1. Introduction

Time is undoubtedly a factor of great importance in heritage intervention. It is present in the building’s history as an object that has been constituted and transformed over the years. It is also present in the new intervention as it establishes a new temporal stratum that must dialogue with the monument’s pre-existence.

Furthermore, this new action must be able to relate to the building’s history and its present in order to establish an appropriate dialogue with the monument. To this end, the concept of time can be a valuable resource in defining relationship strategies.

This article explores the concept of time as a resource for establishing an appropriate dialogue between old and new. To this end, the concept of time associated with various parameters in heritage intervention is studied.

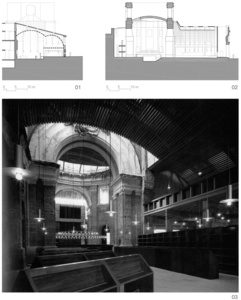

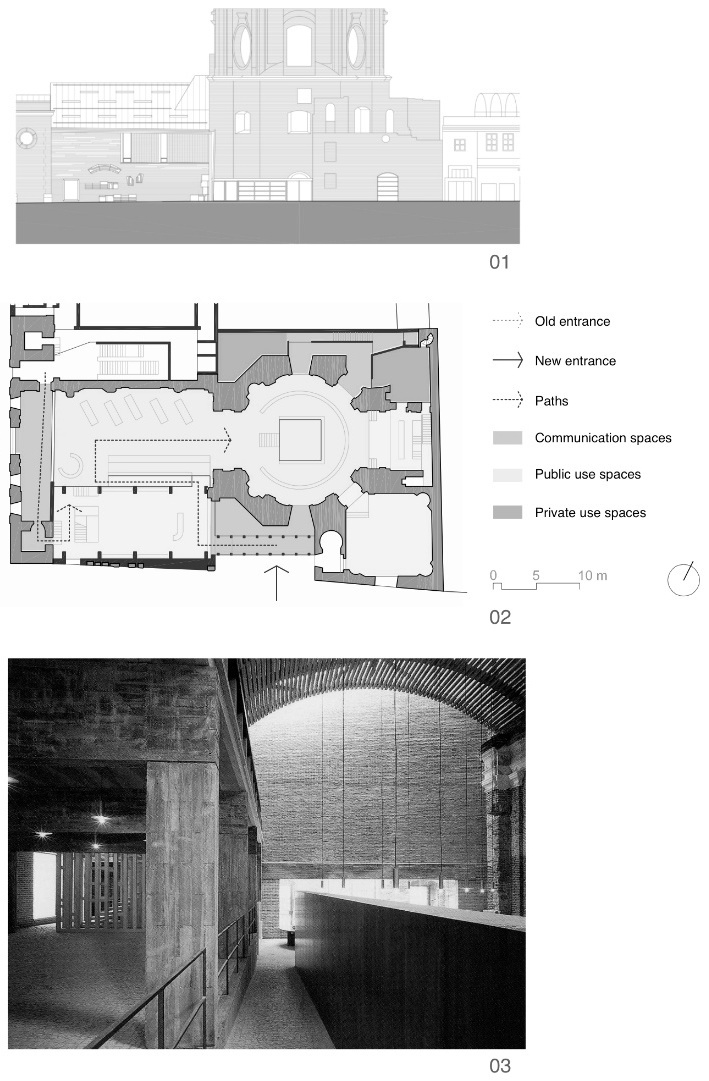

To illustrate these concepts and make them more comprehensible, the theoretical analysis is accompanied by the study of a specific case of heritage intervention. The case analysed is the conversion into a public library of the former church of the Escuelas Pías located in the Lavapiés district of Madrid, carried out by the architect José Ignacio Linazasoro between 1996 and 2004.

2. Time as a resource for interpretation and action on pre-existing architecture

Time and memory

In the interpretation of pre-existing architecture, the first thing that arises is the need to understand the evolution of the building over time and, therefore, to assign to each part a specific historical moment. In this analysis, a more or less complex process of transformation will be observed, which will have involved the introduction of additions and subtractions to the building. The first reflection is that any intervention involves a transformation, which gives rise to both the gain and the loss of values. As happens with memory in human beings, to think it is necessary to select and, therefore, to remember it is necessary to forget so that we can construct a coherent discourse (Boscarino & Cangelosi, 1999, p. 74). This transformation is required to achieve the permanence of the monument in the present. Therefore an “open conservation” must be considered, in which respect and interpretation of the old are accepted on the one hand, and on the other hand, the capacity of the intervention to give it a contemporary use (Spadolini, 1987).

Past, present and future

Heritage intervention must consider three different moments of the monument: its past understood as historical evolution from its initial configuration, its present situation prior to the intervention, and the possibilities of transformation in the future (Franco & Musso, 2021). As Adriano Cornoldi (2005, p. 10) rightly says, any place is at the same time the host of significant pre-existences, a theatre of lost memories, a deserving subject of expectations. These three different times can be associated with three ways of intervening: recovery of values of the past, consolidation of values of the present and creation of new values.

Recovering lost time: looking back at the past

The desire to recover an element of the past may arise from the need to recuperate a referent of a specific cultural moment. This is the idea introduced by Winckelmann in the 18th century, who tries to explain the reason for the beauty of works of art by distinguishing between the original and the added. The antique work is valued for what it is, directing the actions towards the recovery of the work as a witness document of another era (Jokilehto, 1986, p. 7).

According to this idea, a traumatic loss of a very significant monument may require a reconstruction “dov’era e com’era” [where it was and as it was] (Sette, 2001, p. 110) in order to recover its value as a reference of a historical period. The aim is to make the passage of time disappear to a certain extent, filling in what is missing and maintaining the form, materiality and location. Consequently, it is a question of restoring maximum splendour to an element of great artistic value that has deteriorated over time. However, a reconstruction always involves a reinterpretation of what previously existed and, therefore, a creative act. As Cesare Brandi (1963) says, It is a matter of recovering the evocative efficacy of the building and thus its potential unity.

The reconstruction carried out may also be partial, as in the case of anastylosis, a strategy of repositioning building fragments to recreate the architecture of the past. It is a reconstruction with a partial component, which recomposes an idea of scale and volumetry without losing the idea of the fragment. As Stefano Gizzi (2002) states, the partial image of the restored monument is false because it presents a reality different from the original. For example, the city of Palmyra in Syria, where the forest of raised columns is unrealistically transparent, as they were originally outlined on the walls of the surrounding insulae. It is a partial allusion that didactically seeks to exemplify a part that evokes the whole, a suggestion of what was, through a new reality.

On the other hand, looking at the past can also be interpreted as a recovery of certain elements, traces, and rhythms that can partially recover the memory of the building and interact with the new contributions (Casadei, 2022). The traces in the city tell us about past times; recovering the traces and making them visible helps us understand a past story; they leave the mark of time (Caja, 2021). The traces help to establish rhythms, modulations, and systems of order that define the constructions that are overlapped and, in this way, survive in the new interventions. There is thus a sort of temporal transposition of the past.

Time paused: looking at the present

The look at the present, understood as a state degraded by the passage of time, talks about unfinished or partially destroyed architecture. It shows the concept of process, of a dynamic object that is projected from the present into the future, open to new actions. A non finito that conveys the concept of eternal becoming. Thus, losses can produce new plastic possibilities in buildings; they allow the configuration of new balances.

It recalls the vision of John Ruskin about the picturesque, which he defines as “parasitical sublimity” that can be understood as the beauty of imperfection. The picturesque is present in ruin and decay, in the sublimity of the rents, fractures and stains, “it is an exponent of age, of that in which the greatest glory of the building consists”. For Ruskin those external signs are essential characters of the building to the extent of ensuring that restoration is “the most total destruction which a building can suffer”. And he adds, “there was yet in the old some life, some mysterious suggestion of what it had been, and of what it had lost; some sweetness in the gentle lines which rain and sun had wrought” (Ruskin, 1925, pp. 351–354).

It can be interesting for the project to capture this instant, to fix it in order to perpetuate its image in time. In this sense, Michelangelo’s work of transforming the Baths of Diocletian into a church is a powerful example. Michelangelo conceived the project as a minimal intervention consisting of a slight modification of the interior, maintaining the image of ruin on the outside, giving the image of incomplete work. For Vasari, 86-year-old Michelangelo was deeply concerned about death and the salvation of the soul, something he conveyed with great expressiveness in his last sculpture, the Pietà in Rondaniemi, in which he renounced the idealisation of reality and opted for a more spiritual language (Jokilehto, 1986). Michelangelo admires the beauty of ruin, even dispensing with the need for ornament.

This idea links up with the concept of timeless architecture. The loss of ornamentation due to the degradation of materials over time generates a simplification of form as only the essential structures that define it remain in architecture. In the same way, the layers of cladding that define the finishes deteriorate over time and are lost, bringing the material of the load-bearing construction systems to the surface. The result is an architecture that shows no signs of any particular style that would make it identifiable with a specific historical moment, giving it a certain degree of timelessness.

In the same way, new architectures can be defined by these criteria of material simplification and formal abstraction in order to relate to pre-existing buildings and denote this idea of temporal indefiniteness. This approach involves the idea of temporal continuity. Sometimes, the intention may be to merge the new performance with the pre-existing one, seeking temporal continuity between the two parts. The unity of the whole is prioritised over the idea of temporal overlap. However, the new addition can sometimes be recognised through specific design mechanisms that make it identifiable to the most attentive observer. This idea is clearly present in Souto de Moura’s intervention on the monastery of Santa Maria do Bouro, in which he completes and extends the pre-existence by using the stones of its ruins.

Temporal accumulation: looking to the future

Transformation over time produces the accumulation of layers, constructions that are superimposed to meet needs. It can be an exciting resource regarding the contribution of new elements, making these additions evident to show this desire for evolution, the sum of moments from different periods. Additions, employing complex games of analogies and contrasts, seek to generate a coherent whole. In this sense, these additions may seek a certain temporal continuity with one of the existing strata or stand out emphatically to signify their novelty.

The relative position of additions also plays a fundamental role in their relationship with pre-existence. The enveloping architectures protect the remains, adapt them to the new urban needs, and conceal them to a certain extent. Interior architectures respect the temporal perception of pre-existing architectures from the outside but transform their interior spatial conditions. Finally, overlapping architectures seek to blend with each other to achieve greater integration.

In this sense, it is worth distinguishing two concepts that relate to two ways of interacting with the pre-existence: the part and the fragment. Massimo Cacciari (2000, as cited in Cavalleri, 2008) clarifies the difference by indicating that while the part is subordinate to a whole, so that there is an irrevocable relationship between them, the fragment is a piece of something that can acquire multiple interpretations. Thus a variable with an obvious influence is the dimension of the parts, the pre-existing part versus the new addition. Similar dimensions give rise to a balancing act, with both parts having similar importance in relation to the whole.

A concept derived from this idea is that of simulations in time present in the works of Carlo Scarpa and Giancarlo De Carlo, who seek to simulate the temporal layering of different construction phases over time, making the expression of these construction phases part of the formal meaning of their works (Purini, 2006, as cited in Carbonara, 2011). A clear example is Scarpa’s intervention in Castelvecchio, where he breaks down the pre-existing architecture into its component layers to explain the construction as a superimposition of layers built up over time, and onto which he incorporates new, clearly identified layers.

3. Case study: conversion of the church of the Escuelas Pías into a library

In this work, the architect José Ignacio Linazasoro manages to generate an architecture of great interest by employing various resources in which time is shown as a fundamental concept. We will now attempt to unravel the reasoning behind the tools employed.

The Incomplete Order. The sum of fragments from different times

For Linazasoro (2003, p. 84), architecture is essentially the expression of incomplete Order. While in the past, architecture was the expression of Order capable of explaining the centrality of man in the Cosmos and his relationship with the Sacred, today, however, following a process of secularisation, there is a decentralisation that prevents it from being formulated in the certainty of this complete Order. But since this Order is the foundation of architectural identity, it must be achieved through articulating various partial discourses, the sum of which can evoke the totality.

Therefore, the loss of the canonical Order implies not understanding architecture as something ideal and isolated but understanding it as part of a palimpsest, a sum of fragments where the new is added to what has already been built to form a whole (Presi, 2012, p. 26).

Strategies for relating the fragments of the Incomplete Order

Since architecture is therefore understood as a non finito composed of fragments, concepts that make it possible to link some elements with others to create a new whole become particularly important.

In the intervention on the pre-existences, Linazasoro does not seek to reproduce the original architecture, as he understands that this would be anachronistic, but neither does he seek to contrast the remains with an openly modern architecture, as this would be banal. He, therefore, opted to direct the new interventions towards transforming the original building to adapt it to the new functional needs and the new demands of the relationship with the place.

In the Escuelas Pías, the pre-existence, far from having a destiny marked by its origin, is shown as an expression of multiple suggestions for its adaptation to a new reality that is different and distant from the initial reality. Thus, Linazasoro interprets the changes in the relationship between the building and the public space and adapts the pre-existence to new accesses and paths. In doing so, he modifies the reading of the original building, constituting a new spatial sequence and relativising the value of an axial route, which has now disappeared and is meaningless.

In this line of manipulation of the pre-existence also arises the idea of imagining a fictitious past of the place and constructing the buildings on this fiction. Therefore, the past is understood as the memory incorporated into the present and projected into the future, a mouldable past on which to act, what Antonio Machado calls the “apocryphal past” (Machado, 1957 as cited in Linazasoro, 2003, p. 99). In such a way that by intervening in a building, Linazasoro seeks to appropriate it and its past and to rewrite it. The past is “fictitious” in that it is a reinterpretation, a reworking of reality by the subject, which draws on other realities.

This reinterpretation seeks to use references that evoke a totality. It is a matter of understanding architecture as a “virtuality of construction” present, for example, in the capacity of the ruin to evoke the disappeared covered space (Linazasoro, 2003, p. 101), in such a way that the incomplete Order of the fragments that constitute the work is mentally completed through reference to a model.

Thus, Linazasoro’s works draw on references taken from architecture throughout history, both classical and modern. However, these references are not chosen randomly but follow what Focillon calls the “famille spirituelle”, i.e., families of architects who learn from each other due to a common interest in things, an interest in the same idea of architecture (Focillon, 1934 as cited in Linazasoro, 2003, p. 81).

In the Escuelas Pías, various “correspondences” can be identified with past architectures: for example, the ruin of the transept relates it to the Minerva Medica. Each of these elements acquires a charge of intensity based on personal references or experiences, relating some fragments to others through memory and, in any case, avoiding reconstructing a reality that may have existed in the past (Baudelaire, 1857 as cited in Bosch Roig, 2013, pp. 271, 465).

Linazasoro understands that creating a transitional space between the interior and exterior is necessary to resolve the relationship between parts of an incomplete context. With this continuity between inside and outside, the idea of the non finito is strengthened, where the limit of the building is not in itself but in the city (Presi, 2012).

On the other hand, the new conception of time derived from the incomplete Order introduces perception in sequence instead of static perception, producing an understanding of the totality through the sequential reading of the different fragments that constitute it (Presi, 2007).

In the Escuelas Pías, Linazasoro produces a transitional path between exterior and interior that allows one to escape from the cyclical time of the present and enter a timeless world. Both realities are naturally linked through a succession of spaces of progressively increasing heights and ramps that lengthen movement and materials of an exterior nature.

On the other hand, the new lighting of the space seeks to maintain the uncovered and incomplete atmosphere inherited from its period as a ruin utilising small, scattered skylights on the roof, which emit light filtered through the openwork vaults. The vaults are cut away to allow more light to enter, thus reinforcing the reading of the wall fragments, helping to break up the space and add drama to the environment. Flashes of artificial light create contrasts that enhance the atmosphere of half-light.

Another strategy Linazasoro employs in his projects is a composition based on the relationship between opposing concepts. Adriano Cornoldi comments on the balance Linazasoro achieves in his work through the dialectic between the grid and the arch: the first gives the order, the second identity. “The grid relaxes, the arch polarises: together they synthesise architecture” (Presi, 2007, p. 239).

In this line, Linazasoro understands that in his work, there is a continuous reflection on the superimposition of strata in a way that two situations are produced: on the one hand, a tectonic relationship of an element supported as in a classical linear structure; and on the other hand, an illusionist relationship of suspension of an element in the air, such as a velarium or a Byzantine vault. In such a way that he tries to make the two systems compatible in his projects according to need.

In the Escuelas Pías, the tectonic sense can be seen in the construction of the mezzanines. The new concrete porticoes and wooden structures recall an elementary game of constructive superimposition of linear elements, which has a sense of temporal accumulation, where in the first place would be the support, originally made of wood, which gradually solidifies over time to become a stony material, recalled through the traces of wood in the concrete. Weightlessness can be appreciated in the construction of the dome, which is conceived as a sizeable shady shelter whose materiality seeks to create an atmosphere of mysticism and whose shape suggests natural protection from the weather (2013, p. 466).

On the other hand, Linazasoro uses the concept of temporal superimposition, understood as the result of a process in which the original pure architecture becomes contaminated through the accumulation of layers over time, in such a way that the architecture is enriched thanks to the contribution of these impurities.

In the Escuelas Pías, the new elements are integrated with the pre-existing elements, adopting a provisional or permanent character depending on their role in defining the space. The building comprises three different levels of superimposed strata: firstly, there are the brick walls, which constitute a stratum of an immutable time; secondly, there are the structures built with new materials such as concrete and wood, which constitute a stratum of a current and active time; and finally, the ephemeral temporality of the furniture and the user, whose forms and positions can vary without influencing the other levels (Presi, 2012).

Linazasoro understands that the relationship between the fragments can be satisfied by reflecting on the theme of Alberti’s concinnitas, understood as an interpretation of modernity within the tradition. For Linazasoro this harmony is achieved through the assumption of permanence, of the textured, of the correct scale and not so much through the light, the smooth or the monumental. It is about creating a habitable atmosphere rather than a sum of autonomous objects (Presi, 2012, p. 20).

For the architect, reflection on the materials and techniques with which pre-existences have been built is one of the ways to achieve a positive response to the “tension between nostalgia for the past and the need to break with it” (Linazasoro, 2003, p. 100). In this sense, Linazasoro understands that the passage of time marked on the surfaces of monuments, through patinas and fractures, should be preserved, as these “defects” make the image of the buildings more pleasant.

In the Escuelas Pías, the materiality of the new elements is approached from the essentiality of their construction, being shown without cladding, as a reflection of the expressiveness of the ruins on which they stand. Each new element acquires a different material in response to its constructional function: brick for the walls, grey reinforced concrete and dark grey painted wood for the load-bearing linear structures, light wood for the floors and ceilings, dark wood for the joinery and furniture, stone for the flooring, and zinc sheeting for the roofs and water drainage.

4. Conclusions

Throughout the text, it has been highlighted how past, present and future constitute three moments of any intervention in heritage. The past time provides us with the initial compositional logic; the present time reveals its successive transformations; and the future time proposes a new life adapted to current needs. Each one contributes specific values to the configuration of the whole, but the difficulty lies in defining a discourse that provides unity.

Through the analysis of the work of the Escuelas Pías, we have seen how Linazasoro makes use of a universe of tools that allow him to link the fragments of the different periods of the monument. Materials similar and different to the pre-existing ones, as well as allusions and references to the past and modernity, respond to a play of background and form articulated by the paths connecting the different parts of the intervention. A relationship is thus produced through similarities and differences, analogies and contrasts that make up an incomplete architecture, with the spectator left to re-establish Order.

In the end, it is a question of interpreting the remains as material to be used in the project, seeking to configure a work whose objectives have to do with questions inherent to architecture, where the relationship with the place, materiality, space and light are the variables that act in the Architecture.