1. Introduction

This discussion, carried out in the research titled “The project as research, research as project,” considers not only architecture as the intimate representation of society but also our creative and technical knowledge: architecture communicates and teaches about 1) the social and artistic relations of a community and 2) how the human being relates to the world and transforms his reality. In this sense, this document considers that the being of architecture cannot be determined only as an object of aesthetic appearance, because in the first instance the architecture must offer a solution to the demand for utility; on the other hand, it must respond to a physical environment characterized by certain natural and human pre-existences, to which it adds its own symbolic value. In this way, doing architecture is a political act, in addition to being aesthetic and cultural

This intentionality establishes sensitive configurations projected empathically, where aesthetic fragility should not be confused with weakness or even with vulnerability, it is not a disadvantage for architecture, it is the ontological dimension that emerges from the political sense and that assumes the self-sufficiency and autonomy of the human condition, beyond the precariousness of the context in which it is inserted. This is the starting point of an ethical knowledge that refers to the reflective attitude of the individual and to the discernment about the limits or potentialities that architecture has to know how to integrate in a coherent way with the place to promote social inclusion in empowerment processes.

However, ignoring that architecture is a political act is incongruous, since the decision processes to carry it out involve a dialogue between ethical and aesthetic values, in addition to taking into account the local culture, the specific opportunities of the site and the challenges of caring for the environment, ignoring this would lead to losing the innovative and socially conscious approach to architecture. Then the aesthetic fragility is the ability to integrate the knowledge of the inhabitants of a place in the construction of essential infrastructure of social integration, fundamental to solve the desires, needs and emotions of the communities that remain embodied in the poetic space of the construction by rescuing appropriate techniques from local traditional materials, which transcend time.

Thus, human experiences, generated from social behaviors and triggered by political (but above all ethical) issues are the process by which architecture is evidenced; This is the result of human thought. In fact and according to, Sudjic (2006) “on the other hand, architecture is a subject fraught with real conflicts, […] ranging from the intensely personal to the vaguely political.” This refers to the dilemmas and tensions in relation to the buildings designed and built by the architects, where the least visible conflicts involved in creation are ignored, which leads to the formulation of atypical spaces in radically different forms of production, of social organization and political power; which incites the rupture between the community being and the individual being.

Indeed, this external involvement of power systems in architecture makes it more visible due to the growing economic and media value, which use architecture as an instrument that provides its own representation, constantly ideologized: power uses architecture to establish it as iconic culture and consumer art.

Likewise, Montaner and Muxí (2017); Mostafavi (2017) express that architecture shapes everyday life in a broader sense of being itself, it is based on social signaling that turns the physical and material into a connotation of space, as a subtraction of qualified images based on ethical and political orders of the economic system. In other words, although it is possible a non-alienated dialectic between ethics and politics is possible in the effort of individuals to understand this union of association with each other, the search for relationships cannot start without previous experience and its possible contradictions.

In the same way, Harvey (2014) states that changing contradictions provide the evolution of capital and capitalism as a possibility for new architectures and alternative constructions. This is to differentiate the relationship that architecture maintains with the power from which it sustains with politics. On the one hand, power becomes visible with architecture, through a certain symbolic language that exalts political, religious or economic premises, in which precise alterations of scale, materiality and/or spatiality intervene. On the other hand, the relationship of architecture with politics rests in a structure in which architectural and political contents are made imperceptible. To be political, architecture must be part of public life and catalyst for political actions. A building of this nature must have the capacity to recreate social structures and enhance them, by transforming spatiality in terms of well-being, appropriation, encounter and participation.

So considering the descriptive hermeneutic methodology, an analytical tour is made in conjunction with various writings and architectural projects, which through positions and proposals, have originated political and social actions that promote changes in the face of the need for a sustainable world, societies with less inequalities and better development possibilities. However, this methodology allowed to find connections, ideas and arguments that are addressed in an expository way in three sections and that examine the aesthetic fragility between architecture and politics. In the first, emphasis is placed on the aspects of the representation of the architectural object, where the transposition of the moral law to the domain of aesthetics is given. In the second, architecture is used as a device to conceptualize and think about contemporary conditions at the intersection between aesthetics and politics. And finally in the third section, affinities are established between the action of thought and the processes of architecture.

In summary from this fragile dimension, the arguments will demonstrate that contemporary works become conceptual antagonisms from different senses (aesthetic and ethical), showing that architecture provokes sensations, effects, and affections, and is from the construction of possibilities and of situations that this can deploy all its political potential.

2. Methodology

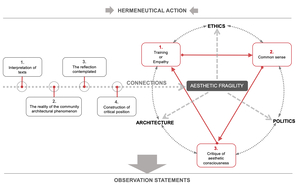

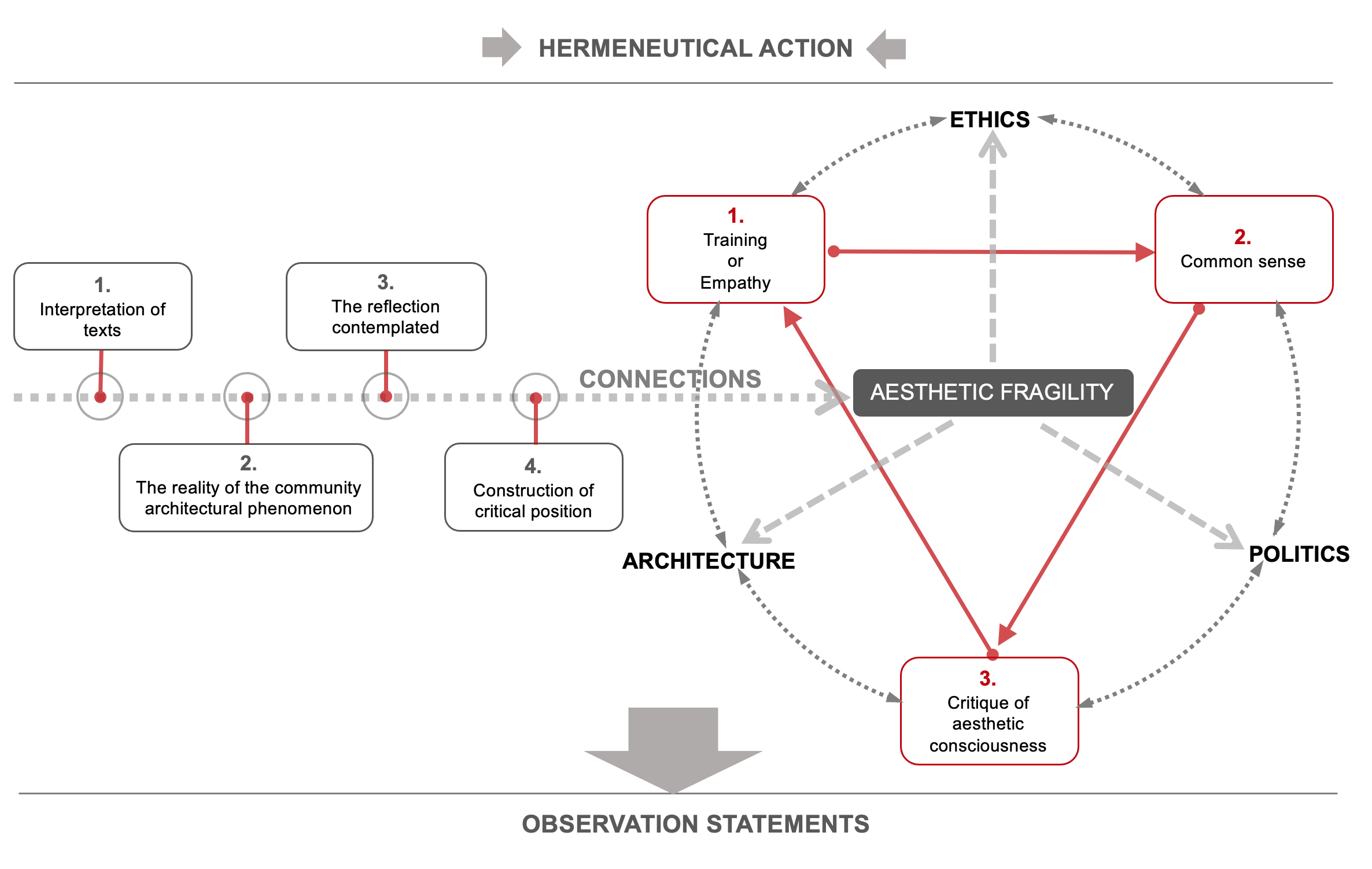

Given the need to think about the relational nature of architecture and its fragile condition, this article uses a descriptive hermeneutical methodology, in which intertextuality confronts various texts and authors that allowed in the first instance to establish three connections for reading the phenomenon of community architectures, which are: 1. The formation or empathy, 2. Common sense and 3. The critique of aesthetic consciousness, and in the second instance a narrative structure was built through the formal selection of exemplary projects and buildings whose architecture is community support space. So, the choice of collective and community equipment such as: schools, temples, community housing, cultural centers and memory center, evidence the hermeneutical process carried out from: 1. The interpretation of aesthetic aspirations through texts, 2. The reality that frames creative and collaborative developments that promote well-being, equity and human dignity from the actions of architecture, 3. The reflection contemplated from these contrasts and finally 4. The construction of the critical stance that manifests the interpretation, the recurrence of cyclic processes and the importance of the relationships between the parties and the totality (see figure 1).

Indeed, to give clarity to the methodological sequence it is necessary to decompose each of the constituent elements that resolve aesthetic fragility, in the first place the formation or empathy, is the culture that a community or individual has within its own historical and social context whose understanding is both ethical and aesthetic. It highlights the tectonic structure that contains the architectural work whose material support in relation to the context is within a mental process of symbolic consistency that recomposes the sphere of the usual life ethically. Secondly, common sense is the set of contents and interpretations on which a human group or collectivity and its will to act is founded, as opposed to the abstract generality of a universal reason. In this sense, the architectural work is a stratified complex that depends on the participatory intentional acts, understood as a correlation of statements and how these are reflected in the project within the temporal flow of experiences, and finally the critique of aesthetic consciousness, refers to architecture as an experience that produces a certain form of knowledge, which is the foundation of understanding and ability to judgment, since the architectural work is the harmonic conjunction that seeks to trace in the aesthetic properties, the potential that enables its concretion, not in the remembrance but in the active memory capable of connecting and building different emotions as parts of a single differentiated aesthetic experience.

This is why the connections of analysis identified ruptures and divergent paths between architecture and politics. In contrast to these two positions, the projects and works collected through the actions of the community, a historical-effect consciousness that is inserted in the particular history and culture that molds them is evident. So, the interpretation implies a fusion of horizons whose mission is to make visible the contradiction and discontinuity where the history of the project interacts with its own aesthetic background.

In short, in the study of the buildings presented in this article, each work is intimately interrelated and depends on the concept of operational analysis at a given time that presupposes complementary and paradoxical readings, as a necessary condition of criticism, this facilitates describing the general aspects of aesthetic fragility in the understanding of a new form of interpretation. Designate the reciprocity between architecture and politics, in which the intellect of aesthetic fragility moves, not focused on the immediacy of the reading and interpretation of the visual and apparent aspect of architecture, but in the knowledge of the aesthetic character. Likewise, through the analysis and comparison of their processes, they enrich each other and assemble applicable project strategies by making aware that the design process in these works is mainly based on the interpretation of multiple factors to which they should be responded in a pertinent and responsible way.

3. Results and discussion

Three observational statements are identified in the study as determinants of the results of the hermeneutical action.

3.1. From the transitory image to the global image

This section emphasizes the aspects of the representation of the architectural object, where it will be shown as architecture is perceived as a global image ignoring its local context, since in the contemporary panorama, projects with an established duration can extend their usefulness and roam in new spaces with updated programs that produce novel results. Even more paradigmatic, some projects and their works are carried out at the pace of the communities rather than according to the established schedules. Architectures that fight between the ethical and the aesthetic, where what is possible, adaptable, or manageable is outside the market protocols and official parameters.

Indeed, visualizing this panorama of the tension between the ephemeral and the enduring allows us to review architectures that adapt to various social needs with the least environmental impact and the greatest possible resilience. However, in figure 2 certain contemporary architectures acquire their value thanks to the immanence with which they interact where the presence of emblematic objects that are difficult to classify acts as inevitable references whose transitory appearance is identified with the globally architectural image.

Likewise, he great empires of history marked their territories with a specific architecture that, over time, has promoted the power and imposition of the western model of culture and science, moving us away from the meaning and sense of architecture; because now it is not experienced but copied. For Chomsky (2003), this discretion manifests when science only works to try to solve simple problems, which becomes descriptive, however, scientific analysis tells us about human problems and their relationships, this for him is a claim in other words, a technique of domination and exploitation.

Scientific laws, like current architecture, aggressively claim the territory of a globalized and dominant market economy, in which “a new smooth space is produced.” in which capital reaches its ‘absolute’ speed, based on machinic components, and no longer on the human component" (Deleuze & Guattari, 2012, p. 499). In effect, powerful image-making techniques seem to create a world of architectural fiction that neglects the existential basis and fundamental goals of the art of conceiving.

From this technocratic vision, the constructions are projected as a factor of development and apparent character of independence and object autonomy. In the words of Dominguez’s (2004) “[…] not to be seen in relation to, but to be used as true architectural voyeurs, […] of which unfortunately only the most superficial and merely geometric-compositional aesthetic aspects are used” (pp. 18-19). It is clear that we are facing a new era in which architecture should redefine its own meaning and its system of relationships. Castells (2005) perfectly describes the future of the new scenario where: “[…] the arrival of the space of flows is overshadowing the significant relationship between architecture and society” (p. 452). For this reason, this continued lack of historical and cultural contextuality inexorably leads to architecture towards a change of meaning that, in many cases, makes it design piece subject to the trends of itinerant foreign fashions; This is a transient image that aims to be global. Therefore, architecture must be located in the context of culture and its creations to think and promote a broad perspective, capable of finding a way out of the crossroads of reality.

3.2. Double identity and complementarity

The content of this section will show that architecture is used as a device to conceptualize contemporary conditions at the intersection between aesthetics and politics. In this sense, the production and commodification of architecture has relegated the concept of ‘image’ to a superficial form of representation and visual communication of social reality. However, in the field of architecture, spatial experiences are an inseparable part of the organization of people’s life and local identity in a global culture in many cases confused and deteriorated.

The architect’s influence on his peers’ lives is immense and long-term. See Figure 3, the primary school of Gando, designed by Diébédo Francis Kéré, where the architecture was thought based on the plurality of the inhabitants and their ideas, who share a quality of responsibility, have the knowledge and social purpose and base a contingency link. In this way, it involves the local inhabitants in the construction of the work, who combine political commitment, environmental efficiency, and aesthetic quality.

This interaction is able to consequently produce well-adjusted forms, even in the face of change. In the words of Toorn (2010) “[…] critical architecture opposes the normative and anonymous conditions of the production process and dedicated itself to the production of difference” (p. 297). Although the fit and mismatch between the form and the context trace a list of binary variables, which designate the reality of the facts and the possibility of carrying out a relevant architecture, there are new ways of living and feeling in which sensations and emotions merge humanism and materialism in people by seeing architecture as complementarity. It is valid to affirm that, a revealed knowledge whose indication leads to its own evolution, produces a natural architecture whose active system is functional, economical, efficient, aesthetic, and sustainable, capable of projecting the essential to take advantage of the multiple inherent possibilities.

3.3. Contemporary architectural fragility, the contradiction between ethics and aesthetics

In this fragment, the affinities between the action of thought and the processes of architecture are established, in which art as a means of representation and aesthetic expression transmits all kinds of sensations. Significant changes take place in architecture; according to Hegel “in its efforts to act towards the exterior and to represent the interior, art can lead to effects for which it uses the unpleasant, the forced, the colossal” (1981, p. 13); the author was interested in an unconventional topic for the time: how space could speak through the image, “nothing is more alien to the ideal style than the desire to please” (1981, p. 10). That pleasure that he manifests is generated by the impact of architecture, which leads him to think about how to do projects under the simplicity of feelings. Consequently, architecture builds the external material world at the same time that it builds the individual from his relationship with it.

What could a building symbolize? Furthermore, what does it mean for architecture and for people that this building exists? It is disturbing to see how relevance is given only to those buildings related to important events, “a building intended to reveal a general meaning has no other purpose than that revelation and for this reason it is a symbol” (Hegel, 1981, p. 41); Furthermore, despite the fact that the image of the past seems to be the precise evidence to understand the events, that information that is received can be interpreted in multiple ways, to the point of blinding humanity. However, “it has tried to develop a multidimensional thinking, opposed to Cartesianism and rationalist simplifications, which is based on the construction of systemic and relational interpretations, through linking and verification” (Montaner, 2002, p. 12). Therefore, it is pertinent to look for new alternatives where the real needs have possible solutions; that space in which the avant-garde concept of architecture is not only sustained by a transcendent design, but one in which it gradually adapts to the culture through a series of adjustments of the form to the community and that is the result of adaptation and gradual improvement over time.

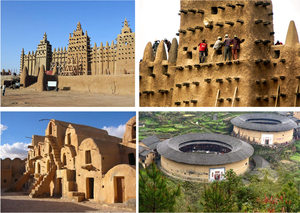

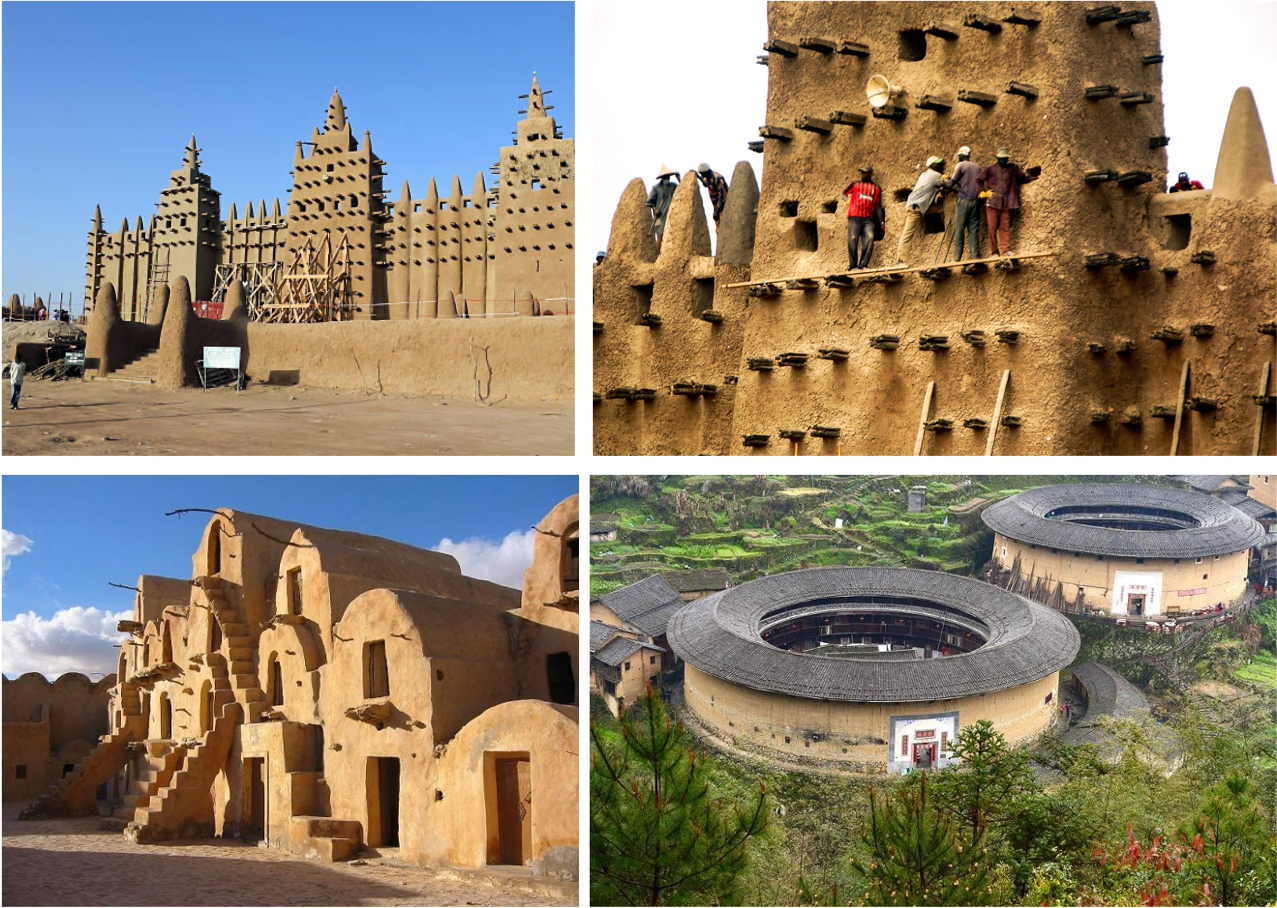

These transformations, projects, or prototypes should not be considered final designs, but as they are constantly changing, this makes them innovative. An example is the Great Mosque in the cubist landscape of the mud city of Djenné (Mali). It is the world’s largest mud building, rebuilt in 2005 by the Aga Khan Foundation on the ruins of an earlier temple probably dating back to the 13th century. It is all a matter of good design and maintenance; each year, the city is completely covered in mud, and the forms are rounded and rebuilt over time.

Even more, the so-called “troglodyte houses” in Matmata (Tunisia) and the tulou in China are shelters in the invisible field of architecture and society; only the display of appearance remains. Their spaces are no longer used for what they were intended. However, they continue to be part of the current time. These architectures testify to popular culture; they perpetuate materials and regional construction systems highly adapted to the environment. They constitute an enormous heritage that must be protected and conserved (Figure 4).

The building thus has a commitment to ethical function. If that commitment has brought a new freedom, it has also displayed a loss of place. The building can recover its ethical function only when it learns to preserve and articulate that tension. To do so, he first has to open himself up to the ambiguous language of space and place, as in Heidegger’s dream about The Black Forest Country House, expounded by Harries (1997) where he manifests as […] today the thought the very nature of architecture, as an expression of ‘the deepest interests of humanity’ […], is opposed to the spirit of the times, as the attribution of an ethical function to architecture (p. 356). Similarly, the aesthetic and political theme relates to the Cueva de Luz project (figure 5). This particular system is not born from architecture but from the genuine needs of its users. This community support space is located in the largest informal settlement in San José (Costa Rica). This project questions the limits of urban development, reflecting that citizen empowerment and the sum of public and private wills can go beyond the restrictions pre-established by development ‘codes’ that often contradict common sense and community aspirations.

The project has triggered a series of initiatives and collateral interventions that provoked urban regeneration from the root of human relations and active citizenship. A network of community referents, governmental and non-governmental organizations, and private companies that seek to improve the quality of the habitat through collective intelligence strategies as a design tool.

However, understanding reality makes it possible to legitimize the multiplicity of both ethical and aesthetic interpretations in the field of the creative process; In addition, it allows “[to do] a review of the elements that add value to architecture, such as ornamentation and the will to attend to social, cultural and ethnic diversity” (Montaner, 2007, p. 103). Architects, by materially organizing their relationship with the physical environment, can change architecture so that it has the potential to be deeply political. “His purpose remains to harmonize the material world with human life. Making architecture more human means making architecture better” (Aalto & Sust, 1982, p. 29). Thus, architectural constructions grant a horizon of judgment and aesthetic meaning to the world.

In the same way, in the Centro Memoria, Paz y Reconciliación project (figure 6), the ethical intention as an inherent desire for beauty and a better world is reconnected with the individual and sensitive values of aestheticization and architectural beauty. In the words of Pallasmaa (2014) “[…] both idealism and optimism, justice and hope are connected with the desire and passion for beauty”. (2014, p. 144). He affirms, therefore, that beauty coexists in the interaction between the ethical and aesthetic condition; For that same sensation, an exaltation is felt in the spirit that allows us to know the world and its evolution, “the role of architecture is not to embellish life, but to reinforce and reveal its essence, its beauty and its existential enigma” (Pallasmaa, 2014, p. 146).

In effect, the project is a memorial that makes visible the victims left by the internal armed conflict in Colombia and that highlights the values of respect for life, non-violence, truth, justice and reconciliation. A space endowed with material and symbolic atmospheres of meditation and silence, where the strategy is to build a threshold without barriers, a public, democratic and open space that establishes empathic relationships with users and exalts the unique conditions of the place. According to Harries (1993), this new way of seeing architecture as a transformative power seeks to provide the order and experiential meaning of a non-arbitrary thought of architecture, which we can call the ethical function of architecture.

Overall, the tension between the aesthetic and the political contributes to the reflection on how the manifestations of architecture determine certain fragile, ephemeral and lasting conditions, and how in the contemporary context architecture makes its own new democratic, social, cultural and environmental contexts; close to the great changes that define and characterize our time.

6. Conclusions

The aesthetic fragility allowed us to glimpse the way in which architecture promotes design processes and active participatory research, in addition to the ability to manage and validate agreements for the social construction of the habitat, by providing the framework for political action that implies fair distribution and equitable use of resources, especially where they are most needed. Additionally, from the descriptive hermeneutics in confrontation with the analysis of the studied projects, conscious research is established from the critical perspective that generates knowledge, alternatives and experiences by identifying significant problems to develop proposals that promote new, more equitable and accessible scenarios for all. Therefore, in the potential transformation of the creation of socially valued spaces and opportunities, these require constant collaborations and reciprocity between the users and the designer within pluralism in action. These interactions and understandings are necessary catalysts for imaginative and unexpected design proposals and solutions that demand the spatial character of the rights to understand them aesthetically in their meaning, identity and in their contradiction.