati, 1986). In this way, by juxtaposing the new topographical profile with the geological one, the construction of the ground plane emerges as the main architectural tool for establishing a new dialogue between the different temporal layers that shape the fortress.

Thus, the topographical transformation becomes the primary strategy for projecting the landscape, as well as an effective tool for redefining the relationships between architecture, nature, and memory (Rodríguez Fernández, 2019, p. 17). Following a fundamental architectural practice, the irregular surfaces of the spaces that organize the fortress – the Internal Court, the External Court, and the Pasquerio – are built to become fully defined surfaces where “the void, enhanced by the restoration project, did not prevail as consistently as it does today” (Galfetti et al., 2006a, p. 103).

Although the three enclosures are designed analogously, each one responds to specific objectives within the project and activates different readings of the architectural ensemble (FIG. 3). In the Internal Court, the incorporation of a retaining wall connected to the contemporary path allows the terrain to be shaped as a tapis vert – that is, a completely horizontal surface that redefines the space as a plaza where the different construction phases of the architectural ensemble are openly revealed. The External Court, designed similarly, becomes the stage for a critical restoration of previous historicist interventions and the recovery of the civil character of the space. In contrast, the the topographical transformation of the Pasquerio combines the creation of an inclined profile – which softens the view of the city – with the selective removal of terrain between the towers, allowing the underlying rock to become visible and thus activating a geological reading of the place.

As one moves through the spaces of the fortress, the landscape reveals itself as a place where the past is not simply preserved, but activated through spatial experience. As Michel Foucault states:

“The present epoch will perhaps be above all the epoch of space. We are in the epoch of simultaneity: we are in the epoch of juxtaposition, the epoch of the near and the far, of the side-by-side, of the dispersed. We are at a moment, I believe, when our experience of the world is less that of a long life developing through time than that of a network that connects points and intersects with its own skein.” (Foucault, 1986, p. 9)

Thus, “the park, as a space where the new coexists with the old” (Galfetti, 1991, p. 29), is conceived as a spatial structure that, by employing contingency as part of the design process (Romano & Perna, 2022), articulates the different historical and architectural phases of the site, becoming the true support where historical time becomes visible and confronts contemporary needs.

3. The Creation of an Artificial Nature.

The construction of the natural as a restorative tool for the urban and territorial dimensions

‘‘To examine a mountain range with curiosity, to understand the manner of its formation and the causes of its decay; to recognize the order that governed its rise, the conditions of its endurance and its resistance to atmospheric agents, to observe the chronology of its history is, on a larger scale, to undertake an analytical and methodical task akin to that of the architect and the archaeologist […] who form their deductions from the study of monuments.’’

Le massif du Mont Blanc (Viollet-Le-Duc, 1876, pp. 15–16)

While the previous section introduced topographical manipulation as the principal strategy for granting new meaning to the spaces within the fortress, this operation extends beyond the walled enclosure and results in a more comprehensive approach. The reshaping of the terrain is not limited to reorganizing existing architecture, but becomes the starting point for activating a territorial reading of the site.

During the course of the project, Galfetti identified in the transformation of natural elements a unique opportunity to recover a geological structure that, for more than six thousand years, has been intimately tied to both the historical understanding and the morphological evolution of the city itself. To use the words of Doreen Massey, we might affirm that in Galfetti’s critical interpretation of the place, geography matters (Massey, 2012). The space, shaped by medieval architecture and by the presence of the hill, is not merely a container of history but a dynamic phenomenon that has emerged through a constant confrontation among the social, the natural, and the material characteristics of the territory.

By imbuing the natural with a degree of artificiality, the projection of nature becomes a far more important endeavor than the valorization of other architectural aspects. In this process, the project uncovers, on each slope of the hill, an opportunity to bring forth the various memories of the place. The physiognomy of San Michele hill – conceived as the foundation of the park (Galfetti, 1991) and as a permanence that narrates the evolution of the territory (Rossi, 1977) – is capable of restoring the territorial scale of the ensemble while also allowing for the recovery of the settlement’s dual nature: civil on the southern slope and military on the northern one.

“In practice, we played with the profound nature of the Place, which over time was initially a rock and later a settlement submerged by vegetation and by human intervention (…) The interventions were carried out (…) on the elements (…), mineral or vegetal, with the goal of revealing their substance and reducing them to the purity of their nature, without going beyond them: the ‘cleaned’ rock dialogues with the wall, the designed greenery with nature.” (Galfetti et al., 2006a, p. 78)

To the south, where the rock is more schistose and softer (Donati, 1986), Galfetti proposes recovering the site’s agricultural tradition through the reconstruction of terraces and the reintroduction of vineyards. This operation is not merely a landscape gesture; it is conceived as a strategy for the cultural reconstruction of the territory. By restoring the agricultural profile of the slope, the project reestablishes continuity between the city and the fortress, consolidating a natural boundary that reinforces the civil character of the settlement in that direction.

On the northern slope, the design strategy takes on a radically different tone. Through a terrain manipulation operation based on subtraction, the project not only redefines the relationship between the castle and the urban fabric but also reconstructs its connection to the broader territory through a true act of landscape construction. Geological time – understood by Galfetti as "a hierarchically superior value to be rediscovered and promote’’ (Galfetti et al., 2006a, p. 110) – is incorporated into the monument through two complementary operations.

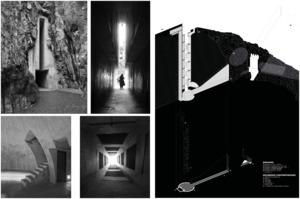

First, the complete removal of vegetation becomes a critical action that reactivates the geological materiality of the hill (FIG. 4). The rock, unveiled and exposed, assumes the role of a new façade for Castelgrande, functioning as a kind of mineral acropolis that links the monument with the urban dimension. This design gesture also serves as a metaphorical vehicle to express one of the client’s key aspirations. In Galfetti’s words, the goal was to “anchor the castle concretely and physically to the city, interpreting on a metaphorical level the client’s desire to insert it into urban life, almost fusing architecture and nature into a unified concept” (Galfetti et al., 2006a, p. 110).

Secondly, the functional need to incorporate an accessible path to resolve the 40-meter elevation difference between Piazza del Sole and the upper part of the Internal Court gives rise to a design that goes beyond mere utility. The vertical path cuts through the thickness of the hill, establishing a physical and symbolic connection between the man-made fortress and the natural fortress sculpted by glacial action more than twenty thousand years ago.

In line with the spatial strategies developed throughout the project, the creation of a promenade into the interior of the hill takes up the concept of the void as a structuring element. However, unlike previous operations – where the void was defined through the articulation of surfaces – here the void emerges through a strategy of direct subtraction from matter. This operation, conceived as an inhabited section carved into the geological mass, not only constructs a physical route between the city and the monument, but also becomes the most eloquent tool for building a truly dialectical landscape between the natural and the artificial.

The section of the route excavated into the hill (FIG. 5) not only illustrates the subtractive strategy as a design gesture, but also reveals how this operation generates a spatial structure deeply tied to Galfetti’s personal memory. The spatial sequence, defined in three moments – the grotto, the cunicolo, and the cavern, in Galfetti’s words – recalls a compositional logic associated with carved architecture, which the author had the chance to experience during his travels to Lycia (+xm plusform, 2008). While there is no explicit reference to the Treasury of Atreus, the tripartite organization of the route in Castelgrande bears a notable analogy to the spatial sequence of the Mycenaean tomb – dromos, stomion, and chamber – allowing for an interpretive link between both experiences.

Beyond any formal coincidence, the passage becomes a true dialectical landscape between the natural and the artificial. The flared reinforced concrete section acts as a contemporary rocky stratum, from which a dense and suggestive approach to the hill’s geological dimension is constructed. Its texture, altered by humidity, light, and the passage of time, allows the built matter to establish a visual and tactile dialogue with the rock, incorporating a contemporary sensitivity into the character of the place. Along the path, the visitor’s movement becomes a progressive immersion experience, in which the body engages with matter, shadow, and silence, intensifying the perception of the temporal depth inscribed in the territory.

Thus, space and time interweave in the composition of the architectural promenade, turning it into an exercise in architectural empathy (Einfühlung), where the body perceives and understands space before the mind (Garramone, 2013). This transference of bodily experience into space transforms architecture into a mediator of cultural and emotional meanings, converting a functional necessity into a spatial sequence in which architecture ceases to be an object and becomes a narrative.

4. The Metamorphosis of the Landscape

Spatial experience as an interpretive strategy of place

By way of conclusion, and based on the analysis carried out, we can assert that the restoration project of Castelgrande constitutes a complex and multifaceted project, full of nuances and, as Galfetti himself acknowledges, even accommodating contradiction (Galfetti et al., 2006a). As we have seen, the critical interpretation of the monument is not limited to the conservation and consolidation of what already exists but rather expands toward a broader vision that engages the city and the territory.

What might initially appear as a dichotomy between conservation and transformation is redirected toward a deeper interpretation of the context. The motto Conserve = Transform, employed by Aurelio Galfetti (Galfetti, 1986a), does not refer solely to the material alteration of the existing fabric; instead, it proposes its mutation through the experience of place. The way spaces are perceived becomes more significant than restoration itself. Although this work has not specifically addressed the restoration works made on the fortress buildings – such as the recovery of stone roofs or the à rasa pietra execution of the façades to reinforce urban continuity – it is essential to highlight that Galfetti’s critical restoration attends to all scales of the monument. Even the construction detail is conceived as a design tool capable of establishing an active dialogue with the context and contributing to the construction of a coherent landscape.

In relation to the objectives set out at the beginning of this article, it can be argued that the approach developed in Castelgrande represents a turning point in the author’s work, particularly in his ability to integrate architecture, city and territory. The relationship between the experience of space, the built environment, the urban fabric, and the territorial context, across multiple scales, is a constant in Aurelio Galfetti’s work (Galfetti, 2016, p. 37), yet in this case it is realised with exceptional intensity. Nevertheless, this project takes these strategies to a higher level of synthesis and radicality, extending the dialectic between the natural and the artificial towards the activation of memory as a design resource.

In this regard, Castelgrande transcends the disciplinary boundaries of restoration to integrate geography, urbanism, and architecture as essential components of the project. The relationship between built space, the urban, and the territorial – across multiple scales – is a constant in Aurelio Galfetti’s work (Galfetti, 2016, p. 37), but in this case, it materializes with particular intensity. Unlike earlier works such as the Rotalinti house (1961) or the public swimming pools of Bellinzona (1967–1970), where architecture confronts the landscape to construct place (Olavarrieta Acebo et al., 2023), in Castelgrande architecture is reduced to its essence: the manipulation of the terrain as the primary transformative tool of space.

In line with Iñaki Ábalos’s interpretation of Le Corbusier’s evolution (Abalos, 2022), which describes an abrupt shift from an architecture detached from the ground to one more deeply engaged with the material and spatial depths of the earth, Galfetti’s work can be understood as following an analogous trajectory.

Despite the limitations of this article, focused exclusively on the Castelgrande project, it can be anticipated that this work marks a turning point in Aurelio Galfetti’s career. From this project onwards, his architecture would evolve towards a conception of space rooted in topographical manipulation, turning the terrain itself into architectural material. Examples such as the roundabout project in Locarno (2000), the Aula Magna of the University of Lugano (2001), or the architect’s own house in Greece (2003) illustrate this approach. While other recurring strategies in his work would remain present – such as the pursuit of articulating architecture through a promenade or the transformative intent of turning function into space (Galfetti, 2001) – in this phase he would develop an authentic territorial architecture, in which the city and the territory become both the support and the material of the architectural project. All of this in search of what the architect himself defines as the essence of architecture (Galfetti, 2008): a constant pursuit of constructing a space attentive to both the urban realm and the territory itself.