1. Introduction

Throughout the history of architectural criticism, there have been several ways to define how a building could establish meaningful relationships within its larger spatial/cultural context and, thus, define a scale of values through which that work can be analyzed/appraised. The majority of them imply an understanding of the formal aspect of a specific piece of architecture that takes into account specific and contextual cultural elements; whether we refer to a broader framework rooted in the use of narrative, allegory, figures of speech - ex. the metaphor -, the whole investigation revolves around the aesthetical values of that architecture and how those can transfer a functional program to its design. More interdisciplinary analyzes of this question orbit around the importance of considering signification and representation (Peirce, 1985) and are influenced by the fields of semiology and elements such as signs, syntax, and iconography in architecture.

Nevertheless, despite the interest that might arise around these specific methods of inquiry in the architectural debate, all of them are grounded in a bias that the spatial discourse regarding architecture intends architecture as-object leaving less importance to the experiential moment generated by its existence and impoverishing the intimate relationship that occurs among time, space and the body of a subject.

Although its indisputable importance in our existence as human beings and its being a primary category through which we mark our presence in the flow of history, when it comes to architecture Time has always been considered a subsidiary means that might – or more often might not – be taken into account concerning its capacity to lead and critically analyze design processes and their outcomes (Judson, 2011). If in the discourse around architecture too much emphasis has been placed on its purely spatial aspects, this is due also to our modernist notion of space as part of a physical/measurable, thus, objective knowledge, and the ease of its representation through established and traditional techniques. Such a narrow perspective on the development of an exhaustive discourse on architecture was already highlighted by Sigfried Gideon. In its Space, Time and Architecture, he affirms: Exhaustive description of an area from one point of reference is, accordingly, impossible; […] In order to grasp the true nature of space the observer must project himself through it. (Giedion, 1941), underlining that even though space and time exist as well-defined reference points and categories in language and common thought, rarely they are present together when at stake there is the interpretation of our lived experience with the second one somehow subservient to the simpler and more obvious spatial referents of human existence. The aim of this paper is to disclose the possibilities disclosed from by incorporating and interpolating the notion of temporality into architecture throughout the understanding of the reciprocal relationship existing between body and space and some spatialized representations/projections of it. Using art – and the work of art – as a critical lens through which it is possible to explore differently the relationship between time, architecture, and space, the main goal is to demonstrate how architecture can be intended furtherly not as an ‘isolated event’ but as a part of a temporal continuum able to activate multiple and overlapping temporalities in our present. To do so, the methodology used grasps in a comparative study between different works of art and architecture, and the common relationships they create in the public space they are inserted in, in order to highlight the interdependency among the two fields under the concept of time and temporality.

2. Which Time? Some clarifications on the authors’ positioning

What is the time? “If no one asks me, I know, if I want to explain it to anyone who asks me, I don’t know anymore” (Sant’Agostino, 2006).

Following this famous quote from the theologian and philosopher Sant’Agostino, it seems that giving an unambiguous and satisfactory definition of time is complicated, and over the centuries, it has been a matter of reflection and study by all philosophers, thinkers and scientists. Aristotle tries to provide an explanation linking time to space by sensing its descriptive properties of the movement of objects in space:

“Time is the number of the movement according to the before and after”. (Taroni, 2012)

In the notion of movement, the before and then indicate any type of progression and are distinguished by numbers. This leads us to think that in our perception of reality, time could be visualized through movement; objects through their movement from one point in space to another, thus changing their geometrical position, contribute to the idea of the flowing of time. Indeed, according to Aristotle, time is therefore the expression of a movement and is inextricably linked to the concept of space. During the eighteenth century, Immanuel Kant defines time and space as two a priori categories without which there can be no perception of reality

“Time is not an empirical concept, derived from an experience: since simultaneity or succession would not even fall into perception, if there were not a priori, at its basis the representation of time. Only if we assume time is it possible to represent that something is at the same time (simultaneously), or at different times (successively)”. (Kant, 1985)

The consequence of this philosophical thought is the conceptual and practical impossibility of interacting with these two categories, since by definition they are placed outside our actions, a priori, that is, as an essential starting point for any human action. This concept carries with it the idea that time can be a perfect, abstract and incorruptible category, far from the transience and accidentally of human perception, and directly linked to the notion of infinity.

In the twentieth century, Albert Einstein and Henri Bergson developed their theories, the former in the field of science, and the latter in philosophy. Einstein, in 1916, published the Theory of General Reality which redesigns our idea of space and the universe, introducing a concept of relative time and space, that is, not absolute and inextricably linked to each other, because one is a consequence of the other. According to that, the concept of time presupposes that of simultaneity; that there is no such a thing as an absolute, a priori time that flows independently of the things in the universe. Time is always relative to the observer’s reference point; there are different times relative to the moving observers who measure it.

At the same time, Henri Bergson published his theory of time as duration. According to the French philosopher, spatialized time serves only as a mathematical convention without any phenomenal value.

“When I follow with my eyes on the face of a clock the movement of the hand that corresponds to the oscillations of the pendulum, I do not measure the duration, as it might seem; Instead, I limit myself to counting simultaneities, which is very different. Outside of me, in space, there is a single position of the hand and the pendulum, as nothing remains of the past positions. Inside me, a process of organization or mutual interpenetration of the facts of conscience takes place, which constitutes the true duration”. (Bergson, 2000)

For the French philosopher, therefore, time is not a “thing” but a “progress” a continuous flow of our consciousness that continually becomes present memory, which continually re-elaborates our past experiences by updating them and our actions in the present are our attitudes with respect to the future. Duration is therefore an interior space, an intimate experience of phenomenal reality; space is excluded, and becomes exteriority without succession.

«Bergson does not explicitly pose the problem of an ontological origin of space, it is rather a case of dividing the composite in two directions, only one of which (duration) is pure, the other (space) is the impurity that denatures it». (Deleuze, 1991)

This division leads us to perceive time and space as two elements in some way indissolubly interconnected even if one (time) can be perceived as an internal notion and give us the consistency of the perception of the other (space) which is ‘impure’, that is, conditioned by the accidents of the life that takes place inside and around it. Our positioning on the idea of time and space also moves from these concepts. Time is inextricably linked to space, therefore the field of action is consequently closely linked to the “I”, to the perception and narration of the human being, of human existence. And it is linked to Space to the extent that today – even following the discoveries of quantum physics – we can no longer treat these two concepts separately, scientists always refer to space-time, treating space the same way as we are treating time, as a flow. This brings us back to Aristotle’s thought of time linked to space:

“Space and time also belong to this class of quantities. Time, past, present, and future, form a continuous whole. Space, likewise, is a continuous quantity: for the parts of a solid occupy a certain space, and these have a common boundary; it follows that the parts of space also, which are occupied by the parts of the solid, have the same common boundary as the part of the solid. Thus, not only time, but space also, it is a continuous quantity, for its parts have a common boundary” (Aristotele, 1970)

Aristotle refers to solids and voids and the relations of forces between an object and the environment that surrounds it, but he also considers time and space as a single flow. If we keep the past, present and future conceptually separate, time as a flowing movement is unreal, because only the present, understood as a continuous flow, is real.

This leads us to consider temporality (and spatiality) as part of a single flow, which, as Bergson intended, forms duration, which thus creates a ‘thickness’ that becomes our field of action.

After disclosing the notion(s) of time followed in the construction of the essay, and from whom the applied methodology starts, some needed concepts regarding the incidence of time in architectural design and theory will be presented and discussed in the further section to understand the specific reference in a closer relationship regarding time, temporalities, and architecture

3. Some brief notes on Time and Architecture

Browsing the history of architecture to try to understand when our current object-oriented conception of architecture emerged, we will be surprised to discover how, in ancient times, there was a more intrinsic and pronounced relationship between the latter. According to Bishop (1982), there is a dormant interest in architects and planners to encode into their works temporal messages: an interest that comes from ancient times. Greek architecture was a majestic example of architecture intended as ‘mnemonic devices’ where highly imageable places were used to let people wander through a memory environment permeated by time transcending the here and now. Inspired by the Ellenic tradition, Roman architecture took it one step further with an accentuated passion for fluidity and the continuity of space that overcame Greek’s staticity making every Roman able to actively participate in history and confirming the of time as a basic dimension of human existence embodied and enforced through the spatial characteristics of architecture. In regards to Roman architecture, the Danish author and architectural theorist Norbelg-Schulz stated that "the Romans have effectively concretised the dimension of time:

Roman articulation represents an answer to the problem of how to give space continuity and rhythm, that is, dynamic order. Space becomes the varied and dynamic, but ordered, stage where history takes place. (Norberg-Schulz, 1975, p. 112)

Such an idea of ‘mnemonic devices’ has permeated for several centuries the development of urban environments. As confirmed by Lewis Mumford, despite the emergence of large and more spread cities, their architects and urban planners did their best to integrate man’s sense of past, present and future (Friedmann, 1962). In his writing, he affirms that the sense of the city as a tool for memory conservation and storage is one of its most important and peculiar and invaluable functions.

However, the development of modern philosophy based on a rationalistic conception of knowledge inspired by the precision and certainty of the mathematical sciences in every aspect of knowledge completely oriented this discussion towards other principles. In The Production of Space, Henri Lefebvre and Donald Nicholson-Smith pointed out how René Descartes became a fundamental reference point for the common understanding of space and that “with the advent of Cartesian logic… space had entered the realm of the absolute. As Object opposed to Subject, as res extensa opposed to, and present to, res cogitans, space came to dominate, by containing them, all senses and all bodies”. What is fundamental to understand is that Descartes’ idea of space refers only to its measurable extension in these three dimensions. Indeed, he argues that length, breadth and thickness, are the essence of corporeal substance, and thus, space, it is clear the latter becomes a mere physical property of matter: an abstract concept that can be measured, divided, shaped, and moved (Till, 2009, p. 120) and serves to us just to consider the amount of space that an object occupies and - or the distance between a series of them - most probably does not correspond to our experiential comprehension of it.

This abstract space stands as something external which can be experienced from a passive distance precisely because it is external to the subject and represents an oppressive act (Till, 2009, p. 123) since it is rooted in all those characteristics of architecture where time is absent and that is easy to commodify and control from the power. If space undergoes this fate, time too, so linked to it in antiquity, undergoes its linearization and progressive simplification. Time is then expelled from the architectural object and the experiential moment of the subject itself, causing a predominance of the visualization and impoverishment of the urban environment which is considered only throughout its characteristic of conveying visual meaning.

Even if Modern Architecture, and much of our contemporary architecture resulting from that, has inherited some of its founding principles precisely in this strongly aestheticized vision of space and architectural form throughout the annihilation of a temporal component, what we argue for it’s the comeback of a sensibility where architecture can be analyzed not anymore as a singular, isolated, and autonomous realm, but throughout its engagement with everyday dynamics and the real world. Recalling the notion of space as subjective geography, we position ourselves on the idea of space as a social product in which different spatial practices where the experiential time of its inhabitants - made of coexistence and simultaneity - activates dynamics of ‘spatial rewrites’ that alterate commodified idea of the space as a mere problem of visualization. We aim to reintroduce the importance of the idea of time in architecture through the point of view of its main actors, passers-by in urban space, and focus our attention on heterogeneous experiences that are not grounded on a predominant central point of reference or architecture as an exception within the flowing of time.

Among the different social practices (politics, activism, performance, etc.) that can be used for this objective, we decided to focus on the realm of art and see how, through its insertion close to the architecture, it could participate in this deeper understanding of the inner structuring of space itself, especially if we intend time as a succession of states. In order to do that, the exploration will revolve around the word ‘contingency’ - a future event or circumstance which is possible but cannot be predicted with certainty – as a means to question the normative interpretation of space.

4. Contingency in architecture/time/public space as an operative category of time

Vitruvio wrote: «Architecture depends on ordinatio, the proper relation of parts of a work taken separately and the provision of proportions for overall symmetry». (Till, 2009)

This definition analyzes the architectural object as something that must respond only and exclusively to itself, inserting the idea of order, as a purifying factor of the architectural object. Susan Sontag reminds us how: «Order is the oldest concern of political philosophy, and if it is plausible to compare the polis to an organism, then it is plausible to compare civil disorder with an illness». (Sontag, 1979)

If we move this metaphor to architecture, we will see how the idea of order, rationality and self-satisfaction are the basis of the idea of architecture as a permanent element, detached from time, tending to infinity. The trend toward order, towards geometric perfection and the cleanliness of the elements, manifests itself as the extreme attempt to detach architecture from the passage of time and from the events of everyday life that flow parallel inside and outside the building.

In reality, an order can only exist as a set of rules that abstractly govern the notions of design, engineering, materials, and administration; everything modernism strives to regulate in the spasmodic search for truth, that could be found in the absoluteness of geometric form and pure colours. However, the truth derives from reason, that arises from the analysis of phenomenal reality, and it is always in the phenomenal reality that architecture has to deal with, not in pure abstraction, but the impurity of everyday life, of the unpredictable actions and reactions of the users of the building.

This apparent dichotomy hides an essential relationship, between order and chaos, which is at the basis of the existence and perception of the human world. That’s why the idea of chaos, of what we cannot rationally order and control, the notion of chance, of contingency, cannot be accepted by modern architecture, because it risks making the geometric and perfect origin of the architectural project imperfect.

«The quest for eternity is thus both intellectually problematic and actually doomed to failure» (Till, 2009).

It is not a question here of preferring one notion to another, order over chaos, or vice versa; rather, it is a question of understanding how indissoluble and dependent one is on the other and understanding that what we cannot control, what goes beyond the possibility of being calculated a priori, is not necessarily a negative element, but a possibility, as Hegel also defines it, the «unity of actuality and possibility» (Till, 2009). This possibility is what architecture has had to deal with, especially when the postmodern has highlighted the broken dreams of modernism, «The history of human being, for its part, is going to remain contingent, agitated by sound and fury» (Latour, 1993). Tracing a new idea of temporality «There are no longer – there has never been – anything but elements that elude the system, objects whose date and duration are uncertain» (Latour, 1993) through which the whole idea of perception of reality has changed. Shattering into infinite, incalculable, overlapping and interchangeable levels, creating a thick and continuous flow of time within which we move, a rhizomatic time that allows us to live a continuous present, nourished at the same time from our past and our future visions to draw upon at the same time in our now. This vision constantly questions the boundaries of our own being, of our knowledge, of our continually putting ourselves into play, making reality an uninterrupted flow of approaches and visions, an archive without predominant directions from which architecture cannot be detached, in the words of Karatani «architecture is an event, it is always contingent». (Karatami, 1995).

If, as we have seen, architecture is an event in itself, the category of time is the one that most characterizes it, also transforming physical space into a temporal category. «While architects may dream of their buildings coming into the world as fully-fledged durable items with enduring value, the reality is that they always enter the social realm as transient objects». (Till, 2009)

We can try to understand how this being an event that takes place in the thick flow of time of which we are all part, makes it participate in all the events that take place inside and outside of it, as a whole, whose boundaries are blurred and in continuous renegotiation.

In the new concept of our reality: «Nowadays, due to the changes in our global understanding… architecture is no longer considered as the act of creating an artefact that stands alone, tangible, perceived or presented to the senses. From the constraints imposed by this new mental framework, strong, new concepts emerge». (Voyatzaki, 2016)

From this point of view, the architectural object is not only the recipient of the functions for which it was designed; it is not just part of a changing landscape in which it becomes a visual and perceptive element. The architectural object also becomes a place whose construction characteristics, its full and empty spaces, its internal paths and its façade, are keywords of a list that becomes part of a vocabulary of possible interactions with the building itself, transforming it into an open object. If we could translate some notions of sociology into architecture, we could welcome the idea that «The presence of the ‘Other’ prevents me from being totally myself» (Laclau & Mouffe, 1985) thus becoming witnesses of a constant displacement of identity that constantly questions the idea of architectural space (and time).

The intervention of art on the architectural object opens up the possibility that “the other” becomes visible, shifting the physical boundaries and the image of the building into a continually renegotiated elsewhere. Even the work of art, as well as architecture, is a product of the intellect, which takes the form of an object, but which, unlike the artisanal or industrial object, also contains another value, that of making visible the other. The work of art is, therefore, part of the real world, but its appearance, its structure serves to make the other, the symbol, visible. Over the centuries, the idea of what we consider and call a “work of art” has also changed as a result of the influence of new technological discoveries and the social battles that have influenced artistic practices and expanded the possibilities of expression for artists. Along with the possible forms of the work of art, the artists have also questioned the idea of the place where to install and exhibit the work. This has led over the centuries to a reinterpretation of the spatial relationship between work and exhibition space, leading artists to measure themselves with ever-changing spaces with which to establish increasingly interconnected and complex relationships, that overcoming of the imposed order of modernism, in a path parallel to that of architecture. The artists began to see the space in which to exhibit their works, no longer as a white and neutral place, a place that “sanctified” the artistic object by disappearing all around it, without interfering. Rather as a place that had its own “weight” in the structure and perception of the work of art; the work was no longer just exhibited in a space, but installed inside the space, becoming part of it. The idea of exhibition space is thus transformed into the notion of “site” a well-defined place that with its physical, temporal and formal characteristics influences and is in turn influenced by the artistic intervention, because in Foucault’s words:

«We do not live inside a void that could be coloured with diverse shades of light, we live inside a set of relations that delineates sites which are irreducible to one another and absolutely not superimposable on one another». (Foucault, 2006)

Again the idea that the concept of space is part of a flow, part of an event and therefore of a temporal category, and can no longer be reduced to a singularity, to a single thought that takes place according to a linear and a priori defined temporality. In the same way, space cannot be superimposed on the space derived from its encounter with the events that take place in and around it. What we observe is the birth of another space–an event that is born and develops in the contingency of its encounter, art and architecture in the case we are examining, in which the contingency is revealed in the epiphany, in the revelation of the essence of things. What we are claiming is that both architecture and art have gone through the attempt to remove them from the flow of time, in the unsuccessful attempt to make them infinite, but of a fictitious infinity, precisely because it is blocked in a moment that repeats itself indefinitely, remaining for this reason stuck within itself. We have seen how both are in reality an indissoluble part of the temporal flow, and that their superimposition, as a consequence of the breaking down between the rigid boundaries of the categories of architecture, and art, gives rise to a whole new relationship, which confronts us as spectators to something unexpected and that makes us an active part of this relationship, part of this space–event.

5. The space-event through the work of art and architecture. Three keywords for a time-based relationship

This third space–event, therefore, arises as a result of a physical relationship between the space–event of the architectural object and the space–event of the work of art; its interpretation depends on the type of physical relationship established between the architectural object and the work of art. Below we will illustrate three ways of understanding this physical relationship[1] that describe a list born from the vocabulary of the architect’s profession, which no longer implies a singular relationship of the building with its own physical characteristics, but rather an extended relationship between the building and another element (the work of art).

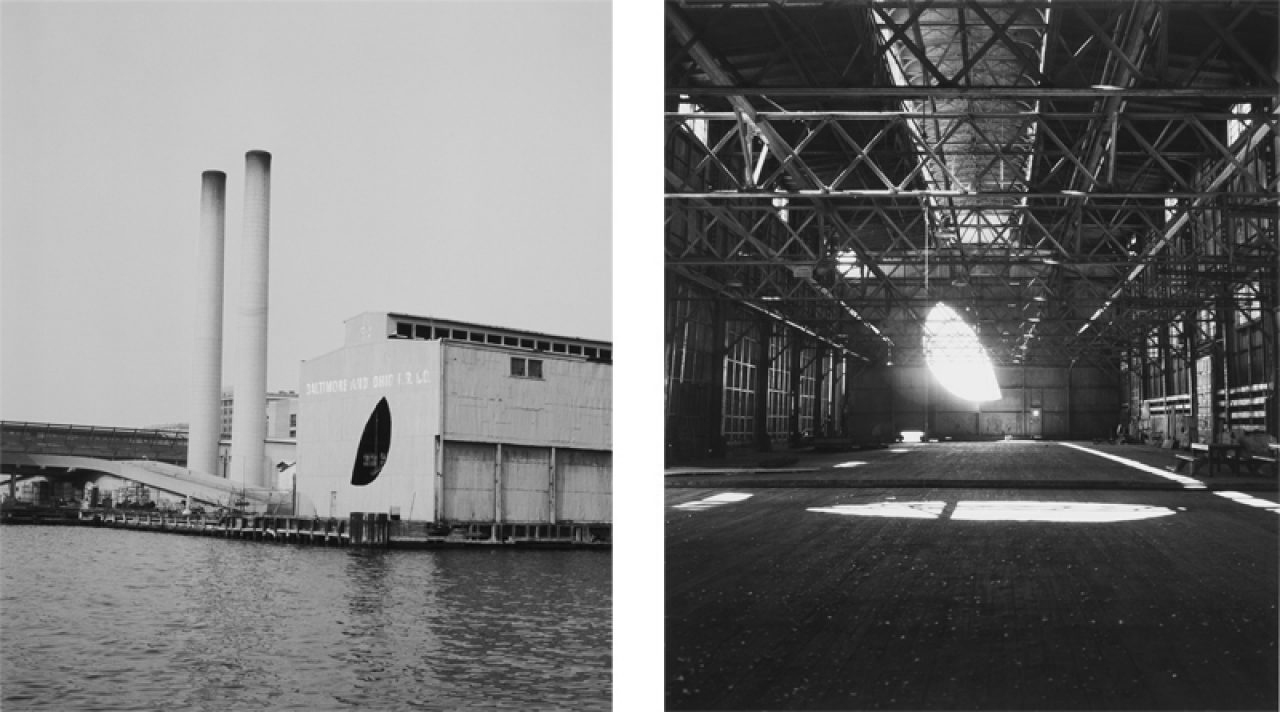

The first word we will investigate is Rewrite. In architecture, this concept is related not only to certain aspects of formal or typological correspondence, but rather in something deeper; something related to the generative principles that underlie the nature of the formal characteristics of architecture (Rogers & Molinari, 1958). Meanwhile, to analyze is significate in the construction of a third-space event, we will analyze Gordon Matta-Clark, Day’s End, created inside Pier 52. The abandoned piers along the Hudson River in New York, in 1975. The building is a quay of industrial origin, no longer in use at the time of the artistic intervention (and destined to be demolished a few months later). The space was formed by a single structure, without internal divisions on the ground floor, 182 meters long and 20 meters wide with a skylight at a height of about 15 meters. A building that the artist defined as a cathedral, and the two industrial chimneys at the side of the structure somehow strengthened this visual parallelism. The artist made some cuts on the very structure of the building, according to his artistic operational methodology. Gordon Matta-Clark was a sculptor who worked directly on architecture, creating cuts on the object. We are in 1975 and the formal origin of Matta-Clark’s signs is to be found in minimalism, even if this geometric shape is somehow “adapted” to the shapes of the building where the artist works. In the case of Day’s End, the cut made by Matta-Clark starts from an elliptical shape to become a reference to sail, since we are located along the Hudson River. The artist realized some cuts, one on the floor under the front wall and one right on the front wall. The light that springs from the opening on the front wall looks like a sacred light, the internal space of the building now functions exactly like a nave of a cathedral from the Christian period, and the “faithful” are immediately struck by the sunlight that enters unexpectedly from the wall in front of them. Walking through the space, they reach this cut, also approaching the cut on the floor that puts them in relation with the water immediately under the building.

The viewer is immediately fascinated by the cuts of Matta-Clark, by their unexpected aesthetics, and this is precisely the fundamental point of these operations; to make the architectural space an unexpected space, which can be travelled differently from the original functions conceived by the designer, in the artist’s words: «There is a kind of complexity that comes from taking an otherwise completely normal, conventional albeit anonymous situation and redefining it, retranslating it into overlapping and multiple readings of conditions past and present. Each building generates its own unique situation.» (Crow, 2003) As we said earlier, there is no superimposition of two unique spaces and times, but a rewriting of the space–event of architecture, through the physical action of art on it that redefines its internal times and spaces. This focuses attention on the contingent circumstances and the different temporal dimensions that are by now indissolubly intertwined in the new version of the building, which from a forgotten industrial place – that is, passed out of the time cycle – reenters it in the form of a spiritual building, where the encounter with architecture (and with art) is unexpected and therefore generates a new perception of the building, together with a new physical relationship with it.

The second word that we will investigate is Juxtaposition, a word that – in architectural terms – related to the state or position of being placed close together or side by side, so as to permit comparison or contrast (Cheesman, 1988), and that coulb be investigated in art through the analysis of Tadashi Kawamata’s Nests, carried out in various places in the city of Milan, in 2022. We will examine the intervention carried out inside the Cortile della Magnolia, on the Palazzo di Brera. The Palace is a 17th-century construction, when it was conceived was supposed to house the company of Jesus (a religious institution). We are therefore in full Baroque architecture, where the plasticity of the building begins to redefine the relationship between the interior and exterior of the building itself. Today the building houses several institutions including the Brera art gallery, the Braidense National Library and the academy of fine arts. Kawamata’s intervention is located in one of the internal courtyards of the building, adjacent to the Botanical Garden, a secluded place, not the main facade of the building in its baroque plasticity, but an internal courtyard that has a meditative character with its facades brick interspersed with windows. The artist’s installation is formally presented as a grid of wooden planks intertwined to create the shape of a nest (ideally a bird’s nest). The theme of the nest is recurrent and almost obsessive in the artist’s research since 1998 and nest installations have been created in various buildings, often strongly characteristic of the cities where they were created. The figure of the nest certainly refers to the universal and archaic need to find shelter, it refers to the moment of childhood, both from the point of view of the child who feels protected in a safe place; both from the perspective of the parent who thinks and builds (ideally as an architect), a safe place for his offspring. The material chosen by the artist – wood – and the sense of precariousness given by the intertwining of the wooden planks, give a sense of the transience of the object in relation, in this case, to the solid architectural structure on which it is installed. The physical relationship between architecture and work of art, the juxtaposition, suggests the possibility that the original function of both objects continues to remain separate; the building maintains the functions and practicability of its internal spaces that it already possesses; likewise, the work of art that we can read as an object in and of itself.

Obviously, as already demonstrated above, both objects have their own space–event that must be read and analyzed separately, but their juxtaposition nevertheless gives rise to a new space–event that shifts our perception and our physical relationship with the architectural space, in this case, the empty space of the inner courtyard. Reconfiguring the architectural space of our daily life through the activation of our childhood memory and/or our parental responsibility and inserting it, together with the work of art in the temporal flow of our continuous present, it refers to a vision of fluctuating and transitory reality. Contingency is revealed in the epiphany of the encounter of this juxtaposition, where the artwork and architecture works together as activators of spaces and times different from those of the objects examined individually.

The last word we will investigate is Addition, in the meaning of adding something – coherent or uncoherent under the topic of style and form (Carpenzano, 2015) – to an existing object. The word will be investigated through Alberto Garutti’s Egg, installed inside the Unicredit Tower, in the Piazza di Porta Nuova – Garibaldi in Milan. The tower is part of an urban regeneration project carried out by the Pelli Clarke & Partners studio and is (to date) the tallest skyscraper in Italy (231m). The skyscraper has a sinuous shape with the convex façade entirely glazed and the concave façade modulated by the sunshades, the building ends with a spire that in some way recalls the spire of the Milan Cathedral, a spiral shape entirely covered with LED lights. The concave façade seems to structurally welcome the square in front (Piaza Gae Aulenti) in which the work of Alberto Garutti also stands. The work is installed in the space of the square, literally climbing through the four floors that reach the ground floor from the garages, opening into the square. The work is added to the complex in different levels of interpretation, structurally, perceptually, and emotionally.

From the point of view of the structure, the work consists of 23 chromed brass metal tubes that develop vertically on four levels, from the parking floors to the upper ones. The work adds to the architecture, becoming an organic part of it, intertwining the brass tubes with the glass parapet that overlooks the oval voids of the ventilation shaft of the four floors along which it develops. Perceptually, Garutti’s work adds sinuosity and organicity to the geometry of the architecture, like a living organism that is added to the space of the architectural object. The first two levels of interpretation intersect with the emotional level, the one in our view more complex and true contingent element of the new space–an event created by the encounter between architecture and art. The 23 chromed brass metal pipes connect the various underground floors of the building, not only through their physicality and their vertical development but also – and above all – through sound. They act as audio propagation tubes between the various floors, relating spaces and architectural paths that have no visual relationship between them. In fact, on each floor, on the glass parapet, the tube opens like housing for the ear, the passer-by will be able to approach the ear and hear the sounds coming from the other floors of the building connected by the tube from which he is listening, without knowing to which plane precisely they refer.

«My work for the Porta Nuova Garibaldi project takes shape precisely in the parallel attempt to enter into a relationship on the one hand with the architecture itself, and on the other with the people who will use that space: citizens, passers-by, casual or daily visitors». (Garutti, 2012)

The work thus becomes a sort of sound map of the building’s events, absolutely contingent and impossible to rearrange. Like a venous system that carries life inside architecture, in all its randomness and emotionality. The work also opens up a new physical approach to the building’s spaces, reverberating our private conversations in a single large flow of speeches, which is what a dense sharing space like the city is, after all. A flow of speeches that foresee or follow actions, a space for action, therefore, highly dense and multi-layered, and highly contingent.

6. Conclusion and further discussion

The analysis of these 3 case studies takes us perceptually and physically into this new dimension of the temporality of architecture where could be found some evidences of a possible connection between different disciplines moving from similar and related concepts. A dimension that has to do with a new relationship that the architectural object establishes, first of all with itself and then with other elements with which it enters into a relationship. As clarified from Lefebvre: «The “imaginary.” This word becomes (or better: becomes again) magical. It fills the empty spaces of thought, much like the “unconscious” and “culture.” …After all, since two terms are not sufficient, it becomes necessary to introduce a third term… The third term is the other, with all that this term implies (alterity, the relation between the present/ absent other, alteration-alienation)». (Lefebvre, 1980)

In this specific case, we talked about the relationship between architecture and a work of art. The work of art in the category so-called “art in public space” arises from public art but is a wider category, which differs from the first, for a more complex relationship with the public space and with the architectural object. A relationship that calls into question the very notion of perception of both art and architecture. There is no longer only a spatial relationship of a formal balance between architecture, the space of the city and the work of art, as it could have been understood until the last century, through the works of modern art installed in the spaces of the city. Now the relationship necessarily becomes a relationship of physical and conceptual interdependence, transforming itself into a space–event, which as we have previously emphasized is built around the type of physical relationship established between the architectural object and the work of art to extend to our temporal perception of this new object–relationship.

The 3 keywords used in this paper to describe this physical relationship between a work of art and an architectural object, are not, as mentioned above, the only possible ones, they are some of the many types of physical relationships that can be established between art and architecture. Relationships that outline a parallel list of keywords, which no longer refer only to the architectural vocabulary, but delineate and refer to a shared space where can exist an inner relationship between different time-framed event that can concur to the definition of a new event. Namely, a space–event that puts in an indissoluble relationship (even if not superimposable as explained above), architecture with what is around it, snatching the architectural object from the idea of being an object detached from the surrounding events, that tends to repeat itself over and over again.

In conclusion, the research that moved this essay focused on reaffirming that architecture is an event, a place that is not a simple endless repetition of a static singularity, but a complex set of contingent events of a different nature, which intersect in multiple planes and multiple spatial relationships, creating a temporal continuum. A continuum that makes us perceive the architectural object as a means to activate different temporalities that overlap in our “thick present” (Till, 2009). It is in its being in the relationship that the time of architecture is not a presumption of repetition of its static nature. In the hyper-connected and virtual world, where the concept of meta-reality has become predominant and which provides a space based on the interoperability between different worlds and platforms, the real world cannot think of being based on fields that are sufficient in themselves to affirm their essence. This vision would make reality a too small place, destined to disappear as Baudrillard hypothesized: «Were it not for appearances, the world would be a perfect crime, that is, a crime without a criminal, without a victim and a motive. And the truth would forever have withdrawn from it and its secret would never be revealed, for want of any clues [traces] being left behind». (Baudrillard, 1996) Therefore, only in a profound connection with the other elements that surround it, architecture (and by extension of method, all the elements of our reality) will have the possibility of creating a temporality that is valid for the contemporary world. A temporality that it contains within itself different spaces and different times capable of generating a new space–time, which has a thickness that goes beyond a singularity destined to disappear in an instant.

For the development of further physical relationships between architecture and works of art, please refer to the PhD thesis currently in process by PhD candidate Stefano Romano, entitled: The Time of Intersection, Time dynamics in the shifting perception of the relation between the work of art and the architectural artefact in public space. IDAUP XXXV cycle, University of Ferrara – Polis University, Supervisor PhD Loris Rossi.