1. Introduction

“Do you know what you are? You are a manuscript oƒ a divine letter. You are a mirror reflecting a noble face. This universe is not outside of you. Look inside yourself; everything that you want, you are already that.”

~ Rumi ~

Time and space are inextricably linked. They complement one another and give each other meaning. They are also both fundamental aspects of architecture. The three dimensions of width, length, and depth are found in space, while the fourth dimension is time. It is through time that space becomes activated, while they both encompass the physical world as we see and perceive it. Architecture is encountered and its meanings are understood through one’s full presence in space, even though the experience is not perpetual. To access the transcendental aspects of the internal world made evident through the external, the idea of temporality offers a valuable description of how we perceive both dimensions in a more concrete way.

Temporality is both important in architecture and in Sufism - the mystical dimension of Islam. This study was performed to explore the concept of temporality and time in Persian architecture through the lenses of sacrality and Sufism. The goal is to connect the idea of the external (Zahir) world with the internal (batin) and explore the importance of the physical world for understanding and grasping the metaphysical. In other words, the seeker (Salik سالک) must pass through the transitory physical world as a way, or Shari’at, to arrive at the truth, or Haghighat. In the introduction of the book “Sense of Unity”, Dr. Hossein Nasr also highlights: “There is nothing timelier today than that truth, which is timeless, than the message that comes from tradition and is relevant now because it has always been relevant. Such a message belongs to a now which has been, is, and will ever be present” (Ardalan & Bakhtiar, 1973, p. xi). In Sufism, students learn to understand that they are one with everything in the universe, even the cosmos. This is a similar concept in architecture, where all the elements come together to create a moment and convey a message as a whole. The work of architecture should be viewed as a totality rather than as the sum of its components—gestalt (Sinclair, 2000).

To date, only a limited number of researchers have discussed and explored the notion and relationship of time and temporality in sacred architecture, specifically through the lens of Sufism. This research is different as it focuses on bringing an ontological concept of temporality and connecting it with the physical world of architecture. In the pages that follow, it will be argued that temporality is important both in the spiritual aspect of our life as well as our physical experience of architecture in connecting us with the essence of self. To achieve the ultimate truth (haghighat حقیقت on the Sufi path, the seeker must transition from the temporal (mortal) to the atemporal (immortal). This paper attempts to demonstrate a similar notion in architecture where the spirit and essence of the place can only be grasped by looking beyond the walls and the floor, the brick and mortar. By employing phenomenological modes of inquiry, this paper attempts to illuminate the concept of temporality and time in architecture, through hermeneutics and examines the importance of light and shadow in the architecture of sacred spaces. By employing phenomenological modes of inquiry, this paper attempts to illuminate the concept of temporality and time, in architecture through hermeneutics and examines the importance of light and shadow in the architecture of sacred spaces.

This effort will provoke a new lens for making places that are not just objects but moments, where people may feel and be fully present. This research will contribute to a deeper understanding of the metaphysical and atemporal aspects of architecture in creating spaces that are beyond form and matter. By embedding and coding spaces into a specific mode of experience and character, we can add depth to architecture and create transcendental environments. This paper begins by defining sacred space as well as introducing Sufism and its interpretation of time and temporality in connection to architecture. It will then go on to explain why and how temporality and time are manifested in Persian architecture from the mystical point of view, with a focus on light and shadow, to create environments and spaces that promote a sense of balance and unity between the self and the external world.

2. Transcendental architecture

Buildings are designed to have different purposes. Depending on the purpose of the structure and the program, some buildings are exclusively designed to serve as shelters. The second category includes places that are not only functional but also designed to provide a more human-centered experience and participate in the health and well-being of the occupants, from feeling charged and uplifted to peaceful and healthy. Historically, sacred places have been among the second category, where, through inducing a sense of mystery, timelessness, and wonder, they have attempted to bring man closer to the Divine on earth. Sacredness is defined by Pallasmaa as “a feeling of transcendence beyond the conditions of the commonplace and the normality of meanings” (Pallasmaa, 2015, p. 19). Pallasmaa continues by elaborating on the nature of our connection with the sacred space, where all the “physical characteristics turn into metaphysically charged feelings of transcendental reality and spiritual meanings” (2015, p. 19). Despite the widespread misconception that sacred spaces are all places of worship, they need not be affiliated with any religion. A sacred space can be a garden, a mosque, or even a library. As Paul Goldberger explains, sacred space can be defined as “the use of material forms to evoke feelings that go beyond the material and which cannot be measured” (2010).

Most people believe that architecture is a type of outward and material art that uses space to define human existence and activity (Pallasmaa, 2016). To better illuminate the existential characteristics of space, Norberg-Schulz introduces the idea of Genius Loci, or “Spirit of place” in architecture. This is a quality that can facilitate the creation of meaningful spaces and poetic atmospheres beyond the physical dimension. He explains that the interaction of people with places is based on their disposition and recognition of the space - one can dwell when he can “orient” within and “identify” himself with the environment he is placed in (1980). We are interconnected with our surroundings, and our relationship with our environment affects how we see and comprehend space. Through the concept of ‘self in place’ or ‘self-transcendence’ (Birch, 2014). As Chang states, the sense of place is the result of a “fuller engagement of the self in place.” This is due to the fact that “the development of the self moves from individualistic concerns to harmony with other beings as it grows in wholeness (i.e., maturity, spirituality)” (2015, p. 140). She then defines “self” as “the coherent whole” or the "unified consciousness and the unconscious being of a person (Chang 2015, p. 140).

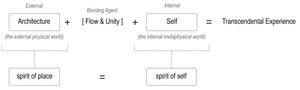

Spaces with mystical qualities aim to act as a conduit, linking us and cultivating our connection with what otherwise would be inaccessible—the Divine. The one that "has neither beginning nor end, for it is timeless, and there is no place for him to be known by location or attributes. Professor Nader Angha states, “All manifestations are the single melody of his symphony” (1996, p. 23). Only by merging the physical world with the metaphysical and flowing from one to the other, outside of the boundaries of time and space, can one achieve transcendental experience—the realm of Divinity that is filled with serenity and tranquillity (Esmaeili & Sinclair, 2021). Refer to Figure 1.

The feeling of flow, which is linked to the concepts of temporality and time, is a crucial aspect of space. Flow occurs when we are completely immersed in the experience of the present moment and fused with its temporal and spatial dimensions (Csikszentmihalyi, 1996). Spaces start to blend together when we enter a built environment, and we go seamlessly from one experience to the next, sometimes without even realising it. As Pallasma asserts, we occupy time, but it is important to understand that time occupies us too (2016). The concepts of time and space are interconnected in architecture. We comprehend time using our human senses rather than how physics describes it. We not only inhabit space and time, but we dwell in both simultaneously. To understand the concept of time, architecture plays an important role as it “mediates equally our relationship with this mysterious dimension, giving it its human measure” (Pallasmaa, 2016).

Through the minds of phenomenology, spatial phenomena, such as atmospheres, are fundamental to the perception of architecture because they are continually “intertwined with temporality” and are “never outside time” (Pérez-Gómez, 2016). It is through the experiential aspects of architecture that we connect with space. Time and space are inextricably linked to the limited physical world, which lacks stability and is always changing. Professor Sadegh Angha talks about how time and space are related by stating that “Without space, time will not exist. Till there is no space, time will not be existent, though it will be limited only” (S. Angha, 1998, p. 242). Although time and space are both required and vital for experiencing the metaphysical world, one should look further to find the essence of architecture – the Spirit of Place. Temporal and ephemeral encounters play a significant role in the design of sacred spaces because they serve as a reminder of the finite, ephemeral nature of this world in contrast to the eternal one we should be seeking.

3. Sufism and time

"Pass the limit of time and space

Then in God’s realm, you will attain (the station) self-less-ness

One must become the ‘inner essence of the soul’

Do not seek the soul in ordinary time/ space coordinates

Do not seek the soul through physical (bodily) demonstration

Don’t permit your own imaginary perceptions takeover" (S. Angha, 1998, p. 240)

Sufism, or Tassawof (تصوف) is defined as the internal (batin) and esoteric dimension of Islam - a self-discovery journey towards oneness and unity with the Divine. Being a mystical course is what makes Sufism unique and sets it apart from the religious and exoteric (zahir) facets of Islam. Mysticism refers to “the great spiritual current which goes through all religions. In its widest sense, it may be defined as the consciousness of the One Reality – be it called wisdom, light, love, or nothing” (Schimmel, 1975, p. 4). Another distinguishing element of Sufism is the esoteric transmission of knowledge from one master to another, and this is why Sufism is called the path of the heart (Burckhardt, 2008). In the journey of self-cognition, the Sufi (seeker of knowledge and wisdom) should pass through three stages. They are: the Tradition or laws (shari’at شریعت), the Path or the Way (Tarighat طریقت), and the Truth (haghighat حقیقت). To better understand these stages, professor Sadegh Angha explains: “shari’at is like the ship, tarighat like the sea, and haghighat like the treasure; therefore, whoever desires the treasure must embark, sail the sea, and reach the treasure” (1986, p. 5). The physical world is limited and confined by the dimension of time. However, to discover the truth, one must first enter the physical world and utilize it as a springboard to transition from the external to the internal. The physical world “teaches us that it is possible to emerge from measurable space without emerging from the extent and that we must abandon homogeneous chronological time to enter that qualitative time which is the history of the soul” (Corbin, 1982, p. xxvi).

On this journey, the seeker aims to separate from all the physical attachments and distractions of the ego to arrive safely at the destination and reach the truth within one’s heart. Sufism places a lot of emphasis on the heart as the center of “mystic physiology” (Corbin, 1969). As a result, the Sufi seeks to become physically and cognitively aware of the heart by practicing Sufi principles such as chanting (zikr), prayer (salat), or concentration (tamarkoz) both internally and in Sufi centers (Khanegah). Figure 2 displays images of two Sufi centers in the USA. Khanegah translates to ‘house of present’. It is the school where the student (Salik سالک) turns for guidance. The word khane means ‘house’ and gah means ‘present moment’. It is critical for the seeker to gradually learn to detach himself from the past and the future to be fully present in the Now (hal), which is also one of the infinite attributes of the Divine - always present. This moment is defined elegantly by Gerhard Böwering as “the breath between two breaths, the one before and after, that cannot be overtaken again once it is gone” (1992, p. 83). The constant heartbeat along with the continuous act of inhalation and exhalation (circular motion) are tangible and temporal aspects of the physical body that are taking place in the present moment. They function as a means of returning the Sufi to the present moment. Bringing one’s complete consciousness and attention to the timeless and limitless moment of ‘Now’ will result in silencing the chattering mind that is constantly traveling in the past or future. Thus, creating a gateway into the peaceful realm of the heart to encounter the self.

To become aware of the moment and unify both the external and internal worlds, the Sufi is practices solitude, stillness and silence. The external and physical practice of being calm, in balance, and quiet allows the Sufi to enter the serene realm of within. One becomes unified with nature and the cosmos once all the barriers of time and space are lifted to reach the ultimate truth that is timeless (bi zaman بیزمان) and spaceless (bi makan بیمکان). The seeker’s task is to abandon any “trace of temporal consciousness” and become fully present at the moment within his heart to reach his eternal self (Day, 2004). A Sufi who is fully aware and immersed in the present moment is also called " Ibn waqt ابن الوقت" which translates to “son of his moment” (Böwering, 1992, p. 83). As previously explained, time is the fourth dimension, which is intertwined with space. In Sufism, the fifth dimension is called life or “Jaan جان”. This dimension is the eternal source of life, wisdom, and knowledge, within the heart but outside space and time - a pure reflection of the Divine. To explain the celestial qualities of “Jaan”, Professor Sadegh Angha states: “The fifth dimension is the expansion of your soul, which is delicate and knowledgeable from inception” (1998, p. 235).

4. Presence in architecture: Here and now

It is essential to highlight that in Persian architecture, man is ‘present’ in space rather than ‘using’ it (the user), and his ‘being’ in space is what matters most- full presence (Haeri, 2015). Historically, man, through sacred art and architecture, decelerated time to become present, here and now, to access and experience the invisible. We are attracted to beauty, harmony, order, and creativity. When confronted with an astonishing and staggering sense of beauty and majestic qualities, our full attention is captured by the moment, resulting in an “experiential epiphany” or “transcendental quality,” triggering something internally and bringing us closer to the source of life within (Sinclair, 2011). According to renowned architectural phenomenologist, Alberto Perez Gomez, we can identify architecture as a “poetic language” (2018). A form of art that moves us beyond form and matter and “enable[s] humanity to overcome its immediate presence and experience a time out of time that is free from both linear temporality and the dreaded return of the same” (Pérez-Gómez, 2018, p. 192).

Architecture has always been a powerful medium that allows one to simultaneously perceive space and time. Our ability to reflect, empathize, and identify with others is something that design can accomplish. We internalize space and the atmosphere as soon as we enter them, whether we are aware of it or not (Pallasmaa, 2021). As with sacred spaces, this internalization of space allows one to be present within it and to completely immerse in the here and now (hal). A feature of sacred architecture that brings us closer to spirituality and the present moment is space and the temporality of man’s sense of space. Full consciousness and awareness of the present moment “while it can be conceptualized by science (and our clocks) as a quasi-nonexistent point between past and future, is experienced as thick and endowed with dimensions—in a sense, eternal. This has always been the time ‘out of time’ that is the gift of rituals, festivals, and art, or the time of ‘silence,’ celebrated by Louis Kahn and Juhani Pallasmaa for architecture” (Pérez-Gómez, 2016, p. 257). Art in general, whether it be architecture, music, painting, or poetry, permits us to suspend time and offers the chance to encounter something immeasurable outside the limited dimension of time (Pallasmaa, 2016). By declaration of time, one is forced to become present at the moment to enter the realm of atemporal unified internally and externally, where time and space disappear. By implementing various design elements in the work of architecture, the designer can create a journey through light, material, form, and choreography of the space where one not only blends with the dimension of time but can reach the fifth dimension - “Jaan.”

5. Temporality in Persian architecture – Light and Shadow

“Darkness is absence of light. Shadow is diminution of light.” ~ Leonardo Da Vinci~

Temporal spaces and moments in architecture are of high value to our understanding of the present moment. We can characterize the passage of time and understand atemporal through the ephemeral nature of space. Understanding the significance of the transient qualities in architecture is thought-provoking and reminds us that the “eternal archetypes of spiritual and celestial qualities are reflected through temporal forms, manifesting vital, yet mortal, tendencies which are crystallized into transient styles representing physical and individual limitations. Secular forms, therefore, serve as a bridge between the qualitative, abstract world of the imagination and the quantitative artifacts of man” (Ardalan & Bakhtiar, 1973, p. 97). We consider time and anything beyond the physical through the oscillations we observe in the physical world, such as seasonal changes, natural growth, sun/moon motion, and day-night cycles. In Sufism, it is the light within one’s heart that symbolizes the eternal Divine - the source of all existence and the guiding light for the seeker on the path of self-cognition.

Historically, light has been one of the key elements in sacred architecture. In many faiths and cultures, light is associated with sacrality (Esmaeili & Sinclair, 2021). It is known as an emblem of purity, life, and knowledge and is associated with heavenly representations both in art and architecture. As defined by Mario Botta, light is “the visual sign of the relationship that exists between the architectural work and the cosmic values of the surroundings” (Cappellato, 2005). Light symbolizes absolute reality and knowledge, while darkness is the state of nothingness or ignorance. Ardalan defines light in the mystical context as an “absolute existence while darkness is analogous to the phenomenal world” (1974, p. 166). In full darkness (a state of nothingness), we are unaware of our surroundings. However, in the presence of light, we can gather information and move through space. In describing the interconnectedness of light and shadow, Al-Ghazali states, “Know that the visible world is to the world invisible as the husk is to the kernel; as the form or body to the spirit; and darkness to light” (Smith, 1944).

Light defines the atmosphere and the depth of space. Louis Kahn refers to light as the “giver of all presences” (Kahn, 1991). The ephemeral quality of space and atmosphere becomes accentuated through the movement of light, resulting in a more dynamic and animated space. Light also “directs our movements and attention, creating hierarchies and points of foci” (Pallasmaa, 2015, p. 24). As a result, light is highly valued in Persian architecture and is one of the major factors in defining a space. Light and shadow coexist together, and they are inseparable. The Divine Light is formless, timeless, and eternal. Light encompasses everything in the universe and the cosmos and “matter is nothing but light” as explained by Professor Angha (1981). Louis Kahn calls material “Spent Light,” and he further explains the relationship of shadow to light as " What is made by light casts a shadow, and the shadow belongs to light" (1991, p. 248). If we claim that light symbolizes the atemporal metaphysical qualities of the world, then darkness and shadow represent the temporal and perishable world of matter. The concept of light and shadow is applied to numerous sacred spaces as well as Persian architecture to emphasize the beauty and spiritual qualities of the Divine in comparison to the transient and limited world of the physical.

The presence of light is enhanced in Persian architecture and in the design of the Khanegah by employing the dome and large windows. The movement of light on the trees; various shades of color in flowers as one walks through the Persian garden; viewing the reflection of light on the surface of the water fountain creating magnificent sparkles in the courtyard; the reflection of light on the tiles and details of the center; and the beautiful scenery created by colorful stained glasses inside the building; the movement of light and colors on the floor; the interplay of light and shadow in different corners of the room, as well as stepping to the center of the space underneath the dome where one is showered with light, all share one quality, and that is the temporality of space and the quality of light (Figure 4). Our spatial encounter of space represents exquisiteness and beauty, but temporal aspects of the physical world that are constantly changing (Ardalan & Bakhtiar, 1973). However, it is through the physical manifestation of space that we move past the experience of architecture as a product or physical creation. Architecture, despite its permanence, becomes an experiential moment of ‘being’ where one can encounter mystical qualities of the external that will enhance the sense of curiosity and unify one with the everlasting and infinite inner world. As a result, the external (zahir) and the internal (batin) will become unified to create a mystical moment where balance, harmony, and peace dwell.

6. Discussion and conclusion

“A building’s role is to keep us dry, while Architecture’s purpose is to move us.” ~Le Corbusier~

Architecture is more than simply assembling materials and constructing a structure for people to live in. Creating sensory experiences that connect individuals to their sense of self and the environment is at the heart of architecture. Integrating the temporal and atemporal components of space is essential in creating timeless architecture. At that point, one’s internal feeling of self and desire to blend with their environment are further enhanced by the exterior experience of architecture. The goal of the current study was to highlight the significance of temporality in Persian architecture through the lens of mysticism. Architects and designers can bring depth and meaning to the creation of spaces, by examining and understanding the philosophical and theological notions of Persian architecture, teachings of Sufism, and fusing them with the work of architecture. By orchestrating design elements and deliberately focusing on the concept of harmony and self in place, it is possible to inject experiential and transcendental qualities into space that can be felt with the heart and beyond the confinement of time. The scope of this study is limited to exploring one of the many design elements—light and shadow—which have an influence on how space is created in line with the concept of time. To have a deeper and more thorough grasp of the idea of temporality, especially in a rich style such as Persian architecture, it is important to investigate a variety of other factors, among which light and shadow are just two. Additional research will be required to examine and explore transient qualities in Persian architecture in more depth and their connection with all other elements of design. A natural progression of this work is to explore specific case studies and various design elements to understand the application of these concepts in built projects.

_shahmaghsoudi_school_of_sufism_centers.jpg)

_shahmaghsoudi_school_of_sufism_centers.jpg)