1. Introduction

In the wake of the Second World War, the myth of progress, machine, speed and change permeates modern architecture and its iconic representation, becoming its symbol and invoking a new ideal of progress. It soon became necessary to give a physical (not necessarily material) aspect to what would later become the pivotal point of the IT revolution: the matter of information (Picon, 2010). This defines the paradigm of the “information society”, the post-industrial society characterised by the prevalence over the industry of immaterial goods, information and a large amount of data produced and requested in several disciplinary fields. Architecture, as a situated cultural production and a reflection of the changes in society and in its time, soon approached this silent revolution that in a brief time would colonise many different areas: the IT revolution. From the 1950s onwards, the widespread diffusion of information technology and, above all, the transposition of computational processes into different spheres, characterised the industrial, technological and social development, in an attempt to tackle and resolve the so-called crisis of control (Beniger, 1986), i.e. the need to manage increasingly complex and numerous data.

This change is emblematic of what digital technology has brought about in many areas, namely the shift of the project’s focus from the ‘object’ to the ‘subject’ (Saggio, 2010). Information technology[1] introduces the concept of automation, i.e. the possibility of automatically processing data, according to the rules and principles of computer science and transforming them into information. In this sense, it is fundamental to understand how it has produced an evolution of knowledge from an epistemological point of view: it attributes content to data only through direct correspondence with a system of reading and coding symbols, capable of defining a meaning. Only in this way it can an element of knowledge. Therefore, data can be considered as an architectural subject (as they are translated into information) that constitute an important step in the learning process (Ackoff, 1989). The ‘signifier’ (the data as raw material, without explicit intention), collected through the most modern technologies from the surrounding environment, becomes ‘signified’ and lends itself to the reading and interpretation of the architectural fact (Kitchin, 2014). This means that in this specific historical and cultural moment, architecture is the receiver of a complex system of information that contributes to its change in terms of form-finding and construction. In the same way, architecture, reflecting changes in society, has also absorbed the computer and digital components in its definition and production processes. As architecture has incorporated the digital transition, or the so-called “Second Digital Turn”, by trying to adapt its methodology to an exclusively technology-driven approach, it has shown its aptitude to reflect the cultural values of its time, space and society. What, however, can be noted is that the new tools, that have been introduced to facilitate and empower architecture, have replaced not only the process of creation but also the process of conception, so much so that Mario Carpo believes that architecture has absorbed the results of the digital revolution entirely passively (Carpo, 2017).

2. Shape and Process: Two Different Approaches

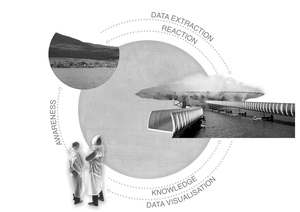

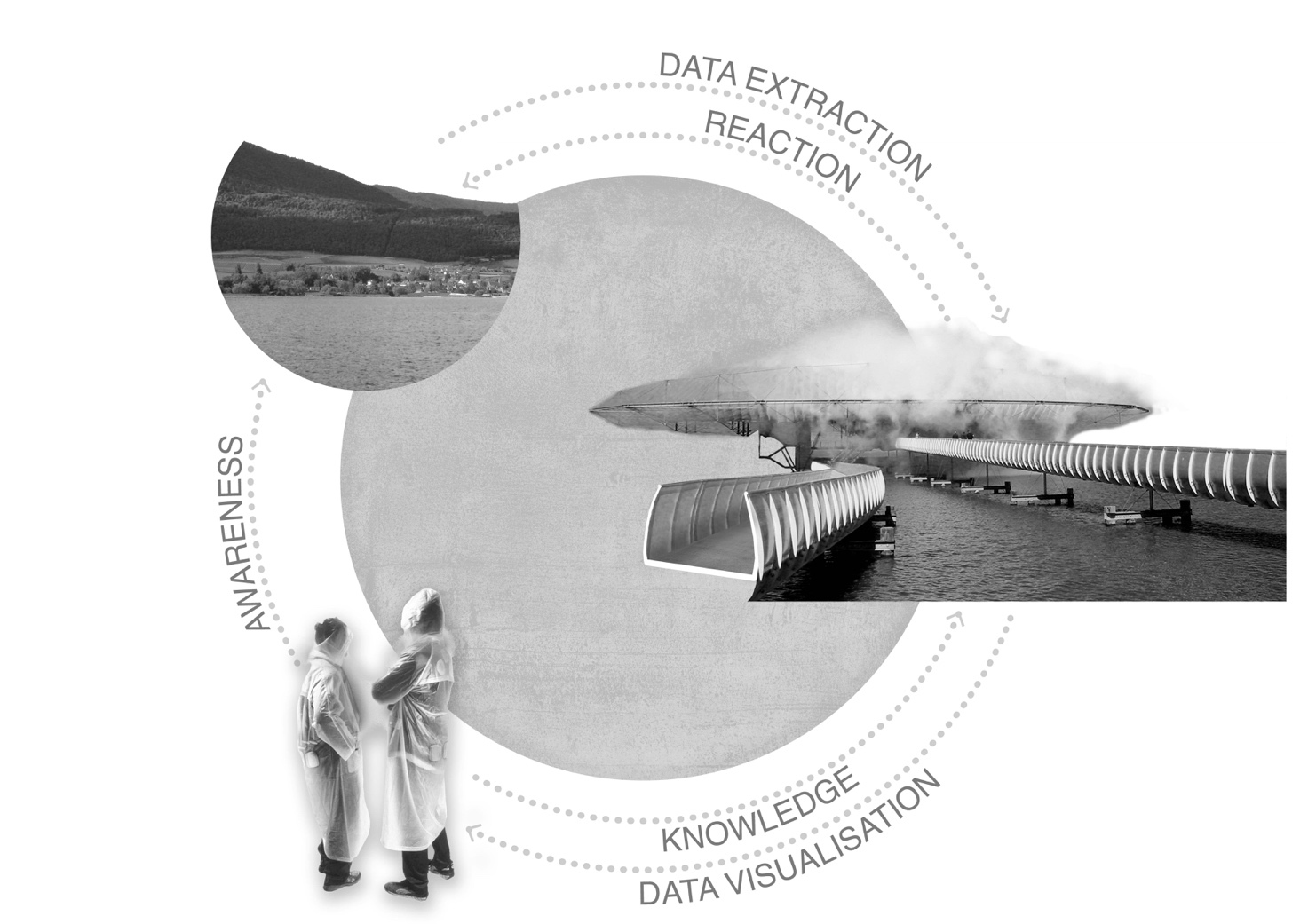

As known from history, at the end of the Twentieth century, society was moving towards an epoch-making innovation, in a cultural moment of social and productive impetus which would intensify its production until modern days. First, the computer revolution and then the digital revolution were greeted in architecture with both great diffidence and exaltation. In contrast with the idea of standardisation, the IT revolution introduced, on the one hand, the concept of complexity of forms, processes and relationships - through the tool of the diagram for example (Van Berkel & Bos, 2002)- and on the other the feature of interactivity. The introduction of interactivity has been a pivotal moment in the definition of new relationships between the building, the user and the environment, in a dual and complex relationship (Fox, 2016). It is possible to identify two different types of interaction: the first one focuses on the spatial transformations introduced by the digital tool’s ability to manage the complexity of shapes[2]; the second one, instead, relates to the design operations that the project can show within the communication with the external factors (Fig.1).

This latter type introduced the ability to define new relationships within the transition from the mass to the individual (and therefore to progressive customisation not only of the needs of the individual but above all of the products). Also, architecture, reversed this way of thinking, quickly highlighting its ability to become interactive. This new feature allows establishing an active dialogue between the building, man and the environment, thus underlining a connection between ethical and aesthetic aspects. This led to two different trends: on the one hand, the central role of information, making explicit its representative and symbolic value; on the other hand, the progressive exaltation of action and performance, as a means of emphasising the pedagogical character of buildings at different scales.

With this premise, this article aims to suggest a parallel reading of two emblematic cases study which, a few years apart, have shown this difference in the approach to architecture and interactivity: the Saltwater pavilion (K. Oosterhuis, 1997, Neeltje Jans) and the Blur building (Diller and Scofidio, 2002, Yverdon-Les-Bains). Both associated with the desire to exploit technological data to design from it (in this sense also providing interesting ideas for data visualisation), these two buildings show a point of rupture with the past, and yet with their current time. Their relevance lies not only in this reason but especially in the context they have been built in. Architecture, on the turning of the century, is rapidly changing: on a hand, in the definition of the form, more fluid and digitally controlled, along with the idea that will be later defined as ‘frozen flow’ (Picon, 2010); on the other, on the relation that the buildings (for different reasons) create with the environment. Certainly, these two buildings are not the first attempt to try to create a relationship with the environment: vernacular architecture has always tried to create an environment-based solution to make the building more efficient. What can instead be considered an interesting exploration in the same period is the IMA (Institut du monde arabe), built-in Paris in 1987 and designed by Jean Nouvel. The complex façade system, which recalls the moucharabieh pattern, was supposed to change (with an open/close movement) concerning the outdoor lightning, so to give the inner space different atmospheres. The reason behind it was mostly related to the intention of creating a connection with the Arab world, rather than establishing a relationship between the environment and the user or, to have a real impact on the environment itself. The difference pointed out ten years later is that through data it is possible to transmit a specific knowledge and also that it is possible to establish a direct interaction between users, building and the environment. The two pavilions presented in this paper, envision the idea that a building can be capable of adapting to the needs of its environment and providing new forms of knowledge by raising awareness of external environmental changes. Therefore, within this framework of the investigation, it is possible to understand that the element of the facade can have (again) a pedagogical character. Furthermore, it also breaks away from the initial interpretation of the façade as a ‘screen’ and becomes something other than itself. Although with different purposes and timeframes, the Saltwater pavilion and the Blur building are two buildings with the same functional programme, i.e. they are two collective cultural buildings, which show investment in the latest technologies for digital design processes.

3. Saltwater Pavilion: a Sensorial Journey into the Intangible

The digitalization of architecture has inevitably brought to a moment of transition that emphasized several changes. At first, the way the project is represented was changed -at first in two-dimensional form, then three-dimensional and finally today through complex information management systems- but also how the project itself is conceived (Nicolin, 2006). Although great attention was first paid to the morphological aspect of the building, through the distortion of forms and then the modelling of the envelopes, at the end of the Nineties new technologies allowed to assimilate the characteristics of computer systems within buildings. This introduced the possibility of putting on the scene –metaphorically or purposely- a correspondence between information through the architectural elements themselves, introducing what the Dutch architect Kas Oosterhuis would later call the Hyperbody (Oosterhuis, 2003). The building thus begins to be understood as a dynamic, interconnected and mutable object, in line with the development of computer systems and the first websites[3].

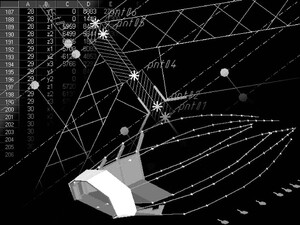

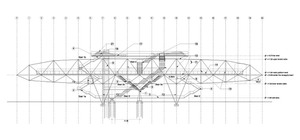

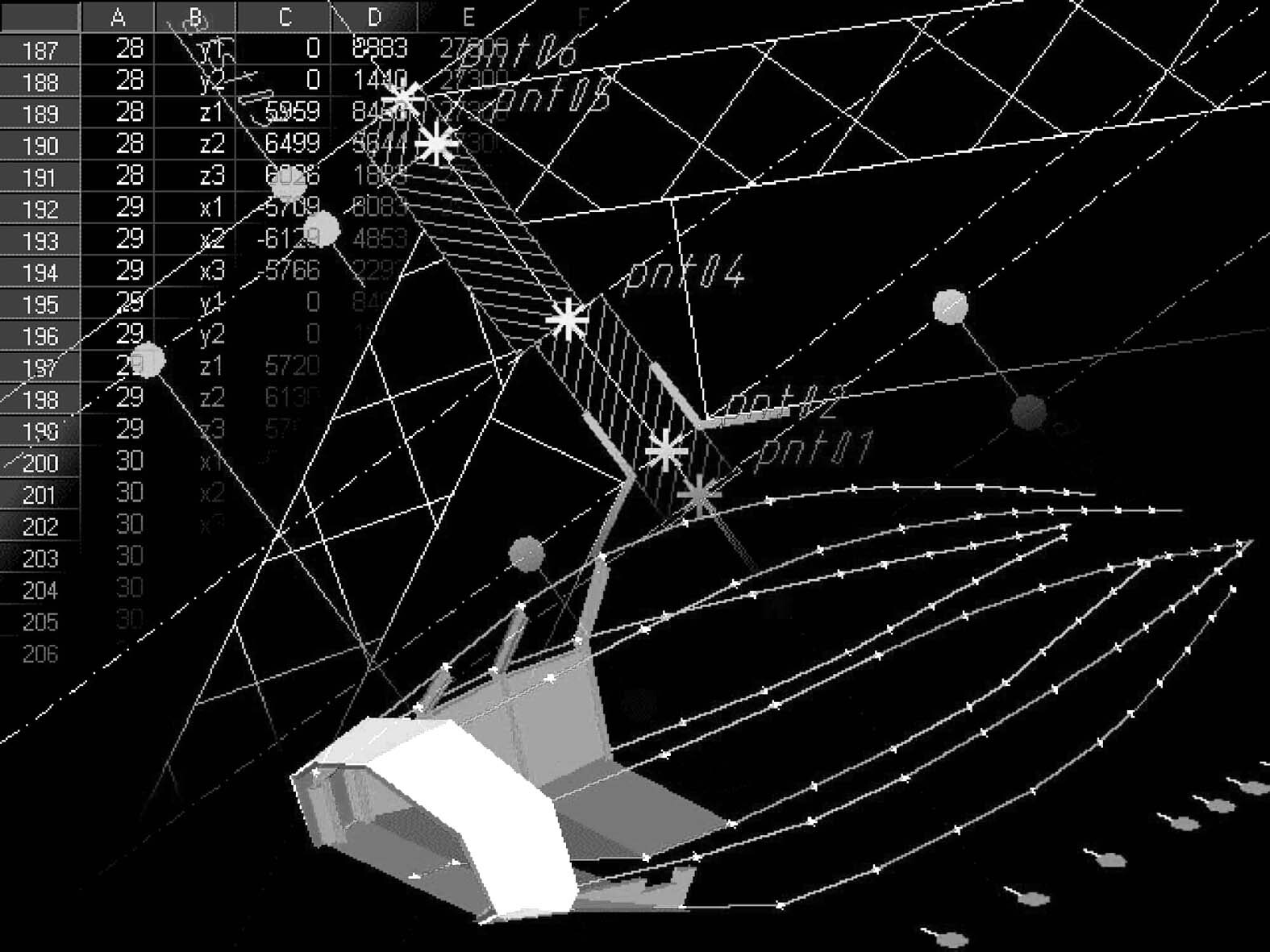

In the Saltwater Pavilion, built-in 1997 in Neeltje Jans in physical continuity with the Freshwater Pavilion by NOX studio (built as well in 1997), the entire design process is centred on the elaboration of flow diagrams which define the relationships between the parts (along a process that is certainly not new to a certain kind of architects[4]): it allows the whole envelope and the structure to be conceived entirely on digital software, through the relationship between points on control lines and management software (Fig.2). The input sensors, the interfaces, and outputs -that control the behavioural system of the building- are firmly introduced (Oosterhuis & Engeli, 2002) and constitute the relevant main elements of the building. Identified as the first «concrete fiction» (Oosterhuis & Engeli, 2002, p. 17) of the ONL study and conceived as a Hydra that follows the visitor in the form of a structural element, the building is directly linked to a weather station positioned on a buoy in the North Sea. This connection with a data collection infrastructure transmits the gathered information to a computer which processes and subsequent transmits it to the actuators in the building. This connection marks the difference with the contemporary building that engages the relation with the environment, thanks to its dynamic process.

Based on the information received, the building adapts in real-time its light and sound effects on the inside of the building, through the use of fibre optic lights and diffusion elements. At the same time, with a sensor board, the visitors can interact with the indoor space using devices that affect lighting and sound (Oosterhuis & Biloria, 2008). A result is a place always manifested in different ways, which is constantly based, on the one hand on the behaviour of the visitors, and on the other hand on changing external weather conditions (Fig. 3). The singular behaviour allowed by the new technological components introduces the swarm paradigm: the building is conceived as a set of different and autonomous elements (each of them has its shape, position, colour and code) which are inextricably connected to work simultaneously. The biological metaphor is predominant in the production of Oosterhuis, who identifies the genetic code as the generating element of the project itself[5]. The interest for the biologic element is not intended as an organic metaphor (as the middle-Nineties production would have suggested): on the contrary, the Dutch architect meant it as a way to extract from nature a ‘living’ pattern so to create a computational system able to execute complex interaction in real-time (Oosterhuis, 2011).

In this sense, he transposes the natural behaviour into the design process, justifying and enabling several adaptive transformations (Fig. 4). The building itself is a sensor-adaptive system as it is conceived as a living body, capable of changing form and content in real-time. Furthermore, at the same time, it is itself part of a network in which data is continuously shared and information is continuously produced. This characteristic defines the building as a flexible networked information processor within a continuous self-learning environment. This capacity, together with flexibility, marks the difference between reactive and interactive, the latter being understood as a circular ‘demand-response-demand’ system (Elmokadem et al., 2018), whether analogue (deliberate control), automatic (reflexive control) or hybrid (Kolarevic, 2009; Sterk, 2005). The idea of a circular system, therefore, is easily linked to the possibility of having a structure built in a continuous state of the computation, adapting its structure and envelopes, its colours and patterns: a Hyperbody that changes in real-time.

4. Blur Building: Making the Tangible Invisible

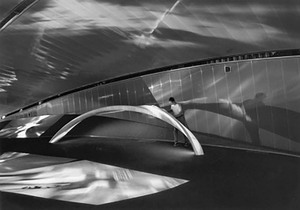

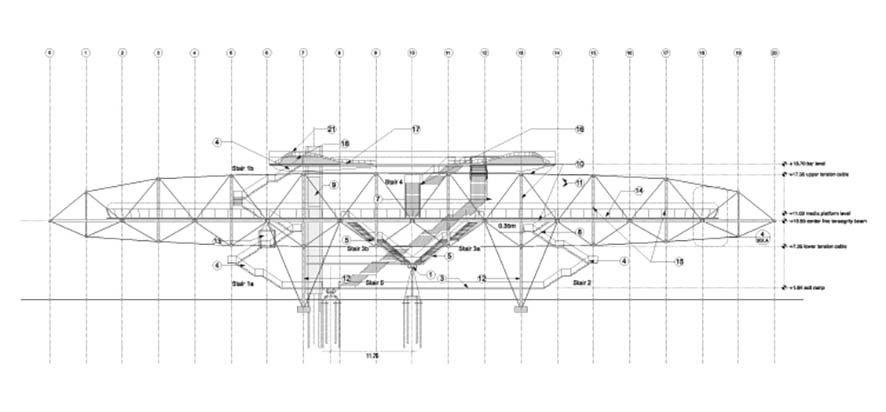

Similarly, in the Swiss pavilion designed and built-in Yverdon-Les-Bains by Diller and Scofidio for Expo.02 in 2002, the interaction between the user, the building and its surroundings is put on the scene on the borderline between art and architecture. Many reminiscences of Buckminster Fuller’s projects of large structures enveloping a space are transposed in the Blur building, defining an enormous tensegrity machine, a ninety-meter oval loaded on bipyramidal supports and steel pillars (Fig. 5). This slender structure, compared to the large proportions of the pavilion, stands fifteen metres above the water level of Lake Neuchatel, to which it is connected by a footbridge.

The building is based on a very high level of technological complexity, concealed behind the simplicity of the materials used: a network of sensors on the outside of the building detect the humidity, temperature and wind and transmit this information to the actuators inside the building. The information processed activates the mechanisms of the numerous nozzles on the surface of the building, which spray water mist from the lake at different intensities depending on the data collected. The artistic intervention puts in place two types of interactions (at two different scales): in both of them, the building plays a crucial role. The first establishes an inter-relationship between the building and the environment, whilst, on a smaller scale, the second one relates the building and the visitor, through the sensors on the ‘brain coat’[6]. In this way, the Blur building stages a new relationship between architecture and the digital world in an overtly spectacular way, suggesting a change of perspective around the central theme of ‘looking’. If visitors expect to see something once they arrive at the pavilion, what they will see is nothing, “spectacularly (about) nothing” (Marotta, 2005).

The result is that the façade of the building cannot be a subject of interpretation, it is never identifiable, its shape is in constant movement and the transformation is unpredictable. The visitor passes through an ever-changing environment, perceives an iridescent panorama and can relate the variation of the natural phenomena around him from the intensity of the steam emitted. In a more accentuated sense, Blur is itself information: the collected element defines the character of the building and prompts a formal transformation. In this sense, the traditional antinomies of inside-outside, open-closed and near-far are broken down. However, this pavilion shows a way of linking the ‘material’ and the ‘immaterial’, the ‘physical’ and the ‘virtual’, giving a changing aspect to external variations in real-time through data.

5. Conclusions

Both examples show an embryonic approach to interactivity, suggesting that with technological advancement, those elements that at the beginning of the year 2000 introduced the possibility of multiple reactions (related to the lighting system, sounds, and smells) could later constitute a more complex architectural project. Architecture is also a matter of prefiguration within the toll of the imaginary.

With a multidirectional and non-recursive idea of time, the architectural project can nowadays be conceived as a process open to non-(de)finite scenarios, as well as to different configurations and interactions between all its parts. Therefore, introducing interactivity meant, on the one hand, to crystallise a paradigm shift in the design process, putting the subject before the object, personalisation before standardisation and variability before seriality; on the other, it implied –and still does- a radical change in the core idea of time, which allows for continuous spatial configurations based on the interconnected properties of the parts of an overall complex system. The search for the interaction between building, exterior and also user, provides nowadays a new tool of knowledge that the project itself controls and manages. In other words, these buildings state the difference with the past (and with the already mentioned IMA) because of the presence of the digital element which allows data not just to be captured and stored but, especially manipulated. They can thus be considered as complex computer machines which can put in place (or put on the scene, according to their performative character) a spatial manipulation of digital data. In this definition, it is then possible to recall Manovich’s definition of 'new media, especially for their programmable nature, that allows them to be altered through a computer (Manovich, 2002).

In conclusion, in these cases study, the two buildings are both producers and a store of data: the mixture of the physical and immaterial aspects of architecture is mediated by IT and digital procedures, allowing information to be considered as a real constitutive material of the architectural project. It is not then just a matter of (virtual) connections: the change induced by the information collected does have a spatial impact on the building itself. The visitors of the pavilion would not be able to experience the same kind of space twice because the external conditions would never be the same: this means that this kind of architecture also implied a certain level of unpredictability. In the same way, the active interaction between the building and the users would stimulate an always-new response or a change of habits in the users, whose awareness about environmental issues would be indirectly raised. In this sense, it is a scope of the author to underline the importance of the cases study non only for understanding the innovation that they brought to the architecture and technology field, but mainly for the inner purpose of using the architectural elements (such as the façade) and some specific characters (such as the multi-temporality or the multi-scalarity of the building) to create a bond between the building, the user and the environment. In a historical moment in which architecture was not yet merged with mass media communication, ONL Diller and Scofidio implicitly attribute the facades to the pedagogic role of architecture. The meaning extracted by the collected data is clearly shown on the façade (even when it does not appear) through a specific and unique code. At the basis of the responsive and adaptive architecture that in more contemporary times has been designed, and that evolves from these embryonic interactions, there is still the idea of relating the (in)tangible and the (in)visible. The information considered as a real constitutive material of the architectural project defines the set of relationships that the building establishes with its surrounding environment.

Related to this revolution, it is important to remember also the definition of the “information society”, the post-industrial society characterised by the prevalence on industry of an intangible asset, information (a large amount of data produced and required by research from different disciplinary fields).

Numerous currents have followed the development of the IT revolution in architecture, especially with regard to form. Among these, Greg Lynn’s thought on the fold as the main means to manage the digital project, starting from a re-reading of Gilles Deleuze’s book The Fold: Leibniz and the Baroque it is remarkable. The complexity managed through processes of visualisation and numerical management of information appears to be the central theme of the introduction of the digital elements in architecture, which has triggered profound reflections on the concept of a new aesthetic. In this way, it stages and prefigures relationships of a topological or parametric type, capable of constituting a genetic code which is both a generator and a regulator of the project.

It is no coincidence that liquid spaces or declared biomorphic systems, as Marcos Novak describes in Liquid Architecture in Cyberspace, are a main matter of interest: «[…] Liquid cyberspace, liquid architecture, liquid cities. Liquid architecture is something more than kinetic architecture and robotic architecture, an architecture of fixed parts and variable links. Liquid architecture is a breathing, pulsating architecture. […]Liquid architecture produces liquid cities, cities that change when a value changes, where visitors with different backgrounds see different landscapes, where surroundings change with shared ideas, and develop as ideas mature or dissolve.» (Novak, 1993).

This element is central to the debate of the end of the century, especially in terms of the new aesthetics that derived from it: furthermore, it introduced into the representation new elements proper to computer science, thus adapted to better explain architectural complexity. Computer systems work through simple relationship between complex elements, usually represented by flowcharts, which are graphic representations of the operations to carry out in order to execute an algorithm. These graphical elaborations, suddenly applied in the architectural field, make explicit the need to establish hierarchical and causal relationships between different elements that constitute the building, not only at a technological level, but above all at a spatial level. A first clear example is represented by the diagrams drawn up by Cedric Price to determine a dual relationship between the actions of the building and the user. The building is thus configured as a place of constantly evolving practices, a physical and spatial construction of that continuous movement that the avant-gardes of the early 20th century had already studied and represented through new languages. (Andaloro, 2021)

«The essence is in the genetic code. The genetic code of a building body is a set of rules and algorithms, animated by the circumstantial parametric values placed into the formula’s making up the genetic code. The visual appearance is the outcome of the process running the genetic script in a site-specific and time-specific environment.» (Oosterhuis, 2003, p. 38-39).

The project of the ‘braincoat’ by the same architects should have allowed people to express their characters through the use of a smart raincoat provided at the entrance of the building. In order to furnish visitors an alternative way to see in the fog and meet other people, Diller and Scofidio developed the idea of using lights for people to communicate to each other. Based on a form that visitors filled in at the entrance, each braincoat was able to create a personal profile the would be able to create an involuntary reaction when approached to another ‘braincoat’, based on the information received. A panel on the chest would show the affinity or antipathy with a range of colours from warm red to blue-green.