1. Introduction

After the break with the Vitruvian tradition and under the ground-breaking principles of the legacy of the German thinker Gottfried Semper in his work The Style (1879), with which the spatial envelope becomes the essence of the architectural configuration,[1] it is with Bruno Zevi (1958) when the modern interpretation of this discipline is reached, as the art of space, constituting the void or the confined space in the raw material of the architect. This is how the numerous theories of aesthetics born at the end of the 19th century define it (Calduch, 2012).

The architecture of the tobacco drying sheds developed in Granada (Spain) during the 20th century, is a visual and tactile experience with which to glimpse the traces of the historical trace and its correspondence with the individual and biological personal time of the observer, i.e. the geometric chronotope. This novel conception of observation linked to time and place leads to innovative explorations in the field of architectural contemplation of this landscape context.

The territory under investigation, known as the Vega de Granada, is located in the south of the Iberian Peninsula and more specifically in the centre of the homonymous province. It is configured as a vast and perfectly delimited extension, covering a total of forty-one municipalities. The geographical diversity of this Vega, defined by an enormous horseshoe-shaped plain protected by a forceful mountainous topography, generates a diverse landscape, full of systems and sub-systems; an endless territory on which a tight tapestry of small plots is superimposed, crossed by roads, paths, rivers, irrigation channels and irrigation canals. For this reason, for our study, we must refer to Geography as “a fundamental discipline for the knowledge of any specific territory” (Sauer, 2006).

2. Objectives

Architecture is a discipline with an evident link between spatial relations and temporal relations intertwined through form in a given place. This is what we are referring to when we use the term chronotope (Álvarez Agea & Zazo Moratalla, 2020); by incorporating the words geometry[2] or typology[3] into this concept, the etymological meaning is redirected towards the study of traces or marks in time. Based on these premises, the incorporation of new concepts such as the geometric chronotope and typological chronotope is justified as the basis for the connections between space-geometry-territory and space-time-formal typology or form respectively, as architecture is a topical discipline that cannot ignore the terrain on which it is based. On the other hand, the historical nuance that includes the dimension of the historical architectural chronotope is also linked to the architectural experience that is developed below and which aims to justify the need for a new consideration of the industrial architectural legacy of the city of Granada.

The historical architectural chronotope always appears as a binding tool capable of linking physical time, the biological time of the human being and memory with the place. It thus becomes the bearer of the zeitgeist,[4] which allows a gradual change of space in time thanks to the meaning of site (Iovlev, 1997).

In this context, the main objective is focused on demonstrating, from the guided chronotopic analysis and the enhancement of the geometry of the architectural prototype of the tobacco drying sheds as a result of its temporal footprint, the radically essential condition of these industrial models in the heritage legacy of the architecture linked to this cultural space.

With the choice of the so-called zero architecture model (Sobrino Simal, 1998), in which the houses for curing tobacco are represented, we have chosen its attribute of a strong and invariable fixed geometry that manages to configure an entire region as a reliable typological chronotope, which generates a historical trace of rich and unequal readings in different epochs.

3. Methodology

As a first approach, it is necessary to identify the physical characteristics of the specific area in order to determine the geographical and morphological characteristics of the place, in order to subsequently undertake the ethnographic exploration of the community that inhabits it.

Based on the interpretation of geometry and form as an architectural trace, the condition of the tobacco-drying shed as a historical chronotope capable of linking physical time with the vital time of man and memory in the place is argued, using a qualitative methodology of induction.

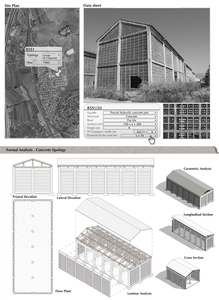

In order to manage the data, the first step is the territorial analysis of the Vega, programming tours over previously planned sectors based on the visual and conceptual qualities of the buildings and the delimitation of areas defined by their landscape conditions: properties and pieces of land, riverbeds, roads, irrigation canals and geographical features (Fig. 1).

As a tool with which to organise the database obtained, a repertoire of templates is configured in which the invariants that constitute the structuring guidelines of the hypotheses put forward are collected. The establishment of the structuring guidelines together with the constructive characterisation are defined by the elements inherent in the configuration of the chronotope: space, time and form (Bakhtin, 1999).

Subsequently an inductive method of synthesis is applied to the structural units, series and categories defined, which allows for a selective and individual analysis of the buildings chosen from each of them, determining their entity and their particularities, as well as the elements and external agents that make them up. It is a rigorous, versatile and simple form of territorial exploration, of knowledge of industrial architecture as a distinctive agent of an era (Sobrino Simal, 1998), of discernment of its endemic condition and of the proliferation of an architecture that favoured the conquest of the whole territory.

The systematic organization of the contents obtained during the different analytical studies of the landscape comes from the grouping and coordination of knowledge after a previous discernment in different categories, a consequence of the application of the a priori theories concerning it. All of this results in an exact approach to the study of the landscape of the Vega, predominantly from the geographical perspective, along with the help of other empirical sciences, as well as others of ethnographic character which explain the close relations between the human being and its local architecture.

The morphological method fits perfectly in this field of research.

4. Discussion

4.1. Abstraction in tobacco architecture

In architecture, abstraction represents an inquiry into the essence. It is the search of what constitutes, in the architectural work, the nature of things and what always remains. Thus, it represents what is considered as truly important, unaffected by the temporal changes attributed to each living or inert entity.

One of the primary characteristics of the 20th century was the triumph of abstraction over mimesis when the latter is considered a metaphor, comparison or imitation of nature (García Nofuentes, 2017); in other words, the rise in the use of an intellectual operation equivalent to isolating, instead of producing a conscious copy of nature. This enables the process of abstraction to become a new method to generate forms, and which elevates rationalism to the category of essential discipline in architecture and art, and certainly of general thought, as commented in Critique of Practical Reason (Kant, 1961).

Abstraction represents the rational power and the most characteristic, synthetic and renovating intellectual and formal impulse of all the arts developed throughout the 20th century (Berger, 2005). Unlike the corset imposed by mimesis, abstraction follows the footsteps of the safety of the past, the faith in progress, the significance of the future, rationality and the innovative new forms of knowledge outside the realm of time.

Basically, abstraction is understood as any mental operation in which one separates a quality or characteristic that would be impossible to carry out physically.

When referring to architecture alone and its essential condition of endurance over time, we have chosen, under a formalist perspective, a strong type of building capable of entering mass production in the territorial conquest, thus reaching its condition of geometric chronotope. This means that the form leaves a footprint in the place (or topos), which enables us to identify the time of nature and the time of human biology.

Under the consideration that architecture manifests itself through its praxis and reality, there is a very clear fact: it is attributed above all the capacity to organise, to propose an order which, although it may be complex, must in any case be recognisable thus offering a precise explanation of the differences between the circumstantial factors of its creation and its essential issues. According to this author, the more abstract architecture is, the more detached it appears from all the contingent dimensions that surround it, such as its immediate practical utility, the resources employed to build it, or the social, political, or religious meanings temporally attributed to it (Martí, 2000).

In the approximation of the concept of abstraction to the vernacular industrial architecture of tobacco, a sensitive closeness of ideas can be seen. Possibly one of the greatest attractions of this symbol of the heritage of the province of Granada (Spain) is probably its specific architecture, for which it is necessary to understand the purpose of its construction, very different from any other building unrelated to the tobacco industry. The exclusive function they are meant to perform in their respective locations allows them to acquire features that resemble the essence of architecture, the integrity of the concept when practicing an exercise of abstraction. Only space, form and skin mark a territorial footprint in time. Built with the sole purpose of shaping a space with certain environmental conditions, they constitute architecture in its maximum degree of simplicity and purity.

4.2. Invariants

Invariants are defined as basic singularities which are key for architecture to exist and which are obviously conveyed by the architecture of tobacco curing. That way, the aim is to detect those qualities that are crucial in any building regardless of styles, uses, economy, social conditions, culture or specific construction elements (González Ruiz, 2004).

The invariants refer to the type of architecture in which the elements themselves lose importance while what the relationships are highlighted. They refer to works of architecture whose meaning resides in the entity of these relationships, in their intimate qualities and their profound conception, but never in the individual value of the different elements that compose it.

The investigation of the essence as an architectural property transports us to the guidelines used for these constructions in the province of Granada, which are clear examples of architecture stripped of the unnecessary.

These properties, intrinsic and essential, existing without exception, immutable, generic, present in any architecture whatever its character or use, are conceptualized as invariants; they are recognisable in the drying sheds and we consider the grouping of their principles into five categories: materiality, space, geometry, topos and chronology.

In the following section we focus specifically on three of them, because of their importance in the concretion of the meaning of chronotope and the relationship with the trinomial: geometry, space and time.

5. Results

Once the field inspection work had been completed, in which more than 400 drying sheds were recorded, the information collected was screened according to the formal, structural and dermal analytical principles proposed in the method chosen for this research. Once classified within the scope of the planned routes (Fig. 1), the resulting data are structured in the templates drawn up for this purpose, one example of which can be seen in (Fig. 2). The comparison between them allows a discussion to be established that responds to the objectives established throughout the study.

5.1. Geometry and matter

All matter has to acquire a certain form.

Presence and permanence are attributes that guarantee the architectural footprint in space and time. The durability of the formal definition, despite the physical alterations of matter and appearance caused by time, guarantee existence. The connection between the momentary variabilities of appearance create temporal relationships and links that shape the essence of being. “Only through duration can we perceive change as an experience of difference” (Deleuze, 2002 in Álvarez Agea & Zazo Moratalla, 2020).

In order to manifest itself and become truthful, every material entity must have an aspect, an external figure, and it must be configured in the dimensions of reality; in this way it will acquire the tangible properties that are attributed to substantiality and consequently to the architectural object.

Form, figure and geometry are terms with similar meanings and very similar popular nuances. Natural matter acquires a definite form, of a casual nature, from the principle of uncertainty, attributable to chance or to the eventuality of forces, conditions and pressures of a spontaneous and natural order. But the matter used in architecture takes over the quality of geometry, whether regular or irregular, and is considered as one of the essential visual properties of form.

Geometry and its constancy in time is the only essential architectural characteristic capable of guaranteeing a particular permanence that also allows change. It is what Gombrich (1983) defines as formal structure: “that which remains constant in spite of the change of aspect”, that is to say: the geometric form is the basis of architectural identity.

5.2. Space

In Arquitectónica (1999), the philosopher José Ricardo Morales shares reflections on temporality and purpose as necessary ingredients of the architectural work. He introduces new conjectures about the conception of exact space or absolute space, a space without any kind of impurity of known origin: surroundings, sensations, geometry and proportions. This concept, which he calls abstract space, makes it possible to separate the limpid and essential space from perceptible space, placing it in turn in relation to the place, of which it is a part. The first definitions of discernment between the abstract and the concrete are thus established as two senses of the same idea in which ontological time is always present. According to Morales (1999, p. 174), Architecture does not model space, among other reasons because space is not a real and perceptible entity, but an abstraction that can be made from very different fields of thought and on the basis of countless assumptions. Therefore, it is not space but the spatial or extensive that is modified, which is something very different.

Outer space, with all its indeterminacy, is considered as a universal, general and indefinite extension, it does not contain any concrete reference, it has no defined human gesture, nor does it register any trace other than that of nature itself. As Morales (1999) warns, in this condition the concept of space does not really exist, since it is still a concept created by man; there is only indefiniteness: “[…] Man errs in the indeterminate; […] indeterminate is that which lacks traces, data, signs, notes, limits, lines or points of referral, of reference.” (Morales, 1999, p. 40).

Although, as justified in The Architectural Space (Muñoz Serra, 2012), the moment we act on the territory, building with artificial elements and/or having other natural ones to shelter us, we are leaving traces on the totality of the spatial or extensive. Thus, the tobacco drying sheds act on the geographical territory, signifying themselves as constructions in which the characteristics of the envelope play a clear role in confining the space, constituting cut-outs of the spatial and contingent reality of the place; they are Fissures of Context that fragment time, thus allowing a perception of a changing but continuous reality (Heidegger, 1927/2012).

5.3. Chronology

In reality, or rather in our perception of reality, the passage of time is what it is: relentless and inevitable. With this invariant, the human being evolves without getting to know any other measure of it, although we can intuit it.

Time is both evolution and mutation. It is the dimension that is still unchangeable (at least as far as our senses can reach) and that never ceases to interact with matter. It has no real reference, as it depends on the perception of each being. What for some is distant for others is recent, what for some may mean a continuous present that continues into the future, for others may mean a forgotten past. Similarly, architectural time can be quite subjective. From the moment that materiality is considered as one of the essential invariants of architecture, the substantiality of architecture is at the mercy of destiny. For architecture in general but for the architecture of the tobacco dryer in particular, time leaves its imprint on the place, it is similarly part of its essential condition and participates in its architecture in very different ways.

According to Heraclitus of Ephesus, the mind organises facts and understands them in an orderly and individualised manner for each subject, allowing the human being to face reality in an orderly way in accordance with the dogmas defined by biological time, which is the one perceived and which interacts with external, natural and ontological time.

The watercourses of time flow metaphorically, depositing matter and memories on the banks. These dejections, ultimately depositories of the events of history in each place, which accumulate on the banks, next to the dry land, form part of the present of the place and of the situation, but they also form part of the river, which flows and maintains the continuity of its course. It is therefore often difficult to discern in an even-handed way what has happened, what is happening or what is to come. To return to the allegory and from another angle of vision, the banks of silt and sand belong to two worlds that inevitably end up excluding each other: the firm, immobile land that ends up silting up and the land that continues to move, dragged by the water, because its place and time to stop has not yet arrived. But there is still a third category of events, which would correspond to those facts and memories that remain for a time, sometimes very intensely, only to continue to be swept away by the current over the years, after leaving a deep mark. This is the group in which all those facts and events related to tobacco culture and the architecture generated for its production and transformation could be included. This gives rise to an architecture that is proportionate to demand, time and place (Guideon, 2009).

Specifically, it is a culture of transfers, bequeathed by the passage of an economic current that half a century later would move on to the region of Extremadura, but not before leaving a very important economic and cultural legacy in the territory of Granada. The arrival of this unique crop in the province is complex and its temporary establishment even more so. The roots are an obvious physical presence, but also of a speculative one, less visible and therefore less known, but equally determining and rich, often objectively valued over the years, when enough time has elapsed to consider its entry into local history objectively.

Time has turned the drying shed into a sturdy symbol; a recognisable architecture of unquestionable historical value that has become greater the more time passes by.

The continuous seasonal cycles cause the aging that is intrinsic to all living beings. The aging of the elements that make up the drying shed makes it necessary to repair construction systems and replace worn or unusable materials, which become the true witnesses to the passage of time. Time intervenes in this case as a creative agent and the envelope of the drying shed as the recipient of its relentless passing.

6. Conclusions

The traditional drying room for curing tobacco is a building with very unique properties. Its interior is ambiguous, allowing one to feel the passage of time and turning the spectator into an actor, making him or her a participant in both its interior and exterior. The skin is so integrated into space and time that it simultaneously separates and unites, effortlessly combining the restricted space (Morales, 1999) with the open space, to the point that one has the sensation that time can break at any moment letting us unconsciously pass through the laws of abstract space and time. On the basis of the references by Aegea and Moratalla (2020), we agree with the statement that the awareness of the impact of the experience of time on architecture (Franck, 2016) has highlighted the significance of inhabiting time (Pallasmaa, 2016), generating a relationship between architecture and history that replaces the traditional claim of building forms capable of remaining unchanged over time with the will to build forms capable of maintaining a constant identity in change.

In the recording carried out under the premises established in the methodology, it is possible to affirm that the concepts of space and time, physically inseparable, can maintain geometry as a nexus of union, an architectural invariant that refers to the place and that is only subject to natural chronology. The triple integrating continuity in the geometric chronotope constitutes the unity in which the physical phenomena and events of the universe occur. Time is implicit in the architectural abstraction of the model and its transience in perception.

The presence of architectural form, and rather the geometry of it, shapes the identity of the place, leaving a patent and a particularly formal imprint on the territory and on the collective memory, observable through the passage of time. In the calendars of life: architecture, place and matter blend together.

In the architecture of the tobacco curing houses, analysed as a paradigm of essence and timelessness, the geometry remains, but the materiality changes. The place remains, but its appearance is different in each season and over the years. As periods of time go by, what surrounds us changes, but at the same time the human consciousness, with its particular perception of the concept of time, observes its flow in any instant activity. That is to say, human consciousness feels the passage of time as a private dimension alien to natural chronology.

Geometry transcends place, materiality and time (Fig. 3) and constitutes the essential property for maintaining architectural integrity and identity both in abstract space and in the particular mind of each human being in his memory and imagination.

This is the case of the enclosures of tobacco drying sheds, whose permeability allows for sensory transparency.

It comes from the Latin geómetra and this in turn from the Greek γεωμετρία from γῆ gē -earth-, and μετρία -measure-.

It results from the prefix τύπος-týpos-, with the meaning of trace or mark, followed by λογία -logia-, the connotation of which is -study- or -science-.

German word that can be translated as spirit of the time, spirit of the moment or spirit of the age.