"Time conquers all things … all-conquering, all-ruining time …

God help me, I sometimes cannot bear it."

Leon Battista Alberti, De re aedificatoria

1. Introduction

“What then is time? If no one asks me, I know what it is. If I wish to explain it to him who asks, I do not know.” This quote from the philosopher Augustine (397 C.E.) describes our relationship to time better than almost any other. We know intuitively that every moment flows from the future into the past and is thereby briefly captured by our perception: This is the present. However, as soon as we try to verbalize this felt truth, contradictions emerge. Augustine laments:

I know that if nothing passed away, there would be no past time; and if nothing were still coming, there would be no future time; and if there were nothing at all, there would be no present time. But, then, how is it that there are the two times, past and future, when even the past is now no longer and the future is now not yet? (Augustine, 397 C.E.)

Time can truly twist your brain. In architecture, time often plays a subordinate role, as space is at the center of most considerations.

2. Theories of Time

Architecture and space, on the one hand, and movement and time, on the other, were not discussed in context until far into the 19th century. Pyramids and cathedrals represent attempts, or perhaps the desire, to overcome time. Alberti’s aim to establish a humanistic authority over time is understood as a justification for the rejection of time in his architecture, specifically, for the architect to control and modify it rather than be driven by it. The opportunity to expand time through design, condense the temporal through the creation of architectural artifacts, and, finally, implode or reverse time based on the apparent persistence of the final object implied the ability to build against time. This view emerged from Alberti’s recognition that monumental buildings require a durational approach. According to him, it would take time to guarantee that the materials and building techniques were “suitable” in terms of duration (Trachtenberg, 2005).

Increased production and travel speeds and new technical tools and machines raised the question of a changed relationship between time and space in the 19th century. The overcoming of long distances (compression of space) in a comparably short time by railroads and telegraphy led to the introduction of universal time, replacing the cyclical time concept of the Middle Ages with a gradual linear one—clock time. The increasing mobilization of society that accompanied the automobile and airplane brought about a change in the reception of the architectural environment and its relationship to time and space. Simultaneously with these considerations, Futurists and Cubists abandoned perspective as the generally accepted form of representation of real three-dimensional objects and incorporated speed, simultaneity, movement, and time into their compositions.

Movement was an important theme during the 1920s, and time patterns came into play as different types of movement. A further development of the traditional idea of the spatial sequence, this concept had existed at least since the Baroque period. However, while Baroque architects described the spatial sequence as a series of discrete elements, the space defined by Sigfried Giedion in relation to modernity was continuous (space as path) (Giedion, 1941). Giedion’s principle of spatial penetration is necessary for the perceptional shift from spatial sequence to continuous space; however, subjects in motion—that is, the overlapping movements of spatial penetration—were still missing in his work. In the 1930s, Giedion elaborated this concept in the United States as a modern theory of space, which he understood as a synthesis of an archaic model of space, which essentially starts from the interior, and an ancient model of the exterior spatial realm. The modernist principle of the interpenetration of interior and exterior can, of course, be illustrated very well by the architecture of Neues Bauen; however, it does not refer to the superimposition of frequency patterns or event patterns but is still conceived in static terms. With Cubism, the new optical time period became conscious, leading to the shift away from the perspective conception of space inherited from the Renaissance. The realization of the fundamentally changed conception of space only enabled the understanding of newer architecture.

The self-organizing processes of the formation of forms became the dominant theme of the second half of the 20th century. Logocentrism and reductionism came into crisis. To summarize, this is expressed in the discussion of two questions: what is form—or an object, and what is time? Self-organization is a euphemism for living and, therefore, refers to the biological metaphor of time, to which I will return later. It is not the individual elementary particles, the “components of matter,” but their constellations, their interactions, their synergetic behavior, and their organization that decisively reach an ever-higher degree of complexity. Again, the concept of time plays another key role. In the natural sciences—dominated by mathematics, time is theoretically always reversible, yet Ilya Prigogine (1977) insisted that life and time are irreversible and, therefore, cannot be modeled as mathematical equations.

Given self-organization, other approaches to modeling become necessary. It is not a matter of object models but of those which capture the processual character of a spatial object in the time stream. Sanford Kwinter, in his book Architecture of Time (Kwinter, 2001), studied the conception of time and its relation to artistic forms and, less specifically, to architecture in the second half of the 20th century. He explained therein the transformation of epistemology based on absolute time into the concept of field theory and the idea of the physics of an “event,” theorized against the background of thermodynamics. Thus, he intended to introduce a different idea of time not based on a linear, chronological understanding. I would argue that he only succeeded in doing this by imploding the entire time horizon to the present, a spatiotemporal phenomenon that occurred through the development of digital technologies from the middle of the 20th century. David Harvey addressed the condition of placeless simultaneity as early as the beginning of the 1990s with the concept of time-space compression (Harvey, 1990), which still has an effect today. Different expressions of this current temporal phenomenon can be found depending on the discipline. The following section aims to present the concept briefly but does not claim completeness, as this would exceed the scope of this article.

3. Presentism and Preemption: On Current Theories of Time[1]

The French historian, François Hartog, introduced the concept of “presentism” and described this order of time as an omnipresent present—one in which everything is available, nothing passes, nothing is expected or striven for, and where immediacy alone has value (Hartog, 2015). With this new chronotope (Bakhtin, 1981), the present has become the favored temporal category. “This present is a devouring present,” wrote Christine Ross. “[In] relation to [it] the engendering of historical time seems suspended,” while the future is inhaled into the present (Ross, 2012, pp. 13–14). We can find similar arguments in architectural theory. Here it is argued that temporal distinctions have grown irrelevant in the presence of technological possibilities, in which everything can theoretically be stored, archived, and retrieved within a matter of milliseconds or even nanoseconds (an ever-available past).

Consequently, it is argued that the past, present, and future all equally lead to the dissolution of time and subsequently to “the end of history” (Carpo, 2018), or, at least, the history that Nietzsche defined in the summer of 1873 as wirkliche history. By that, he meant that forgetting is an essential part of keeping the future open, as the past can be “invented” anew, which, in turn, opens up another future (Nietzsche, 2021, p. 611). The omnipresent present that underpins our cultural condition has no beginning and no end, as everything is always accessible, and nothing can be forgotten, as Carpo (2018) pointed out; therefore, it is no longer characterized by the directional vector of historical development, as the vector is entirely eliminated. The problem is that because the present has no temporal horizon other than itself, it only engages in self-reproduction. “Today, we are stuck in the present,” declared philosopher and cultural critic Boris Groys. In his article, “Comrades of Time,” he asserted that “[the present] reproduces itself without leading to any future” (Groys, 2009). Thus, we are confronted with an infinite present, wherein everything is continually evolving, but nothing truly novel is achieved.

The main problem with presentism is that it is an inadequate methodological tool or metaphysical claim for addressing time scales that fall outside of an anthropocentric view of activities and processes on which human activities depend, as Richard D. G. Irvine analyzed very precisely in his book An Anthropology of Deep Time (Irvine, 2020). I argue that the same holds for the micro temporalities (Ernst, 2016) inherent in the operational structures of computational media that affect our everyday lives.

Like these long spans of time, we also deal with the operational logics of technological media, such as preemption, in which the future is anticipated—futurum exactum—and is directly able to act recursively on the present. Most people have experience with preemption through entities such as Google, Amazon, and Facebook, which offer ads for products they did not even realize they wanted—an algorithm made them aware of their desires by preempting them. In other words, one creates a scenario, merely speculative at the outset, which then alters the present. Some scholars have argued that this reverses the arrow of time (Avanessian & Malik, 2016); however, one must keep in mind that an automated and predictable future is initially based on the linear continuity of time, and what is finally reversed is less time itself than the cause–effect relationship that deviates from the rigidity of temporal linearity.

To briefly summarize the broader topic, which exceeds the scope of this article, although contemporary time theories aim to find non-linear temporal models to replace traditional chronology, their performance still adheres to the historiographical model and the narrative ordering of events. This view also applies to Sanford Kwinter’s theory of time (2001), which is based on the dynamic principle underlying the biological model of morphogenesis. For all its pluralistic evocations, his theory on time remains ultimately linear, as immanent differences are constitutively gradual, intense differences that constrict nature and all its parts in their diversification into the (ultimately unbroken) unity of becoming. While I admire Kwinter’s theory, I agree with Georg Kubler that a biological analogy is of limited use for art and architecture. In considering algorithmic technologies, I would like to suggest a theory of time that follows an archaeological mode rather than a historical one. In other words, I agree with Mario Carpo, who questioned the narrative of memory. However, while he did not offer an alternative, I propose a calculated memory, which I will first illustrate through a historical example that offers a different temporal approach.

4. Anastrophic Architecture

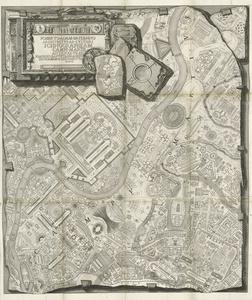

As architects, we are accustomed to projecting a (near) future and proposing alternatives that speculate on the present. However, the reverse is less common. That means, these alternatives derived basically from the present and are based on “what is” and “what has been” as opposed to “what could be” and “what could have been.” The following projects exemplify methodologies that render the prevailing understanding of chronological time untenable by swapping the stages determining temporal directions. For example, Susan Dixon described Piranesi’s Il Campo Marzio as an example of producing new conjunctions of space and time by manipulating chronological time in the engravings of ancient Rome using presentation techniques (Fig. 1). The past became recursive:

I will posit that this way of envisioning the past in the mid-eighteenth century was a necessary leap for a culture that for centuries had made an industry of its past, by having it appropriated, copied, displayed, sold, and restored in a multiplicity of ways and for a wealth of purpose. This new ancient Rome past, more distant and less knowable than the old one, was harnessed as a useful tool for the papal cultural politics of the day. (Dixon, 2005, p. 116)

Piranesi’s interventions sanctified the relics, making the past seem even more distant. The ichnography was “temporally out of synch with the process of historical narration,” Dixon noted. It did not show a specific moment but rather a hybridization of different times, “a kind of uchronia. Some buildings which could never have coexisted at the same historical moment are here rendered peacefully together” (Dixon, 2005, p. 116). Thus, Piranesi illustrated that architectural objects are temporally contingent, impure, and capable of triggering and combining multiple times and temporalities. Certainly, Piranesi’s example dealt exclusively with the vertical dimension of time: the relationships among the past, present, and future within a unified Western history.

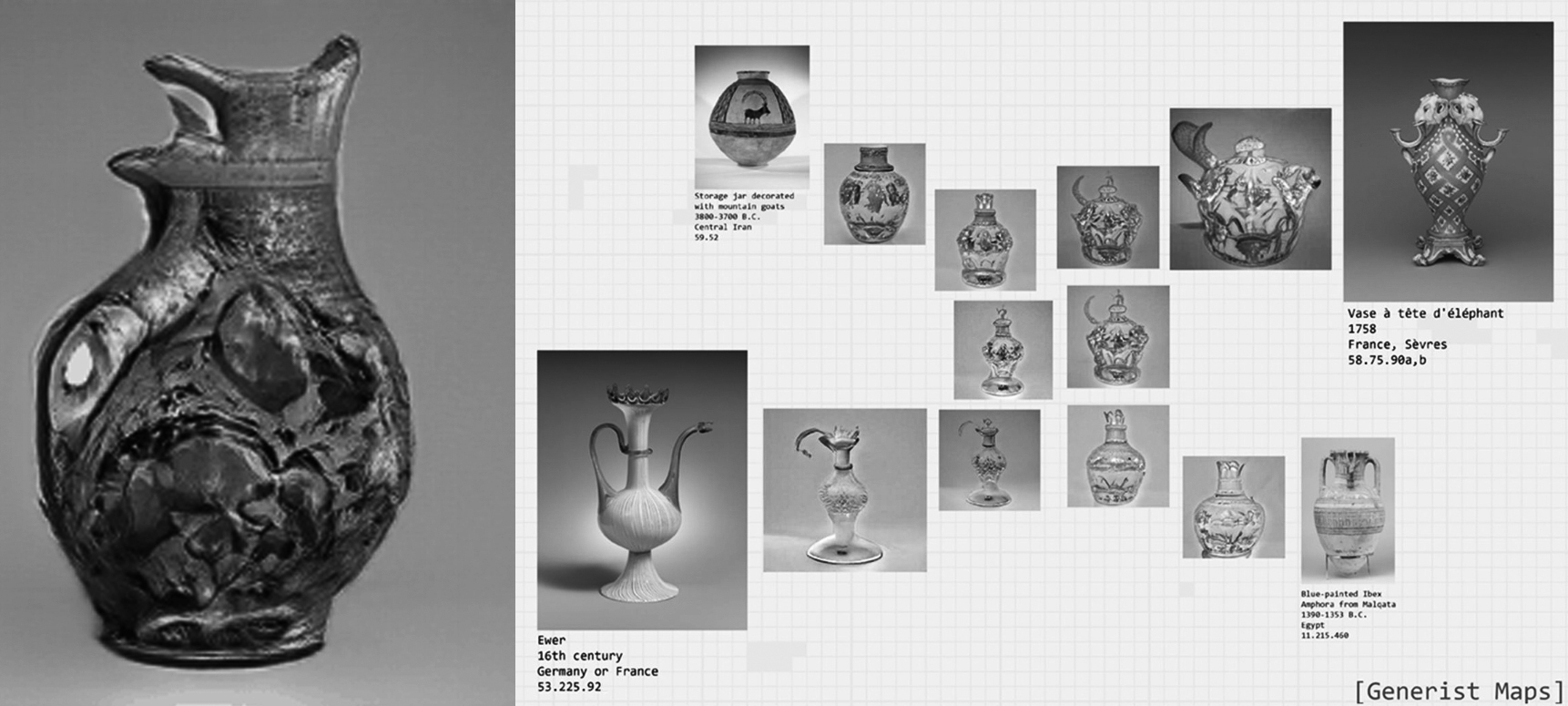

In contrast, a more recent project initiated by the Metropolitan Museum of Art in New York (MET) in cooperation with Microsoft and MIT, which began with a hackathon session in December 2018, also addressed the horizontal dimension of time. The prototype, called “Generist Maps” (Fig. 2), was based on the idea that there is no single (Eurocentric) “art” and that art, created in different cultures throughout thousands of years, is a mutable space (Fenstermaker, 2019; Gen Studio, 2019). The project was based on the following premise: all objects in all the museums worldwide represent only fragments of the art that has ever been created. Not even the most extensive collection can convey a comprehensive picture of art history. Therefore, the objects available to us are metonyms for much larger concepts and ideas. However, with the help of neural networks, it will be possible to speculate about and imagine works of art that may have existed in the past, based on knowledge acquired from works of art that remain. Generist Maps “mark” both existing works of art in a collection and position new speculative objects in between. This project is based upon a resourceful and creative strategy to recapture a missing dimension and appears to be a promising field of scholarly activity.

Based on the knowledge of how and when certain objects existed, an algorithm deduces possible variations on how they might have existed, though they can also be read as objects that could exist in the future. This speculation about and imagining of different items between two known objects yields a contingent object. Nevertheless, Generist Maps is not an attempt to present an all-encompassing art history but to facilitate a more careful look at art, art history, and cultural production. The researchers and curators at the MET are convinced that deep learning can help with understanding collections and objects from points of view that are more aligned with ancient and non-Western ideas of art and image-making. Artificial intelligence (AI) in this context has the potential to challenge traditional ideas and entrenched notions by proposing new configurations and demonstrating how multiple points of view can be considered simultaneously. The resulting recombinant objects open completely new areas of aesthetic research.

Subsequently, in the experiments on the architecture of the city (Fig. 3), I adopted the approach of including the vertical and horizontal dimensions of time. In short, the thesis is that neural networks can reveal new speculative cities present in existing ones but invisible to the human eye. To this end, cities scattered across the globe and embedded in distinct cultural contexts, each with various temporal layers, were hybridized. What makes these experiments so appealing is their dataset: remote sensing technology makes hundreds of thousands of cities available online. A vast collection of architectural and urban forms, spanning millennia, offers a different perspective on what defines human cultural creation to that of a crowd-sourced collection such as Wikipedia, which is biased toward popular architects and art forms, mostly European models. In these experiments, the neural network examines urban configurations and infers the so-called “latent space” between images by speculating about intermediary ones. Computational neuroscientist Sarah Schwettmann, one of the contributors to the Generist Maps project, explained the process as follows: algorithms can extract and internalize the formal features “as well as the historical evolution of collectively, iteratively produced cultural artifacts…and suggest what the rest of that space could look like” (Fenstermaker, 2019).

A close examination reveals similarities to Georg Kubler’s methodological approach but expands the scope of possibilities immensely. In The Shape of Time, Kubler (1962) developed a historiographic model of art that questioned the cultural and temporal restrictions and hierarchies of previous approaches to art history and tried to overcome them. Dismissing the time-mapping notion of progress in favor of more chaotic models, Kubler showed that artistic innovation, replication, and mutation never unfold in a single unbroken timeline. In particular, he criticized the concept of “style” as too monolithic and advocated instead for a historical temporality inherent in art itself.[2] The originality of his analytical framework emerged from his focus on pre-Columbian and Ibero-American artifacts. While doing his research, he realized that the established methods of art history were primarily developed in and for the fields of Western culture. They were not helpful to his work, and this caused him to try an explicitly transcultural approach (Kubler, 1962).

The approach Kubler used emphasized aspects of the artifacts themselves. In his model, art history becomes a story with its own logic: the developmental processes embodied in the artifacts are not limited to specific epochs or regions and unfold discontinuously with numerous and sometimes lengthy interruptions. For Kubler, history is knotted: it changes direction, falters, starts up again, and offers a narrative incorporating connections and detours. In his view, a chronological-linear history based on the presupposed continuity of organic growth and progress can hardly do justice to non-European phenomena. Kubler radically rejected the template of evolutionary biology we find in Kwinter’s theory, as explained above. Instead, he worked to bring the breaks and temporal and cultural shifts into focus. His book explored innumerable ways of understanding the relationship between the past and the present. Instead of using style as a reference point, he employed speculation, detailed observations, and comparisons. In this sense, Kubler can be viewed as being out of sync with time—but not only because of his non-linear history model and his entropic development scheme of a “finite world,” which anticipated approaches that gained currency in the context of globalization debates in art studies during the 1990s.

In today’s global art and communication systems, the consideration that Kubler gave to non-European artistic positions and cultural transfers has become increasingly important. Put differently, the usefulness of an art and architectural historiographical method based on an absolute and linear time needs to be questioned in the context of a globalized world. Historic realism as we know it today is a creation of Western (male) modernity—for many centuries prior to its occurrence, creative depictions ignored proper chronology (Nagel & Wood, 2010). Therefore, neural networks open a completely new possibility for Kubler’s approaches, facilitating consideration of the temporal intricacies at play in all artworks and architecture and enhancing the non-linear time model Kubler developed.

5. Architecture as a Temporal Complexity

Generist Maps and the experiments on the city do not attempt to identify a transhistorical style but rather present a new kind of “montage,”[3] one that assembles various forms, despite time differences, and creates unusual combinations that enable us to speculate about and re-imagine the past and a new and unknown future. This type of seamless montage must be understood as the superposition of fluctuating weaves on a micro-level of formal criteria, creating new art and architectural objects. These outputs can be read as a time complex[4] containing a past invisible to us and an unknown speculative future.

Piranesi’s Il Campo Marzio has been considered a “confused montage of fragments and spaces” (Allen, 1989; Boyer, 1994; Eisenman, 2000) of different tempor(e)alities, synonymous with the beginning of the modern understanding of space (Scully, 1974). Interestingly, to examine multilayered temporalities, montage (as for instance theorized by Benjamin, Warburg, Eisenstein, Didi-Huberman) as a methodology can address discontinuities and complex (sometimes contradictory) interrelationships. In addition to being a design methodology for combining heterogeneous objects, it is also a form of non-linear historiography and critique (Didi-Huberman, 2003). Distinct from the analytical approaches of classical art and architectural history, it is an architectural history that no longer focuses on “great” authors or “great” works. Instead, it is centered on the architecture itself. Georges Didi-Huberman, who conducted a meticulous investigation of Warburg’s project, even stated that “interesting history is only to be found in montage,” which he went on to equate with anachrony.[5] Jacques Rancière made a similar argument:

An anachrony is a word, an event, or a signifying sequence that has left “its” time, and in this way is given the capacity to define completely original points of orientation (les aiguillages), to carry out leaps from one temporal line to another. And it is because of these points of orientation, these jumps and these connections that there exists a power to “make” history. The multiplicity of temporal lines, even of senses of time, included in the “same” time is the condition of historical activity. (Rancière, 2015, pp. 47–48)

In this respect, neural networks offer a new way of “making” history, as Rancière noted, or, as I would describe it, designing time. It is precisely the aiguillages that are significant, and that can be designed thanks to a calculable memory as a seamless transition that is, however, constantly changing, as each specific point can be addressed differently and thus can be entangled and related to different temporalities.

Therefore, while montage has always included a time element, and thus, a polytemporality that adheres to it, let me again clarify the difference between Piranesi’s Il Campo Marzio and the concept of montage of the early 20th century to what I have suggested here. By juxtaposing different temporal fragments, Piranesi produced friction and a provocative argument or meaning (Tafuri, 1987, p. 59). However, it is the dialectical tension produced by exposing the seam that allows the viewer to critically analyze the composition of the various temporalities and reconstruct the friction through intellectual reflection. In short, Piranesi’s “montage” relies on chronology to generate dialectical tension through temporally disparate fragments. The montage presented here, on the other hand, hides the seam and merges the fragments into temporal complexities. The friction does not arise on the canvas itself, as the seam shifts to the conceptual level and prompts the viewer to scrutinize the generated city in the montage, evoking what Carrie Lambert-Beatty (2009) has called parafiction.

Unlike Piranesi, who generated provocative architectural representations by juxtaposing disparate times (by employing an uchronism), I am interested in uncovering what kind of odd time compositions architecture itself creates. Thus, instead of operating with time, as Piranesi did, the formal characteristics of the numerous architectural objects from different cities across the planet are used, regardless of their temporal attribution. The AI thereby draws on Kubler’s theory. The seamless montage, which appears at once familiar and unfamiliar, is created by the neural network internalizing and compressing the formal features of the different architectural pieces created by humans over thousands of years while speculating on the space in between and generating pieces that fit somewhere between existing objects.

6. Conclusion

To conclude, I would like to reiterate that time has a substantial and underappreciated relevance in architecture. However, in architecture, we tend to focus primarily on the transformation of things, objects, and space rather than the mode of time itself. These metrics have become so natural to us that we read architecture, in Panofsky’s sense, using the clear demarcation of epoch styles, thereby privileging the historical and strictly chronological (Western) perspective. However, such a linear conception of history is considerably less useful now, given the current conditions of an intensified planetary interconnectedness.

In this context, the methodological problem raised by Georg Kubler—considered the first global art historian—regains relevancy. The technology of neural networks offers a creative strategy to recapture missing temporal dimensions that are latent in architectural work. Indeed, this approach has the potential to challenge traditional ideas and entrenched notions by proposing new configurations and demonstrating how multiple points of view can be considered. The resulting recombinant objects open completely new areas of aesthetic research.

I have elaborated on this topic in more detail in Untimely Architecture (Mayrhofer-Hufnagl, 2022).

An approach pursued by Aby Warburg and, later, Peter Osborn.

Martino Stierli’s (2019) book provides a comprehensive explanation of the distinction between montage and collage.

While Peter Eisenman speculated on time in architecture in various works, I would like to highlight his recently published book Lateness (2020), in which he discussed temporal ambiguity. This concept is particularly revealing in its comparison to Robert Venturi’s complexity of form and underscores the current paper’s argument. Eisenman explained how “complexity had become an important critical tool after the modern,” and in so doing, Venturi looked both “forward and backward in time.” Eisenman then argued that “in today’s context, however, the digital facilitates the production of complexity,” thereby losing its usefulness as a critical tool. Through “advances in digital software,” he wrote, “contemporary architecture produces increasingly more exuberant forms, each one just as anomalous as the last, creating a conceptual milieu that is ultimately homogeneous.” He concluded by stating that the critical mode no longer lies in the creation of complex forms but in a temporal complexity nested within the concept of lateness.

“anachronism, a montage of different temporalities” (Didi-Huberman, 2003, p. 81).

_trained_on.jpg)

_trained_on.jpg)