1. Introduction

Architecture, urban design, and planning in African cities are currently produced based on the notion of permanence and linearities of spatialities, which contrast with the constantly mutating and non-linear nature. Spatiality denotes a socially produced space and a product of the political and economic system that exists primarily in the dimensions of time (Massey, 1994; Sheppard, 2004). The resulting spatialities appear to contrast with the ingenious local practices. Linearity in planning embodies the Cartesian grid that shaped the modernist sub-divisions of land and top-down planning.[1] The grid on an urban scale is reductionist and hardly responds to local contexts and the embodied multi-layered complexity. The paper explores the emergent spatial dynamics and self-organization processes of urban growth in post-colonial African city, using Onitsha markets as a case study. It also aims to provide insights beyond the permanent and linear spatial configurations of the built environment. Onitsha is a city in southeastern Nigeria driven by an urban market phenomenon and currently, the third largest urban area in Africa, trailing behind Cairo and Lagos. The markets in Onitsha appear in almost every corner of the city and manifest as constantly adaptive, periodic, and incremental forms of spatiality, which are shaped by the flux of material flows, contextual forces, and contestations in the city. Traditionally, markets are important sociological landmarks for the understanding of human relations in the city. Earlier scholars provided a technical definition of markets, as a public concourse of buyers and sellers of commodities meeting at a place more or less strictly defined, at an appointed time, and often within a neutral territory between societies (Hill, 1966; Hodder & Ukwu, 1969). They are defined by morphology, operations, access, economic activity, relational condition, and geography (e.g., Ahia in Onitsha, Suq in Cairo, Markt/Marché in Brussels). Markets are seen as the essence of metropolis (Braudel, 1992; Calabi, 2004), as spaces for resistance and mobilization against gentrification, (Gonzalez & Waley, 2013), and as a hallmark of urban life in African cities (Ikioda, 2013; Kinyanjui, 2019). Markets engender diversity and socio-economic life in cities (Janssens & Sezer, 2013; Watson, 2006). They reflect an ephemeral landscape of transaction (Mehrotra et al., 2019), which operate on the edge of urban conditions (Mörtenböck et al., 2015). Urban markets are also linked to various issues, such as food security, urban renewal, access to public space, cultural heritage and tourism (Seale, 2016). They are infrastructures of multi-level exchanges and material flows in cities (Chukwuemeka, 2022).

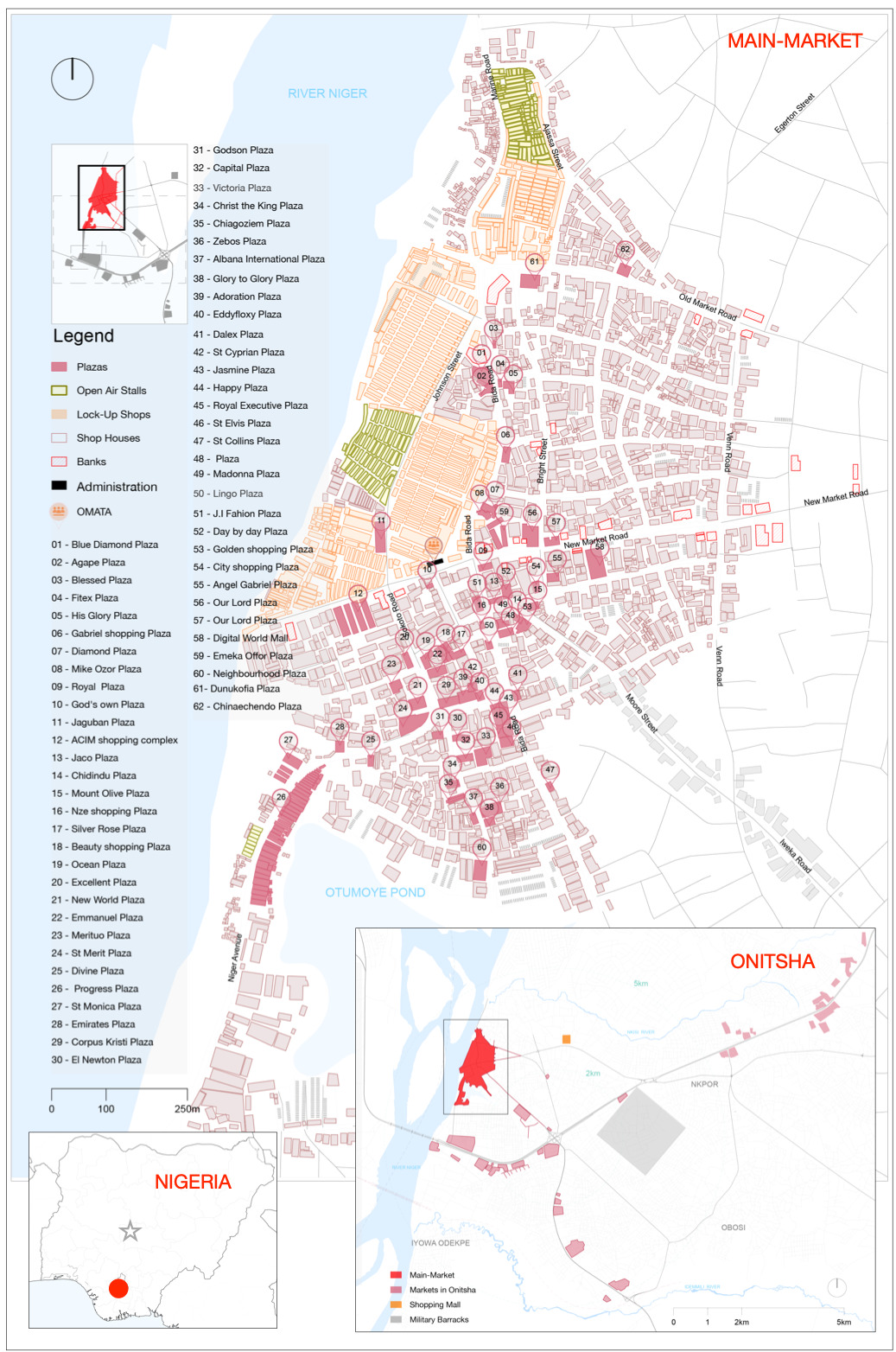

Through observations, mapping, surveys, archival research, and ethnographic readings of the Main-Market in the city (the largest site among 44 different market clusters in Onitsha) (see figure 1), it was apparent that markets in Onitsha reveal alternative ephemeral and non-linear forms of spatiality, which are shaped by the space-time cultural logic embedded in a contextual specificity of the Igbo ethnic nationality in Nigeria. In this paper, I argue for the need to recognize these forms of spatialities that reflect the organic mechanism of spatial productions across spatiotemporal scales, which are often devised by citizens as ways to cope and claim rights of access to the city. In this case, the ephemeral epitomizes an ontological permanence of spatial productions, amidst extreme otherness and uncertainty in the city. The second section of the paper introduces Onitsha markets in Nigeria. Sections three and four present a critique of permanence and linearities within the disciplines of architecture, urban design and planning in post-colonial Africa, respectively. The paper is concluded with arguments on the need to develop tools and frameworks that reflect the complexity of the local context, and towards livable urban growth.

2. Spatial Configurations at Onitsha Markets in Nigeria

2.1. Ephemeral Spatialities at Onitsha Markets

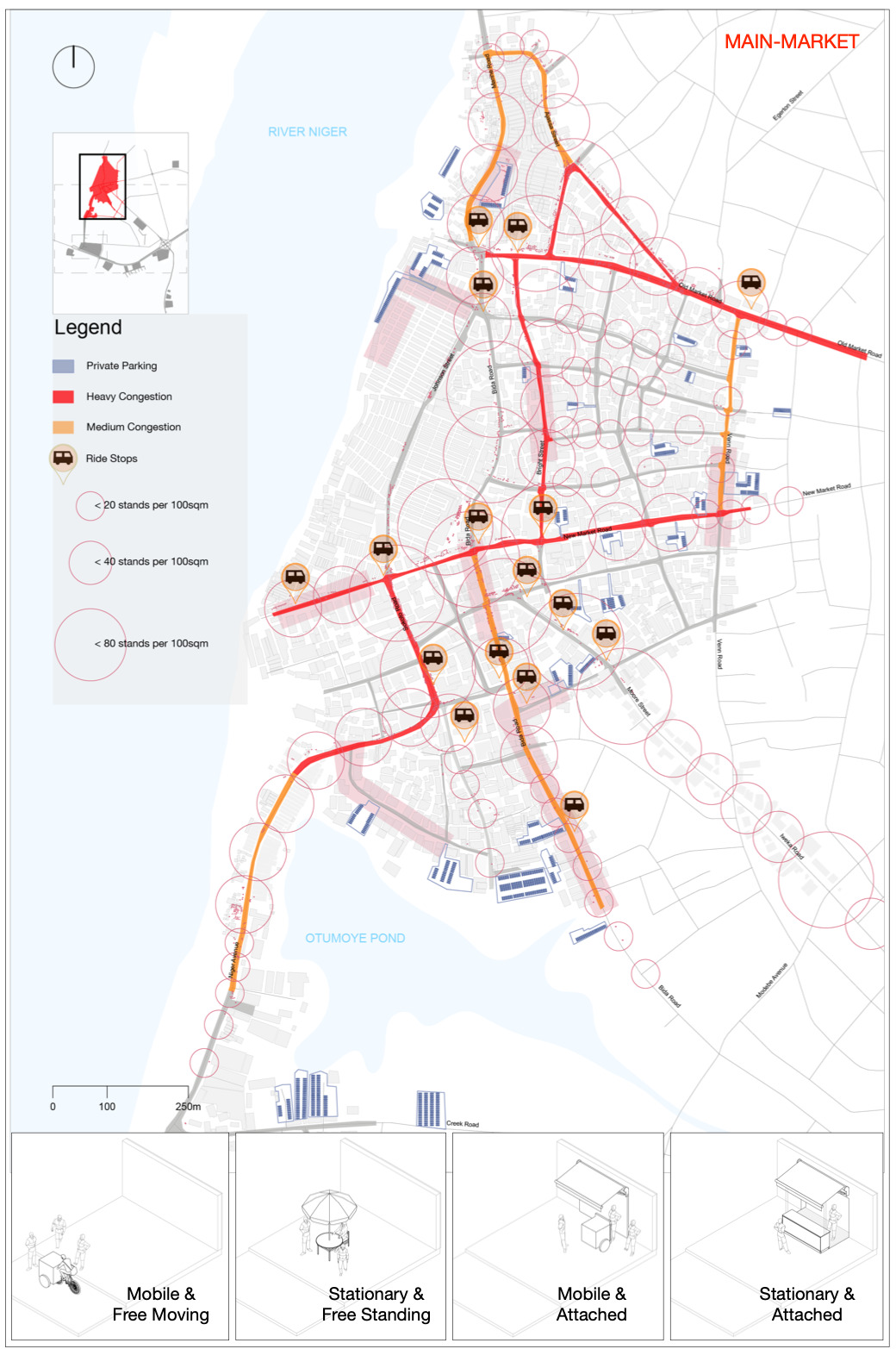

Ephemeral spatial appropriations at Onitsha Markets symbolize the survival adaptive mechanisms amidst precarious tenure conditions in the city.[2] They account for most trading areas in Onitsha, in response to the uncertainties emanating from exclusions (e.g., eviction, demolition, or seizure of goods). Ephemeral spatial appropriations at Onitsha denotes a way of producing space under uncertainty, which occurs under improvised, periodic, adaptive, and incremental mechanisms (see figures 2 and 3). They are found in almost all corners of the market locations in Onitsha, including segments for merchandise, transportation stops and administrative building of the umbrella body of merchants known as the Onitsha Markets Amalgamated Traders Association (OMATA). Ephemeral spatial appropriations vary from the itinerant traders carrying goods on their heads or with wheel-carts, to the stationary traders with parasols, which could be freestanding or attached constructions to adjoining buildings. These appropriations are often allowed within the market sites by OMATA because the ephemeral traders provide symbiotic services such as food vending, which also limits potential conflicts between shop owners and ephemeral traders. The various identified spatial forms are developed in an evolutionary sense, and exhibit examples of building adaptations while being subjected to constant modifications by the occupants as a function of constant flux of materials through time.[3] Four categories of ephemeral spatial appropriations have been identified at Onitsha, which are mobile and free moving, mobile and attached, stationary and freestanding, and stationary and attached. Attached appropriations (either mobile or stationary) allow the ephemeral trader to attach oneself to a shop, a fence, or a building under a symbiotic and complementary arrangement with the host. In such a situation, it could be a tabletop in front of the shop, rented from a shop owner by a tenant who is invisible to the government. Mobile and Free moving units are facilitated by different forms of carriage mechanisms. They are mainly pedestrian itinerary hawkers in search of a better location or avoiding potential disruptions from state actors within the vicinity. Whereas Stationary and free standing is when there is a fixed infrastructure like a kiosk but allows for different and constantly changing users. Stationary ephemerals concentrate on a particular commodity in the different sections of the markets.

2.2. Igbo Fractal Cultural Logic

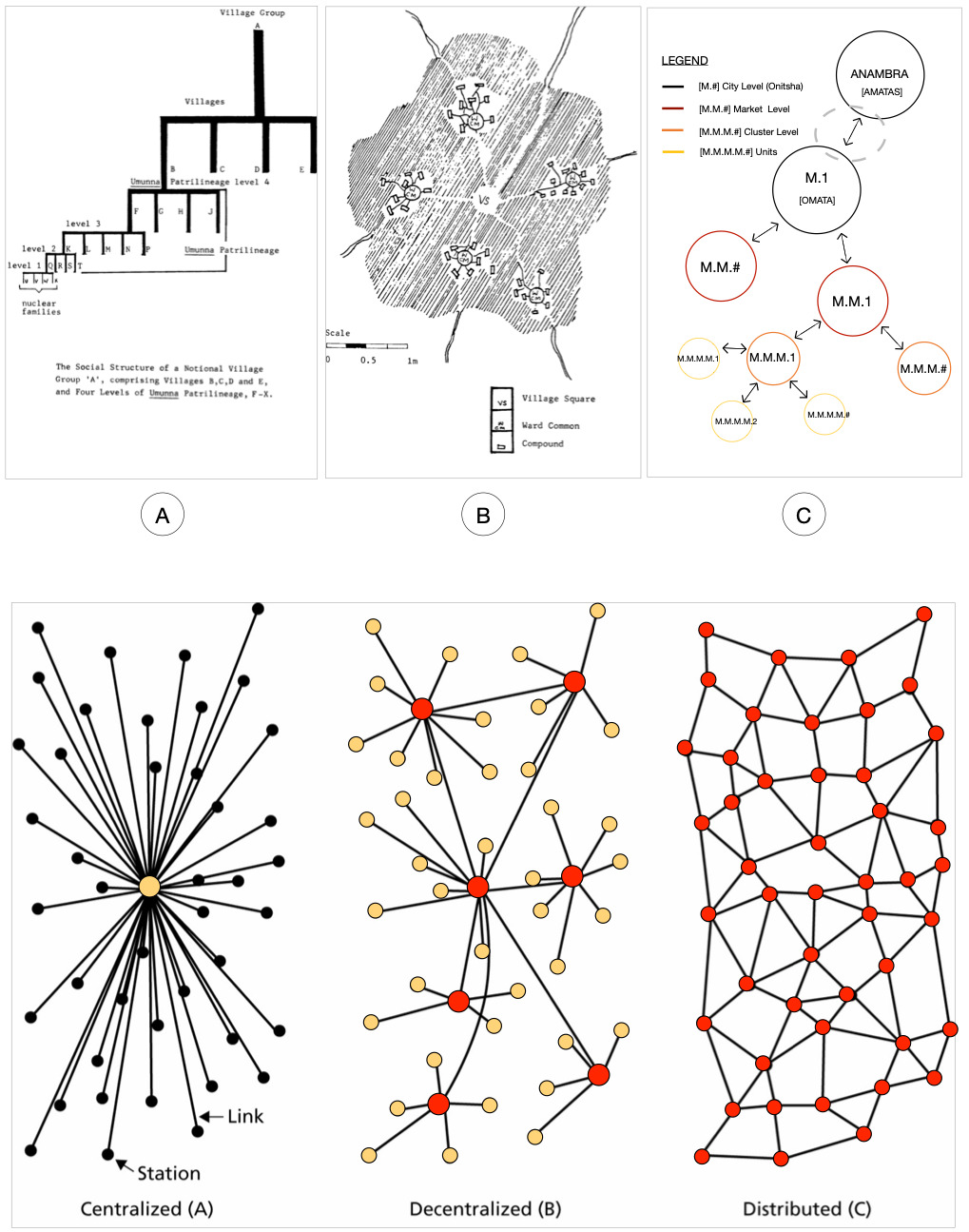

Spatial configurations in Onitsha reflect the networks of market traders’ associations with defined ephemeral territories. I made a striking observation on the fractal cultural logic among the Igbo at Onitsha after looking at the ancestral socio-political unit (family), ancestral socio-cultural units of space (settlement), and contemporary socio-economic units (market organizations), in this case, OMATA. This fractal cultural logic among the Igbo permeates every facet of social life, including social relations, and the production of space (see figure 4). Fractals are mathematical concepts characterized by the repetition of similar patterns at ever-diminishing scales found in naturally occurring phenomena (Batty & Longley, 1994; Eglash, 1999; Mandelbrot, 1982). The fractal logic in Onitsha reveals indigenous knowledge systems and spatialities that are different from the current alien planning logic of extreme Otherness used to in shaping the post-colonial urban Africa. Although the physicality and infrastructures in Onitsha markets appear chaotic, on a macro-level however, one can observe an emergent infrastructure of people as networked fractals of spatiality. Baran (1964) presented three types of networks in a dynamical system; as centralized, decentralized and distributed networks. These network configurations provide a lens to visualize the immensity of the Igbo fractal phenomenon in Onitsha. Fractals have been applied in the reading of cities to understand the morphology of cities under architecture and urban design disciplines (Batty & Longley, 1994; Bovill, 1996; Frankhauser, 1998). However, these studies were not extensive on the cultural foundations of the fractals in shaping spatiality. It is culture that produces the physicality as seen on the African continent with remarkable examples of fractal spatial forms and structures (Eglash, 1999). The fractal logic of organization is found in socio-cultural, socio-economic, and socio-spatial aspects of the Igbo society, but is currently not visible in the physicality of Onitsha. The British colonial regime in Nigeria destroyed the fractal logic of spatial productions among the Igbo with the Township Ordinances (Home, 1983, 2019).

3. Beyond Permanence

3.1. Periodic, Adaptive, and Incremental Appropriations

The Igbo believe that no condition is permanent, and there is constant change in the world (Achebe, 2012).[4] Periodic, ephemeral, adaptive, and incremental appropriation in Onitsha denote a way of producing space under uncertainty, and reflect the fluid territorial definitions of spaces in the city. These forms of appropriations in markets have cultural origins and antecedents based on Igbo rest days (four-days for the small villages, eight-days, or sixteen-days for the larger village-group settlements). Ancestrally, daily markets were periodic and typologically distinct (Aniakor, 1978; Nsude, 1987; Okoye, 1997). However, in contemporary Onitsha, daily markets are defined by a seven-day calendar week, hour-cycles, and festive days. Ephemeral trading has a local name, 'Oso Ahia’, which literally translates to running markets. Oso Ahia is a market activity that produces transitory spaces from the way traders respond to how goods move in the markets. Ephemeral appropriations in Onitsha demonstrate how cultural and contextual realities of time-space interpretations shape the nature of spatial configurations of place. See narrations by some traders who operate as ephemerals in the markets:

Itinerant Vendor 1 — Beverages (Translated to English from Igbo)

“I carry my products around the market. They know me well here, so I don’t pay anyone. But in some places, they might ask for a ticket. The location depends on what is happening in the city. Some days when there is traffic on the expressways, most of us choose to sell to travelers. They are often thirsty and hungry and need our products. I receive my supply on credit from the warehouse and will balance my sales at the end of each day or the following morning. My supplier is a wholesale retailer for the beverage company. The serious challenge is the environmental Taskforce. They differ from the ones that check on the drivers. These fellows claim they are sanitizing the streets. But we know how to beat them. My friends are currently around Upper Iweka Junction, and we send ourselves messages to alert everyone each time we spot them. I am saving money so I can someday rent and own a shop. Possibly, I will be importing goods from China to sell.”[5]

Itinerant Vendor 2 — Food (Translated to English from Igbo)“I come out on weekdays from 12 noon to 3 O’clock p.m. to sell my Okpa (local delicacy). Then I will use the money to buy food for my family. I wake up early between 5 - 6 O’clock a.m. to prepare the food and everything. Some days, when business is bad, I carry the remaining items home because there is no place to keep it. Moreover, it will spoil. So, we eat it at home for that day.”[6]

3.2. Beyond Permanence

Permanence appears as the defining prejudice of the modern architecture profession, and generations of architects and patrons who imagined the artistic merit of their buildings as their legacy to posterity have nurtured this prejudice (Chattopadhyay, 2019). Claims of permanence also define the mechanisms of exclusion used in the colonial logic of planning, as seen in Fredrick Lugard’s Township Ordinances in Nigeria (Home, 1983), whereby deviations legitimize spatial dispossessions of millions across the world (Chattopadhyay, 2019). Mehrotra and Vora (2021) questions the false notion of permanence as the univocal solution for urbanities, which often differs from the organic constructions of spatiality outside the purview of the State, and massive shifts in demography occurring around the world.[7] These forms of spatial productions point to an urbanism, which leverages on the fluidity, ever changing flux, as a survival mechanism in response to precarious tenure conditions seen in Onitsha. In debating urbanization in the developing world, Unruh (2007) contends on the need to resolve the acute tenure insecurity as a fundamental way of improving the conditions of impoverished and segregated settlements. The often quick-fix approaches, such as forced evictions, often lead to the destruction of social networks and physical assets of citizens. Post-colonial architectural practice in Nigeria has an obsession with the idea of the city as centralizing spectacles as part of the colonial relic of the command-and-control planning structure.[8] One of the unintended consequences is that these cities become characterized by incessantly provisional intersections of spatial appropriations that operate without clearly delineated notions of how the city is to be inhabited and used (Simone, 2004). The current ephemeral spatialities in Onitsha demand a re-evaluation of existing planning frameworks which recognize this category, and employ the embodied agency and inventiveness. For example, how can architects and planners work with time, as a potential pathway to the engage with the exclusion in the city and making a case for an open, evolutionary architecture and urbanism?

4. Beyond Linearities

4.1. Fractal Urbanities and Spatialities

Many patterns of nature embody a fractal geometry that is different from the modernist Cartesian grid. Mandelbrot’s Fractal Geometry of Nature (1982) demonstrated the potential practical applications of such geometry to diverse fields. However, the phenomenon of fractals is not an entirely new construct, as they are ancestrally embedded in the architecture, arts, and settlement patterns of most African societies (Eglash, 1999). They are often in the form of ever-diminishing forms of dwellings (circular or rectangular), or pathways, which reveal indigenous knowledge systems. Eglash (1999) outlined five important components of fractal geometry which are:

-

Scale: which refers to the attribute of having similar patterns at different zooms of scales.

-

Recursion: which implies that results are repeatedly returned, as a feedback loop and in constantly repeated iteration.

-

Self-Similarity: which implies that there is self-replica of the whole, at most of its parts.

-

Infinity: which means that it is continuously self-replicating

-

Fractal Dimension: which allows dimensions to be in fractions.

The fractal phenomenon in Onitsha markets exhibits most of these components except to the infinity because it is not, in this context, understood as mathematical phenomenon. This is where the critique of architects using the concept of fractals from some mathematicians is the strongest. For example, Ostwald (2001) on the attitude of architects and the conscious attempts to use fractal geometry to create architecture after Mandelbrot’s (1982) publication. Ostwald & Vaughan (2021) further argue that no building or architecture in the real world can ever possess true fractal geometry because it only exists in mathematics, and hypothetical examples such as computer simulations and philosophical puzzles. The reason given was that the concept of fractals in architecture is devoid of this infinity with a physical scaling limit, whereby the self-similarity breaks down completely.

Although one could agree with these critiques on how architects mimicked fractals in their designs, however, the epistemological position on what constitutes fractals in a built environment can be contested with evidence from the African continent. Also, the focus on infinity of scaling does not consider that some fractals occurring in nature, such as plants, animals, snowflakes, do not exhibit the expected physical infinity. Mandelbrot’s (1982) central idea of fractals is on the practical applications, using this type of geometry with its repetitive-diminutive or repetitive-expansive logic and not only on the theoretical proof of the infinity of the logic. The work of Ron Eglash (1999) provides evidence on the fractal dimension of architecture and settlements within the African context, which are not arbitrary, but consciously generated by cultural logic and practices within a contextual specificity. Fractals could be the starting point for future analysis of the physicality and processes of spatial configurations in the African city. On recognizing the utility of fractals and its applications for non-linear spatialities, Batty and Longley (1994) acknowledged the various limitations of Euclidean geometry to real-world systems, which could be substituted with more appropriate geometry of fractals for simulating real world complexity.

4.2. Beyond Linearities

The current mode of spatial productions mandated in contemporary urban Africa is mostly based on Euclidian ideals (of gridiron, radial, and triangular ordering of space), rooted in linearities, and often without reverence for context. Conversely, fractals embody non-linear emergent forms of everyday spatial productions with high dimensionality, as observed in Onitsha. Among the Igbo, Ala adighi akwu oto, which literally translates to “land and its borders are never linear.” It is a philosophical critique of the linear conceptions of spatial productions. The fractal spatialities in Onitsha markets differ from the simplistic top-down planning principles imposed on the city. Nicholas Nassim Taleb (2012), in his critique of modernistic top-down (irreversible neomania) approaches associated with the architecture, urban design, and planning disciplines, espoused the importance of embracing high-dimensionality of fractals:

“There is some evolutionary warfare between architects producing a compound form of neomania. The problem with modernistic - and functional - architecture is that it is not fragile enough to break physically, so these buildings stick out just to torture our consciousness - you cannot exercise your prophetic powers by leaning on their fragility. Urban planning, incidentally, demonstrates the central property of the so-called top-down effect: top-down is usually irreversible, so mistakes tend to stick, whereas bottom-up is gradual and incremental, with creation and destruction along the way, though presumably with a positive slope. Further, things that grow in a natural way, whether cities or individual houses, have a fractal quality to them… Everything in nature is fractal, and rich in detail with a certain pattern. The smooth, by comparison, belongs to the class of Euclidian geometry we study in school, simplified shapes that lose this layer of wealth. Alas, contemporary architecture is smooth, even when it tries to look whimsical. What is top down is generally unwrinkled, (that is, unfractal) and feels dead” (Taleb, 2012, pp. 324–325).

Many useful insights could be drawn from the ephemeral and non-linear appropriations of spatial productions in Onitsha. In linear contexts with relatively stable and predictable outcomes, the challenge is often mechanistic in such that problems are clearly defined and broken in smaller structures and solved using available knowledge best practices. However, in non-linear contexts, with unpredictable outcomes, the challenge is high dimensional and emergent. This is because little is known about the challenges, and engagement requires explorative thinking across scales, whereby micro-scale interactions could trigger second-order effects. Spatialities beyond the permanent and linear configurations could provide insights on how to deconstruct, disassemble, and reconfigure for an urbanity in a state of constant flux in contexts amidst uncertainty.

5. Conclusion

The paper presents a critique of epistemological permanence and linearities on spatial productions in post-colonial African cities to reflect urban mutations, rapidity, and scaling challenges, as seen in Onitsha. Spaces are appropriated in ephemeral way, used collectively and periodically, and transformed incrementally to deal with uncertainties in the city due to precarious tenure and exclusion in the city. The challenge is how these observations could be reflected in both pedagogy, policy, and practice. For example, how can ephemerality be used to rethink spatiality and access to the city? What forms of activities require permanent configurations? How can street design, zoning, urban scaling, and structuring of spatiality in the city be structured to reflect the context? There is a need for alternative frameworks and tools to rethink tenure, augment the already existing autonomous practices in the city, and to address the seeming crisis of complexity from an interdisciplinary perspective, and towards a livable urban future.

On the grid as the defining tool in the making of North American cities, see Gandelsonas, M. (1999). X-urbanism: architecture and the American city. New York: Princeton architectural press.

See Oxford Learners dictionary definitions:

Ephemeral — lasting or used for only a short period of time.

Temporary — lasting or intended to last or be used only for a short time; not permanent.

Permanent — lasting for a long time or for all time in the future; existing all the time.

Temporality is time dependent, defined, also not autonomously existent, nor randomly operational.

See Brand, S. (1995). How buildings learn: what happens after they’re built. New York : Penguin books.

The Igbo believe that art, religion, and the whole of life is embodied in the art of the masquerade. Life is dynamic, and not stationary.

Excerpt from interview conducted on 13 August 2018.

Excerpt from interview conducted on 13 August 2018.

Mehrotra’s (2021) uses the kinetic city to describe an urbanism of flexibility, where openness prevails over rigidity and flexibility is valued over rigor.

An example in Nigeria is Festac '77 during the 1970s. The most recent example on the city scale is the capital of Nigeria, Federal Capital Territory, Abuja. See (Monroe, 1977).